“The market is always right” is a mantra championed by grain traders. Never mind that the trader credited with the saying squandered several fortunes, went bankrupt and killed himself toward the end of the Great Depression.

But what if the market was right and USDA is wrong about corn supply and demand headed into harvest? The government’s latest forecast may overstate potential for burdensome supplies and near-record production, according to evidence from cash and futures prices.

Of course, the market could still change its mind, with only 9% of the crop harvested a week ago. And basis weakened with wider carries in the in the past week as more corn came in. But barring dramatic news the next few weeks, prices say corn stocks aren’t nearly as plentiful as shown in the Sept. 12 World Agricultural Supply And Demand Estimates.

Average Midwest cash corn prices and futures spreads are both significantly stronger than indicated by key variables affecting basis levels historically. Though this doesn’t mean a bull market looms in the months ahead, it suggests surprises could be in store for those who don’t respect the wisdom of markets – or put too much store in them.

Basis and spreads are key factors influencing storage decisions – and the clock is ticking for farmers to pick their strategies.

Storage strategy impacts

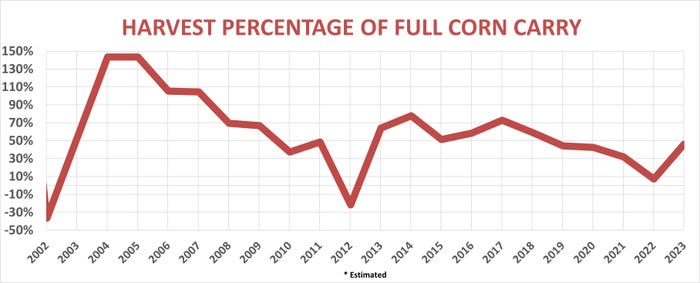

Now, both basis and carry in spreads between December and July delivery are certainly different than in 2022, when disappointing production and the lingering post-pandemic surge in commodity prices sent futures soaring past $8 a bushel. December-July carry is running about at the 20-year average. But it’s still below levels from 2016-2018, when stocks were as high as USDA forecast Sept. 12 for the 2023 crop and basis was weaker too.

A strong cash market at harvest compared to futures can affect options alternatives and make selling crops off the combine more appealing, either outright or with a basis contract for deferred delivery. Less carry in spreads between harvest delivery futures and deferred positions can make storage hedges less attractive for those interested selling the board to capture basis appreciation in the months ahead.

To study what the market may or may not be saying this year, I looked at how eight variables are associated with both futures carry between December after harvest and July the following summer and basis in eight key Midwest states. Not all of these variables appear to have the same influence at all locations, compounding the difficulty making any blanket forecasts about what the market is saying, about USDA’s forecasts or anything else. But when mashed up into a multiple regression analysis, current readings for factors influencing basis and carry historically indicate basis should be significantly weaker than it is, despite recent weakness, with carries much larger as well.

Are bins full?

Weak basis and large carries tend to go hand-in-hand. Both can be incentives to hold grain off the market at harvest. Farmers don’t sell as much when cash prices flounder compared to futures, while commercial interests like elevators may see more incentive to hedge and hold inventories when carries are larger.

So what are current markets saying? Basis at the eight locations studied came in around 30 cents under December futures, just about average, but 20 cents stronger than forecast by key variables.

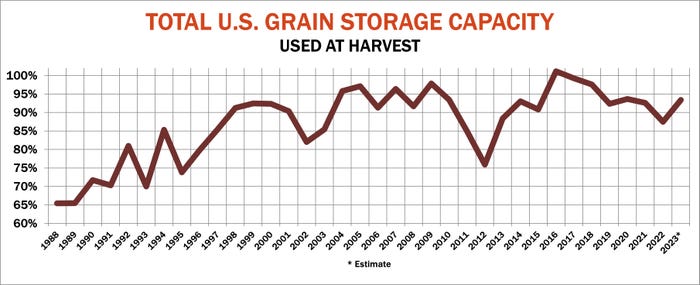

The factors with the strongest influence relate directly to supplies: how yields compare to normal and the percentage of storage capacity used by new crop production and supplies already on hand Sept. 1. Adequate yields give end users less urgency to buy at harvest to lock in needs, which weakens basis. Farmers and elevators are also more likely to move grain if they don’t have room to store and keep it in condition, hurting cash prices too.

The Sept. 12 WASDE cut expected corn yields but increased harvested acreage, increasing production to 15.134 billion bushels, less than 1% below the record set in 2016. Estimated yields were 3% below the statistical trend, nowhere close to a disaster, and above the 10-year average. Together with other crops it means around 93% of storage capacity could be used soon.

A year ago, 85% of storage was full, and harvest basis averaged 4 under at the eight locations, the strongest since the 2012 drought year.

The WASDE forecast leftover supplies at the end of the marketing year Aug. 31, 2024 at 2.221 billion bushels, a burdensome 56-day supply at expected usage. This variable also tends to depress basis and widen carries, as does the comfortable amount of old crop 2022-23 corn available.

Storage costs swell

In addition to supply, costs for interest and transportation also influence basis and carry, though in smaller and more variable ways around the Midwest.

The cost of moving corn can be a double-edged sword, depending on the mode, location and year. The price of highway diesel tends to be associated with stronger basis and tighter carries. While expensive fuel increases costs, end users are more willing to pay for the freight by bidding up cash prices to lure grain out of storage when crops are smaller and supplies scarce. Buyers let sellers – farmers – foot the bill when there’s plenty of corn around to purchase.

Diesel of course also powers tugboats and locomotives, but higher prices tend to be associated with weaker basis – some places.

Fuel is only one cost involved with shipping corn down river. Barges cost more when demand is stronger. It isn’t this year, but barges are in short supply due to low water levels that decrease tow capacity, forcing shippers to use shorter tows with less in them.

Stronger barge freight rates have a bigger impact on river markets adjacent to the Mississippi like Minneapolis, Illinois and Iowa, but wield less influence away from the waterway, like Kansas, Ohio and Nebraska.

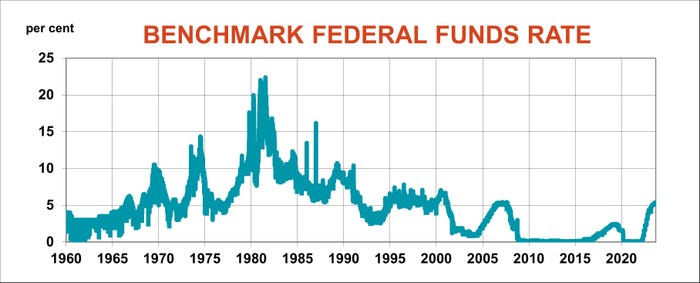

Higher interest rates increase the cost of holding grain and not selling it to use the proceeds to pay down debt or invest at the bank. The Federal Reserve last week confirmed borrowing costs are likely to stay high, keeping its benchmark short-term rate 5.25% higher than when the credit tightening cycle began in response to a spike in inflation.

But the cost of money also cuts both ways. Overall, higher interest rates bring weaker basis because buyers transfer the expense to sellers. That seems true in Iowa and Ohio, but not in Missouri or Nebraska.

Markets defy shutdown

So what do the numbers mean?

Maybe nothing. All forecasts have room for error and taken individually the error possible with each variable is relatively large. Still, taken together the eight factors account for 94% of the variance in basis.

So, the numbers maybe mean a lot. The market appears to be hinting that USDA’s forecast for large supplies and perhaps tepid demand is overstated, at the least.

The government, could, of course, cut its supply and forecasts by the time harvest reaches the halfway point. But just when any changes might be forthcoming remains in doubt, with mounting worries about a government shutdown that would halt USDA reports.

Even if the lights go off at USDA, markets will stay open, giving the market time to catch up with the government’s bearish supply and demand outlook. Watch futures carries and basis in cash markets you monitor for signs of a shift in the market mood. Weaker cash prices and wider carries could mean the market’s mood about corn is turning bearish too.

Knorr writes from Chicago, Ill. Email him at [email protected]

The opinions of the author are not necessarily those of Farm Futures or Farm Progress.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like