At a Glance

- Extreme rainfall is more frequent today, and on bare ground, more nitrogen and phosphorus run off.

- The levels of phosphorus in surface water increase substantially with increased precipitation.

- A 5% increase in cover crops in a watershed essentially mitigates one day of extreme rainfall.

Farmers well know that when rain falls hard and heavy, as it often does these days, it’s not ideal. Heavy rains mean water is running off, and water running off can take soil — and nutrients — with it.

How much are you losing and after how big of a rain? That’s what University of Illinois researchers Marin Skidmore and Jonathan Coppess set out to learn recently.

“We wanted to ask what happens right around a precipitation event, and how does water quality vary based on activity on the ground?” Skidmore says.

What they learned was that extreme weather events impact nutrient loss, and that while farmers can’t change the weather, they can minimize the loss with their own practices. Or in other words: Farmers cannot control extreme events, but they do have some control over whether excess nutrients are present on bare or frozen soils — and can then be washed away.

“When you look at the different flow or the different ways in which these nutrients move, you see how the farmer’s decisions can make a difference,” Coppess adds.

The details

Skidmore looked at previous research from Wisconsin and learned that half of all nutrient runoff came from precipitation (either rain or snow) in February and March when the ground was frozen, even though that precipitation made up just 11% of annual precipitation. On nonfrozen ground, the highest runoff occurred in May and June, when more high-intensity or repetitive rainfalls led to higher soil moisture.

The common denominator in both time periods is that crop covers were minimal.

“When we see a 5% increase in cover crops in a watershed, that essentially mitigates one day of extreme rainfall,” she says.

Skidmore says not all runoff creates the same nutrient losses. Runoff from frozen ground means less soil is lost, which means the nutrients being lost were sitting on the soil surface. Runoff in May and June erodes more soil and carries what she calls “legacy nutrients,” which may have been applied decades ago and are bound to the soil.

“The legacy nutrients — especially phosphorus of decades past — is something farmers of today are up against,” Skidmore says. She explains that phosphorus moves through its cycle (and our ecosystems) slowly, which means P that’s bound to soil could remain there for a century. Plants feed on phosphorus in the soils, but only small amounts dissolve and are available to plants, leading to yield limitations.

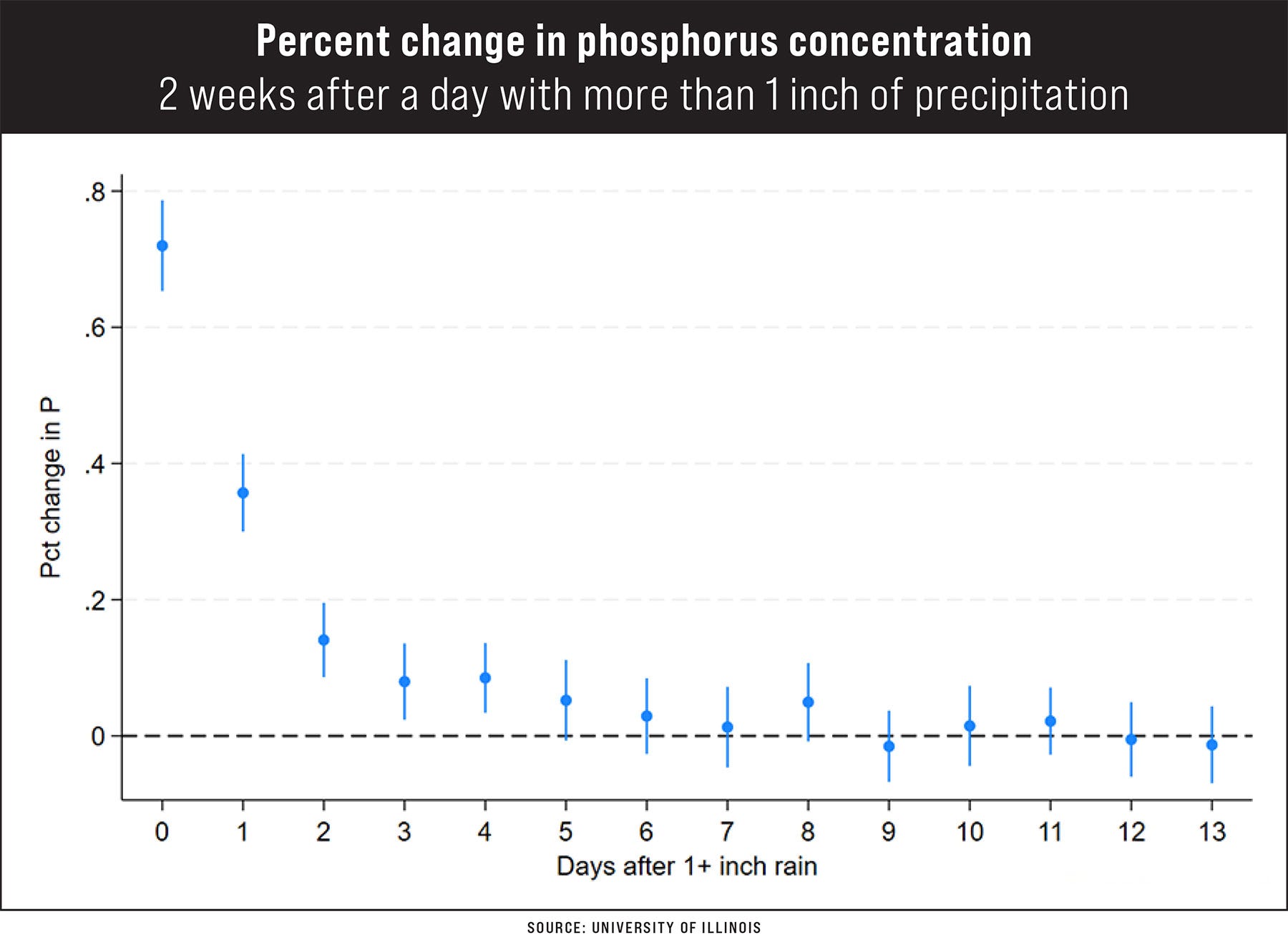

While phosphorus moves through the system slowly, Skidmore’s research shows its runoff spikes around extreme precipitation events.

“The combination of legacy nutrients and extreme weather is very likely part of what we’re seeing in these less-promising NLRS results,” she adds.

The levels of phosphorus in surface water increase substantially with increased precipitation.

Rain on frozen or bare ground leads to runoff, especially when fertilizer was applied following harvest. That creates perfect conditions for nutrient loss directly into nearby streams.

But what about the big, extreme rainfalls? Skidmore cites previous work finding that so-called 10-year rain events generate runoff 66% of the time. The 25-year rain events generate runoff 82% of the time. Undoubtedly, those rains are eroding soil, too, and soil erosion compounds the fertilizer loss problem.

Skidmore points to a study showing U.S. corn growers spend half a billion dollars a year on fertilizer to make up for soil loss. North Dakota State University research estimates 1 inch of lost topsoil costs $688 per acre in lost nutrients.

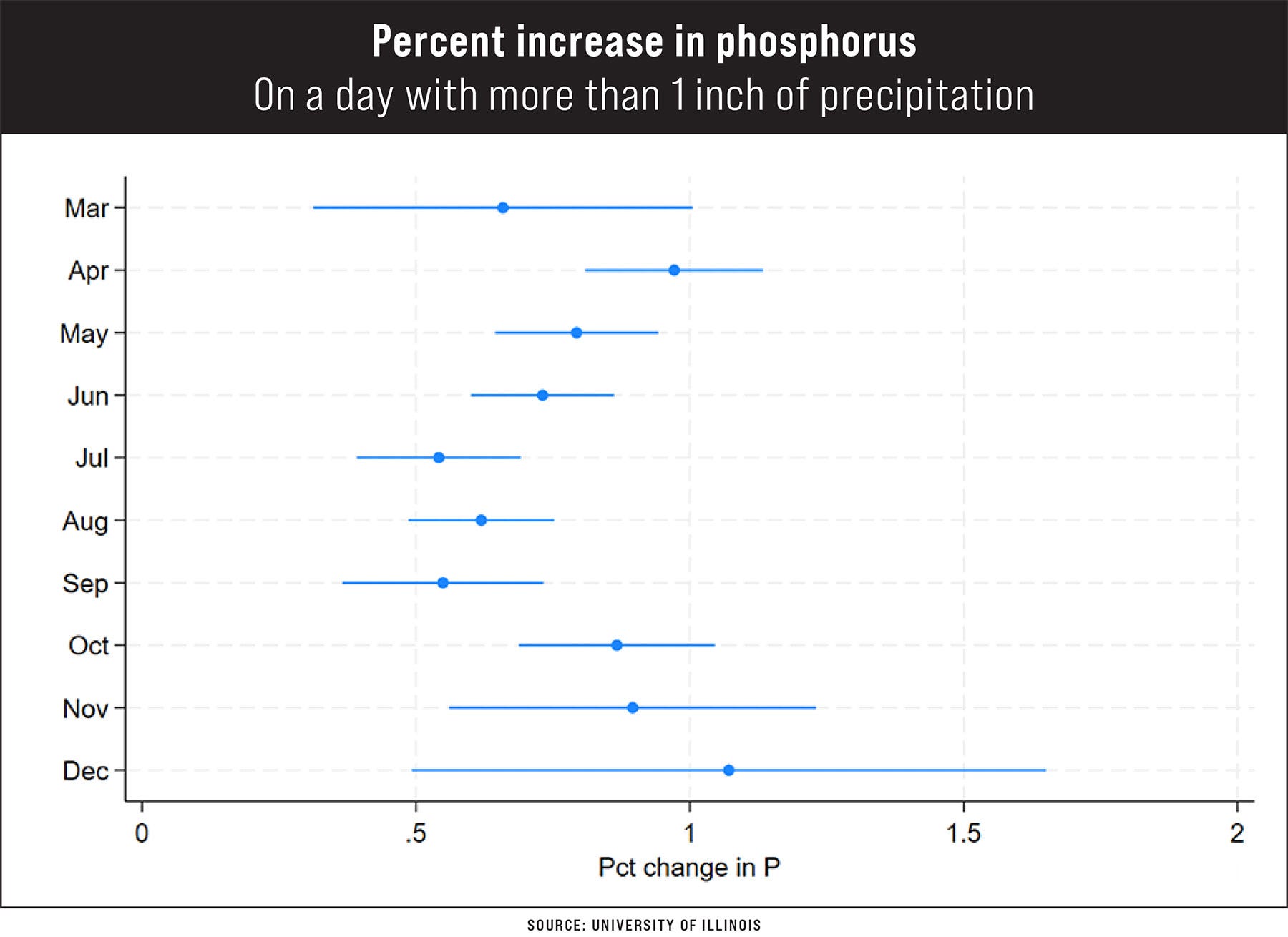

This shows the percent increase in phosphorus in all surface water readings on a day with more than an inch of precipitation, compared to one with less than an inch based on the month the rain fell. While phosphorus increases by 50% in response to an inch of rainfall in summer months, it nearly doubles in winter and spring.

Peak conditions?

The big takeaway: Soil conditions matter when rain falls.

Rain or snow on bare ground is a recipe for higher runoff, higher soil losses and more soil movement. And if farmers and landowners continue as they are today, increased extreme precipitation will result in more phosphorus in water sources.

“In contrast, healthy soils — especially those soils protected by a cover crop — are less vulnerable to heavy losses observed around extreme precipitation events,” Skidmore explains. Cover crops, conservation tillage and buffer strips make land more resilient to extreme weather and help farmers to manage production and reduce runoff.

The bottom line? Farmers can’t control the weather or the big rains, which are likely to get more extreme over time as weather patterns continue to change. But farmers can decrease the amount of nutrients sitting on bare or frozen soils before the rain or snow arrives.

Read more about their research on Farmdoc in Part 1 and Part 2.

Policy and conservation

Coppess has deep experience in federal policymaking and says the U.S. needs to get serious about investing in conservation — and especially in the kind of conservation that would make a difference.

“Part of my frustration is that we throw small amounts of money at conservation and expect major miracles to happen,” he says. Instead, he notes, policymakers fight over a reference price increase, which has no benefit or value to conservation.

“A few hundred million dollars a year in EQIP isn’t going to cut it anywhere, let alone in a major state,” Coppess says. As part of this project, he spent time studying why nitrogen moves so fast in water versus phosphorus over land, and became further frustrated with policy.

“We’re not working on some of these very difficult scientific questions of how these nutrients work and flow,” he says, adding that additional investments via the Inflation Reduction Act have helped elevate the conservation conversation.

“But the dysfunction we’re seeing in Congress makes it really hard to dive into this kind of specificity,” Coppess says. He says there’s a way to rethink conservation policies to be more cost effective. “Policymakers design crop insurance policy according to risk factors that farmers face, but they don’t look at risks and price environment on conservation.”

His big takeaway? Research like this should cause policymakers to get serious about how to keep nutrients in place.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like