It has almost been a year since the tragedy. One October day last fall, many Missouri farmers were hard at work bringing in crops as the temperatures were quite hot for an autumn day.

In a soybean field near the town of Wooldridge in central Missouri, the bearings on one combine overheated and ignited a fire.

The 2022 harvest season was dry and windy — a problematic mix. Winds pushed the flames toward thick, dry vegetation surrounding the field. With every gust, the fire continued to move and engulf everything in its path, including the town.

Terrible day

Ultimately, nearly 3,500 acres burned, according to the Cooper County Fire Protection District. In the small community of Wooldridge, 25 buildings burned or were damaged. Still, firefighters saved the Wooldridge Baptist Church building, post office and the Wooldridge Community Club.

Cooper County Fire Protection District Assistant Chief Russell Schmidt told media that day that no one was killed, although several people were treated for burns. One person was taken to the hospital with injuries that were not life-threatening.

Today, this rural community is still struggling to recover, according to members of the Wooldridge Community Club. While much of the debris was removed from home lots, many have not started rebuilding.

As the potential for the same type of weather pattern sets up this fall in many regions across the country, farmers should stay vigilant around machinery — particularly combines — during harvest. It is a matter of protecting their equipment, crops, themselves and their neighbors.

When conditions like this are prevalent, what can a farmer do to mitigate the fire risk and still get the crop harvested? It may be impractical to stay out of the field completely on days when the winds are blowing and humidity is low, but many farmers last fall took those weather conditions into consideration.

Fire extinguishers and leaf blowers

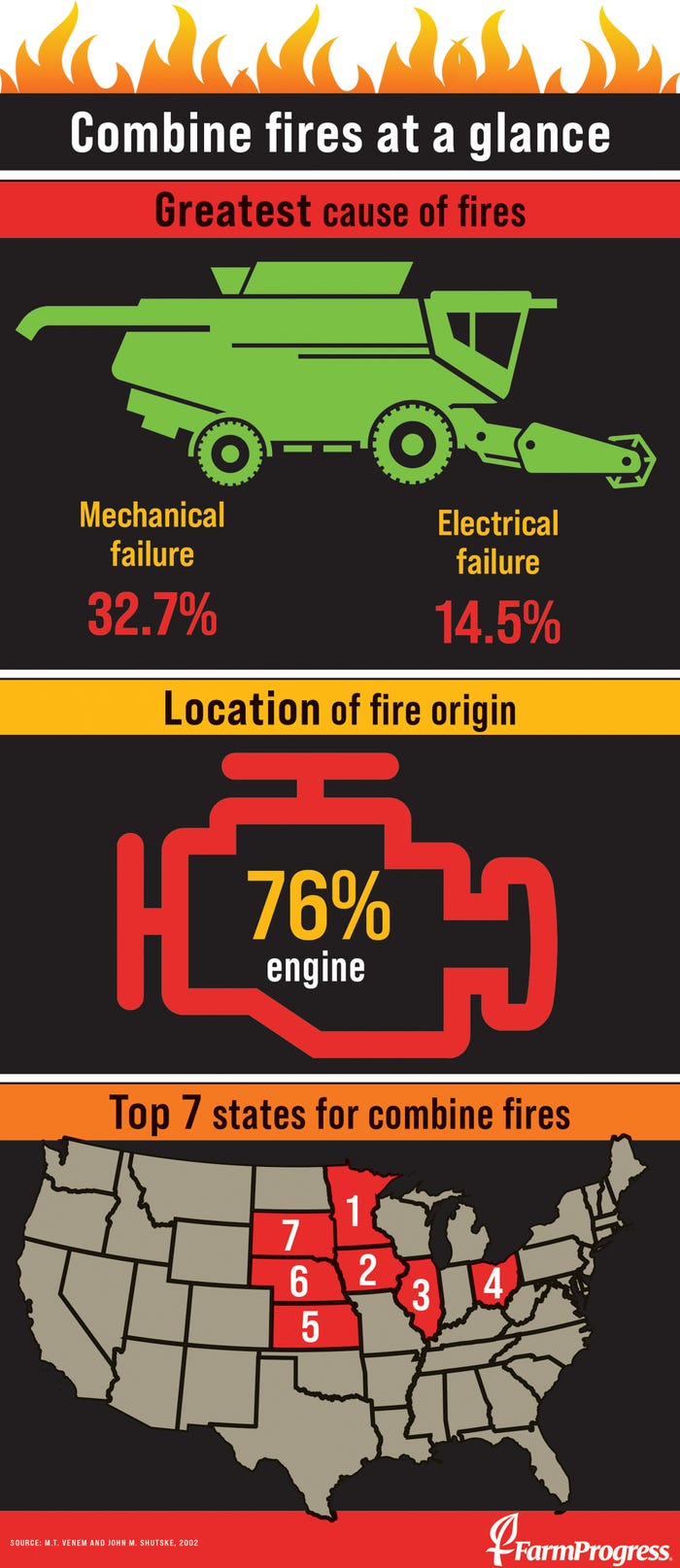

With more than 600 combine fires reported annually across the country, combines should always have regularly updated fire extinguishers on board during harvest season. That is a given.

One long range study looking at nearly 9,000 combine fires from 1984 through 2000 found that the engine area is by far the location of origin most often during combine fires. (See graphic.)

Fire prevention revolves around minimizing the risk of machines catching fire, so tragedies like Wooldridge are much less likely. North Dakota State University Extension experts have a few tips on how to prevent these fires from starting in the first place:

Keep it clean. Keeping a high standard of combine cleanliness is the best way to prevent fires, especially around the engine, turbo charger and exhaust system.

Exhaust components and turbo chargers can reach more than 1,000 degrees F, while surface temperatures can reach 900 degrees. With crop residue being able to ignite at 500 degrees and above, keeping combines clean is the single most important thing to keeping fires at bay.

Chaff and debris will build up on hot vehicle components while they are operated in fields.

These areas must be cleaned daily, which can be done with an air compressor or a leaf blower. The handy thing about a leaf blower is that it can easily be brought out to the field and kept in the cab for convenience.

Watch where you park it. Park vehicles in places with minimal vegetation as the hot exhaust could start a fire, as well as hot machinery parked on dry grass or vegetation.

Get repairs done. Be sure to repair any leaks or damaged pieces of machinery, including leaks in the fuel system, damaged electrical wiring, or worn-out exhaust systems.

Wait to refuel. Let machines cool off for at least 15 minutes before refueling, and never refuel while an engine is running.

Watch combustible crops. Crops such as sunflowers come with an especially high risk of fire as stems are reduced to a lightweight dust that can build up on the combine. Combine exhaust systems run at high enough temperatures to ignite the sunflower dust.

Chaff and dust can accumulate around bearings, belts and other moving parts, as well as underneath tractor and combine cabs. Dust and trash will become more and more combustible as they are let to dry.

Power wash it. Consider power washing equipment to remove grease and oil, which can allow a fire to spread rapidly. Removing this excess grease and oil can aid in improving machine efficiency while keeping equipment cool.

In case of fire. If a fire does break out, turn off the machinery and exit immediately. Call 911 or emergency services before trying to extinguish it yourself. Keep two fire extinguishers on the combine, one in the cab and one that can be accessed from the ground. A fire extinguisher should also be found in grain hauling equipment.

What about insurance?

During last year’s flurry of wildfires and crop fires during harvest season in his area of northeast Nebraska, Ryan Loecker, location manager for Town and Country Insurance and north region leader, GTA Insurance Group, worked with farmer clients who were affected.

“My first recommendation would be to go in and talk with your insurance agent and make sure you carry the proper coverage in case of a combine or harvest fire,” he says.

NOW WHAT? Once a combine fire has occurred and the combine and crop are burned, what are the implications financially for a farmer? This depends on the origin of the fire and insurance coverage on the combine and the crop.

“In the case of a fire, your combine would be covered under your regular farm property insurance. So would the headers,” Loecker adds. “But the weird thing is that under your regular crop insurance, which covers drought, wind, flood and hail, the crop that would be destroyed around a combine would not be covered if the fire was caused by the combine. If the fire was caused naturally by lightning, for instance, and it started in a neighboring CRP tract and then spread into your crop field, that would be covered, but a fire that comes from equipment is not.”

However, Loecker says that if you carry hail insurance on your crops, then fire caused by any source, including a combine, would be covered for your burned crop acres under those circumstances.

An insurance example

“As an example, let’s say you are out combining in your own field, and the combine starts on fire and burns up 5 acres of the field,” Loecker says. “Because it is not naturally occurring, the burned acres would not be covered. If you hired someone to custom combine, and their combine started on fire and burned some of your crops, their liability insurance would probably pick that up.”

The farm blanket insurance can also be useful in these cases. “In many cases, combines have toolboxes these days with thousands of dollars of tools; and in the cab, there may be add on equipment like GPS, yield monitors and other technology that could be covered under the farm blanket,” Loecker says.

While fires are a part of farming, preventing those fires in the combine takes vigilance from producers in making sure their harvest machinery is clean and free of debris and residue that could ignite.

Beyond that, make sure you have a conversation with your insurance agent to tailor the coverage of your equipment, crops and property to your needs and risks.

Read more about:

Farm SafetyAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like