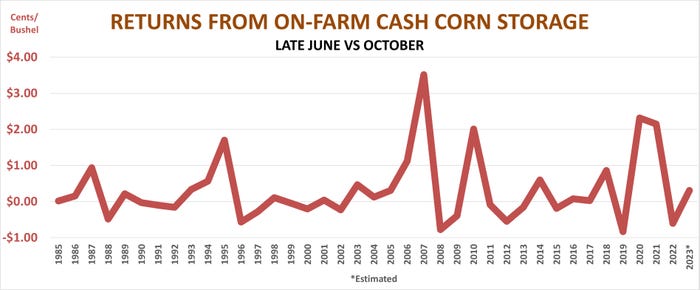

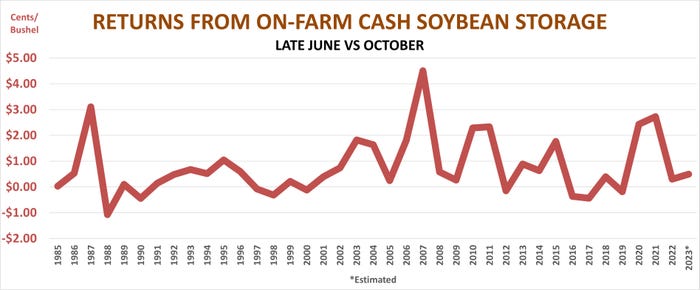

Growers storing last year’s corn and soybean harvests into early summer mostly lost money compared to what they could have earned selling off the combine. That was true for all of the corn strategies vetted in Farm Futures annual storage study, and most of the soybean tools too.

But past performance of key indicators suggests potential for storage to pay dividends on 2023 crops, whether they’re put in the bin or sold at harvest and replaced with futures or options contracts. Still, earnings could be lower than long-term averages, with soybeans facing more headwinds than corn.

Based on current data, putting crops in on-farm storage until July 2024 options expire at the end of June looks ready to be the top performing strategy for both corn and soybeans. That’s perhaps not surprising, because on-farm storage leads our study historically.

If the past is an indication, corn profits compared to harvest would run around 31 cents a bushel, just three cents below the long-term average, with all nine strategies studied netting gains.

Soybeans would earn 50 cents a bushel on farm, good but below the average return, which topped 80 cents from 1985 through 2022, the years covered by the Farm Futures study.

No free lunch

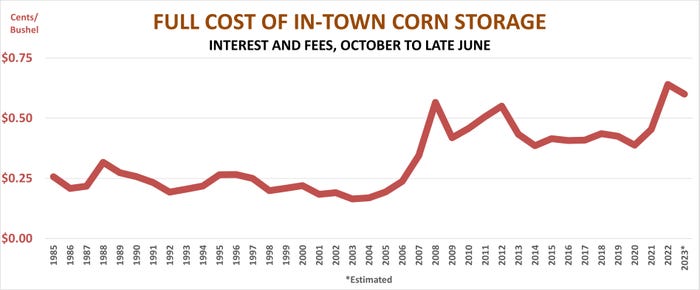

Of course, making money storing crops is easy – if prices keep rising enough after harvest lows are confirmed. But higher prices alone don’t guarantee gains, because storage brings costs. Even if bins are paid for and fully depreciated, prudent accounting requires charges for interest, either because harvest proceeds aren’t used to pay off loans or invested.

Handling charges also accrue for moving grain and keeping it in condition. Using commercial storage adds fees paid to elevators, which also vary, along with drying costs, if any.

Incorporating futures and options brings commissions paid to brokers, as well as premiums for puts or calls, which must be paid upfront and are recouped only if markets trade in your favor. In other words, there’s no such thing as a free lunch when it comes to storage.

Tracking these costs and other factors into harvest can offer clues about potential from different strategies. But even the variables with the strongest correlations to profits account for only a third of the variance in returns historically, leaving plenty room for chance to determine the outcome of your storage decision. Markets are as unpredictable as ever, particularly after years of financial crisis, trade wars, a pandemic and political chaos, both in the U.S. and around the world.

So, here’s what to watch and what it could mean for storage potential.

Starting point

To be sure, with 2023 crops still ripening out in the field, predictions could change if yields come in vastly different than USDA reported Aug. 11 in its first survey of farmers and their fields. Demand in the months ahead could also be important, especially if the government’s estimates for supplies at the end of the 2023 crop marketing year Aug. 31, 2024 are significantly higher or lower.

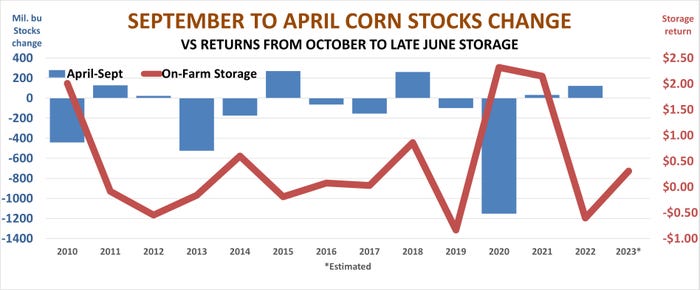

Indeed, changes in ending stocks of corn from September before harvest through April the following spring show the highest correlation to storage results of the variables studied. That makes sense, because they’re also the hardest to predict.

Performance of 2020 crops shows how a dramatic reduction in in USDA’s inventory forecasts can have a big impact on prices. The government slashed 1.15 billion bushels off its September 2020 corn estimate by April 2021, due to sharply lower yields and a decline in harvested acreage, fueling a rally that helped nearby futures gain nearly $3 while surging past $7.

But even if stocks estimates stay unchanged, storing corn on farm look profitable, though projected earnings of 24 cents a bushel would be less than the long-term average. Under this scenario stronger futures and basis would help cash storage, Other strategies could benefit as well, including selling out of the field and buying futures and hedging the inventory with July futures to profit from basis gains. Futures gains don’t look strong enough to pay for the cost of buying call options as a surrogate for corn sold off the combine; buying near- and out-of-the money calls wouldn’t earn back all their premiums, according to this model.

Follow the money

Reductions in soybean ending stocks over the first half of the marketing year aren’t quite as important statistically for gains from storing that crop. Still, even steady soybean carryout forecasts from September 2023 to April 2024 could translate into storage profits of 88 cents a bushel, eight cents higher than the long-term average.

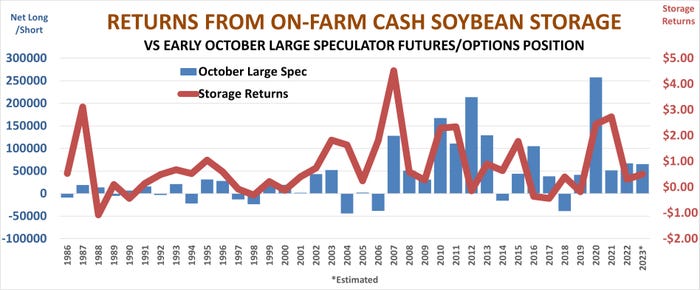

Another variable could be more important for cash soybean storage, and also factor into corn profits: Money flow. Futures and options positions held by large fund speculators could tip which way the smart money is moving. If the funds are already buying at harvest, it may be time to get on the train. The larger the net long positions held by funds during the first week of October, the stronger odds are for gains from holding both corn and soybeans on farm. The latest data from the CFTC translates to corn gains at 30 cents, with soybeans netting 50 cents.

Harvest markets may provide more clues about momentum. Higher average cash prices off the combine compared to the previous year are also correlated to storage gains. Markets moving higher tend to keep moving higher – until they don’t.

Carry and basis

Another viable related to cash prices could also be significant: basis, in this case the difference between deferred July futures and cash markets at harvest. This represents the combination of nearby harvest basis and carry from harvest contracts to July delivery.

Currently, both corn and soybean futures have carries – July contracts sell at a premium to December corn or November soybeans. If cash markets for corn and soybeans show typical harvest weakness, the difference between nearby cash and July futures could be fairly large, say around 60 cents a bushel, giving cash storage a chance at profits in both.

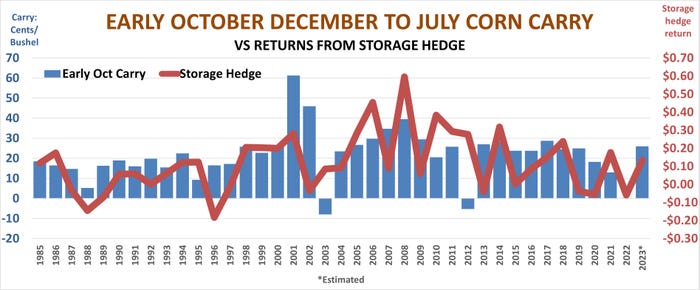

But where this carry really could pay dividends is for growers storing crops for basis appreciation by hedging inventories with either futures or by buying put options. Wide carries between cash and July futures give storage hedges a chance to earn about average returns for both corn and soybeans.

Also compare futures carries to the full cost of holding these crops; the higher the percentage of full carry in futures spreads, the higher the likelihood storage hedges will pay off.

Selling futures to protect inventory limits gains to basis appreciation. Buying puts leaves the upside open – once premiums are covered.

“Puts” for the bin?

Using puts to protect inventory from falling markets isn’t a cheap strategy. In addition to paying put premiums and commissions up front, growers also face other costs for grain held on farm from handling and interest. As a result, average gains are not as big as from storing unhedged, but the protection helps the strategy pay off more often than not.

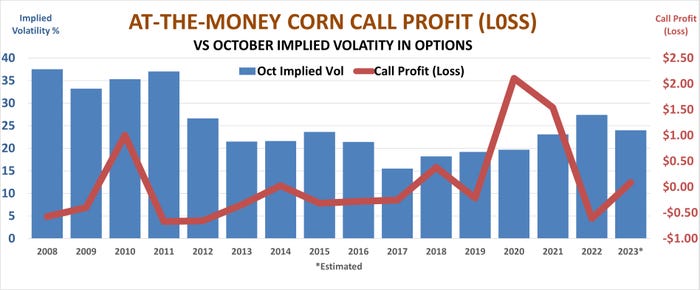

A key option statistic may also provide guidance for those thinking about selling off the combine and keeping a leg in the market by buying call options. Implied volatility measures traders’ current opinions about potential for large market moves – the higher the volatility implied by options premiums, the greater the potential for swings.

Implied volatility tends to be weaker at harvest, when yields are better known, than during the peak of the growing season, when weather can wreak havoc on production. When it’s higher at harvest, call option premiums tend to be higher as well. That appears to depress potential for the calls to pay off, leading to lower returns. Current volatilities are already weaker than typically seen at harvest, which could make calls more affordable if the trend continues.

Knorr writes from Chicago, Ill. Email him at [email protected]

The opinions of the author are not necessarily those of Farm Futures or Farm Progress.

Read more about:

Grain StorageAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like