Corn harvest is halfway done. Along with lower-than-expected yields nationwide, that’s helping support prices and increasing the odds the market has reached a seasonal bottom.

Indeed, hope springs eternal. But as on-farm grain bins fill, growers running out of space face a conundrum – how best to take advantage of potential rallies into winter, or perhaps spring and summer.

With interest costs running around 3.5 cents a month, even assuming corn is put under loan, and storage charges at elevators that much or more, holding corn in town could run at least 55 to 70 cents until June. Current basis and futures carry from December to July put together slipped toward the bottom of that range on last week’s rally. That might be enough to pay for commercial storage – unless cash prices or futures combine to thwart basis appreciation, wiping out any return.

Those costs and associated risks raise the question of whether to just sell corn now instead, and replace it with “paper,” using futures and options strategies as a surrogate for elevator storage. But there’s no perfect solution because each of the myriad alternatives comes with risks and potential rewards.

So here are three strategies to consider, and their performance historically. As always, before trying to use “paper,” be sure to understand not only how the tool works, but also what the downside could be in a volatile year that’s already been full of surprises. As the saying goes: Buyer beware!

The call option answer

Call options convey the right, but not the obligation, to buy futures for a fixed strike price in exchange for a premium paid in full upfront. Since these contracts began trading again in the mid-1980s after a decades-long ban, buying calls to replace corn sold out of the field became one of the first ways many farmers started using the contracts.

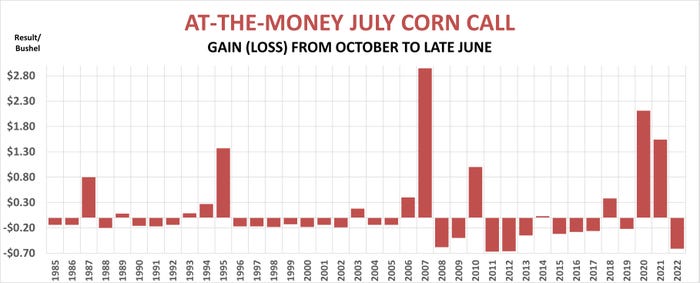

The idea sounds simple enough. If futures rise, the call could gain in value and be sold for a profit added to proceeds from cash grain sales. Calls bought in October 2020 and 2021 returned handsome profits of $2.11 and $1.54 a bushel, while returns approached $3 in 2007-2008.

In practice, buying calls doesn’t always work. From 1985 through 2022 the strategy made money around a third of the time, netting around 12 cents a bushel on average, according to a Farm Futures long-term study.

One problem? Some years futures fall or trade flat, making the option worth little or nothing.

In addition, more than futures prices influence the cost of a call. So, even if the market goes up, the option’s value could still erode.

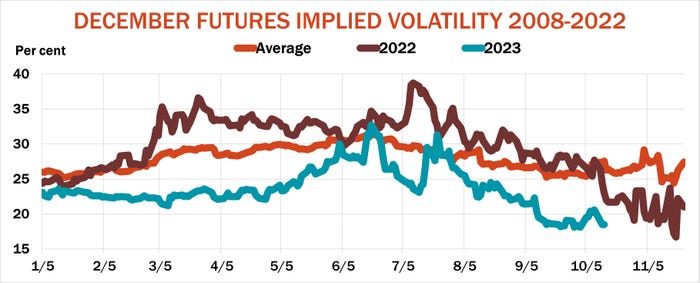

In nervous markets, for example, uncertain buyers may be willing to spend more for options protection. This factor is known as implied volatility. The chart above illustrates how this influence tends to rise during the peak of the growing season around the window for pollination when uncertainty about yields tends to peak. Once the crop is made, volatility subsides, falling into harvest as results come in off the combine. But volatility can also be higher at harvest if traders fear falling prices.

This year, volatility is bottoming right on its normal timetable. Though the chart shows December options, which expire around Thanksgiving, the same trend is true for contracts on futures delivered later in the market year. The Farm Futures storage strategies study uses options on July futures, which expire toward late June – about the same duration as a CCC loan for those who buy them during harvest.

Options on deferred futures usually cost more than those on the nearby contract because they have longer to run. In a normal year, the implied volatility for July options also tends to be a little higher than for December options in October. July “at the money” calls conveying the right to buy futures for the futures price when they’re purchased at harvest typically run around 35 cents a bushel – about where they traded last week.

“At the money” calls have no, or very little, “intrinsic” value. That is, they can’t be exercised immediately at a profit. Instead, their cost is from how long they have until expiration. This factor, known as time value, acts as an anchor. Even if prices rise, they must rise enough to offset the decay in value the option loses over time.

Interest rates, to a lesser degree, also affect options values but have a much bigger impact on cash grain storage profitability. So, interest and commercial storage fees usually cost more than a call, making the options seem like a good solution. Unlike storage in town where losses can be huge, the worst that happens with a call is losing all its value if held to the bitter end until expiration. Still, those losses topped 60 cents a bushel on last year’s crop.

Covered calls

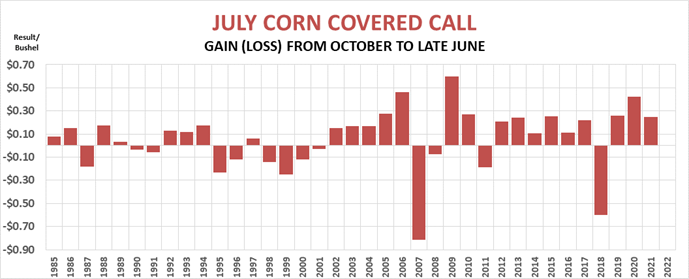

If the cost of calls can be dear, there is a way to take advantage of their price. Those who “write,” or sell the contracts, earn the premium in return.

Selling a call of course has its own risk. If futures rally more than the premium earned plus commissions, the net position is a loss, and the red ink theoretically is unlimited. That’s one reason selling “naked” calls usually is best left to speculators.

This practice does have applications for farmers. Selling calls to “cover” grain in storage or out in the field provides some downside protection if prices fall – the premium earned. But gains from futures rallies are capped by the strike price of the call sold.

Farmers selling cash grain can also sell covered calls by buying futures. This works best in markets that trade flat or don’t fall sharply, though the option also limits gains from the futures position if prices rise. Losses can mount if futures fall more than the premium earned.

In 2008 the strategy lost 81.75 cents a bushel. Though selling an at-the-money call earned 58 cents in premium, futures tumbled $1.39 after harvest as the Great Financial Crisis took hold, creating a large paper loss. Buyer beware indeed!

Bull spread

These options strategies replace grain sold on the cash market, which fixes the basis on those bushels. So, one drawback to “paper” is that it doesn’t capture any post-sale gains in basis. Some years, those gains can be a significant benefit to those still holding crops.

A third strategy doesn’t use options at all. And in some cases, it also benefits from basis appreciation. That can generate gains when cash rallies, but futures don’t follow, foiling call options profits.

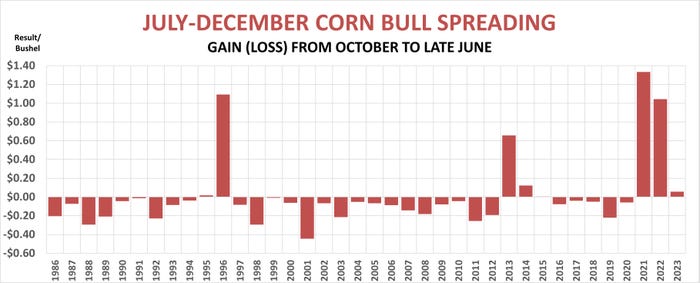

This technique uses futures, but not in a straight long position. Instead, a spread is created by buying old crop futures, in this case July, and selling new crop December for the following fall. This is known as a bull spread, which increases in value when the old crop futures bought rise faster than the deferred contract sold.

Good years from bull spreading aren’t frequent – just 21% of crops from 1985 through 2022, with the rest generating losses. By contrast, buying call options profited 34% and covered calls 63% of the years. So why even consider a spread?

Think about the triggers for post-harvest rallies. Some years, the market gains because old crop supplies tighten. End users become nervous about fulfilling needs, and they buy old crop futures as a surrogate.

That’s what happened after the 1995 crop. Despite extreme summer heat that slashed yields, exports surged, leaving just an 18-day supply of corn on hand by the end of the marketing year – the tightest on record. Led by the July 1996 contract, nearby futures surged to the highest level ever at that time, driven in part by farmers forced to buy their way out of positions during the infamous hedge-to-arrive debacle that put some in bankruptcy.

December didn’t follow suit because traders expected production to recover. As a result, buying July 1996 and selling December 1996 at harvest netted $1.0925, nearly as much as the $1.39 made by buying the July at-the-money call. Bull speading also worked well after the 2020 harvest, thanks to exports that reached all-time highs, though again, it earned less than buying a call outright.

Which is best?

Each of these strategies has its share of pros and cons. Bull spreading on average earned just a penny a bushel from 1985-2022, but it also lost the least, 44.5 cents. Buying calls netted the most on average, around 12 cents a bushel, but lost up to 67 cents. Covered calls faced the biggest loss, more than 80 cents, and earned on average around 6 cents. But the strategy made money 63% of the years.

Choosing which if any alternative to consider takes a good crystal ball, and those are hard to come by. No one knows, of course, what will happen in coming months, but we do know a few things about this year’s environment.

Old crop stocks are projected as large as in 2016 through 2018, years with losses from bull spreading because old crop wasn’t in short supply. Buying calls earned profits only one of those years, while covered calls posted gains in all three.

The biggest risk to all three strategies is a corn market that turns south. A return to $4 corn would be especially painful for covered calls, which face the most downside risk historically.

So, there’s no perfect solution. As always, it’s a matter of balancing risk and reward – or just taking a profit if you can get it, and moving on to 2024.

Read more about:

Grain StorageAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like