In my last two columns I talked about the unusual nature of today’s corn and soybean markets. Prices are rarely this good for long, and nearby futures have hit the top of my projected selling ranges, based on current fundamentals of supply and demand.

All that begs the question, especially for new crop production ready to plant this spring: What should you be doing now to take advantage of these historic times?

There’s no one-size-fits-all answer. But there is a process to evaluate your choices and risk that can be adapted to most situations. Several examples follow, based on real-world conditions. But remember, every farm’s specific costs, yields, government program details, crop insurance and financial position are different.

Here’s what I’ve baked into these scenarios, based on conditions last week.

The assumed cost of production is $849 an acre for corn, and $601 for soybeans. These include around $40 per acre for operator labor but no return to management or additional family living expense. Other expenses are at market rates including fertilizer. Growers who booked or applied nutrients in the fall before prices took off likely will pay a lot less than those buying soon on the spot market.

Corn yields of 192 bushels per acre translate into a cost of $4.42 a bushel. Soybean yields at 56 bpa mean a cost of $10.73 per bushel.

The model assumes a double-barrel safety net: ARC-County for 2022 and Revenue Production crop insurance at 85% of trend-adjusted yield.

ARC protection varies widely depending on a county’s Olympic yields from 2016-2020, when the low and high years are eliminated at the rest averaged. ARC provides protection against falling revenues from lower prices and/or yields. Thanks to generous ARC yields in these examples – nearly 238 corn and 67 soybean bpa, the program guarantees $522 an acre for soybeans and $756 for corn, with payment on 85% of base acres.

Crop insurance is included as a cost of production, and isn’t cheap. But premiums of $29 per acre for corn and $20 for soybeans provide bang for the buck. Crop insurance spring prices are the average of new crop futures for February. So far, those are good: $14.25 soybeans guarantees $678 an acre with $5.85 corn giving $955 an acre projection. Those are futures-based revenues, but are above the projected projection costs for both crops after basis is deducted.

What to do?

So what do you do with all these numbers? One answer to that question, for those who can afford the risk, may be nothing. Thanks to the strong backstop from crop insurance and ARC, both corn and soybeans could be profitable under a wide range of both yields and prices.

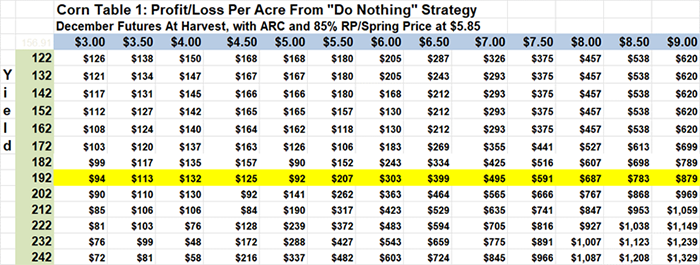

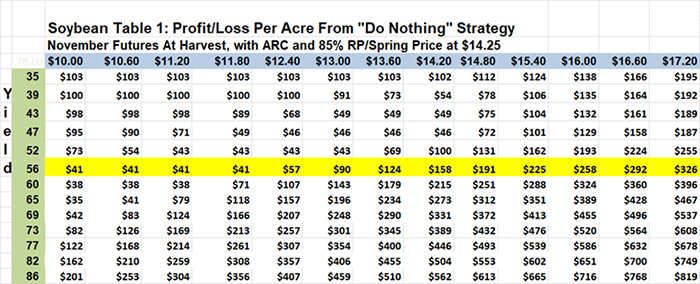

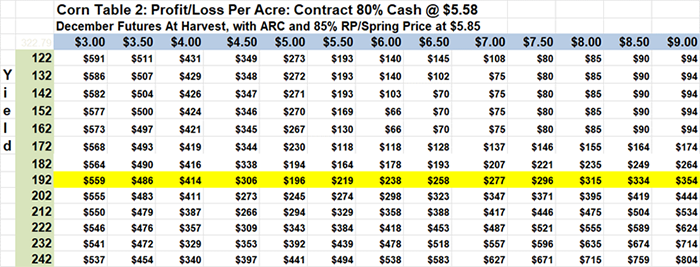

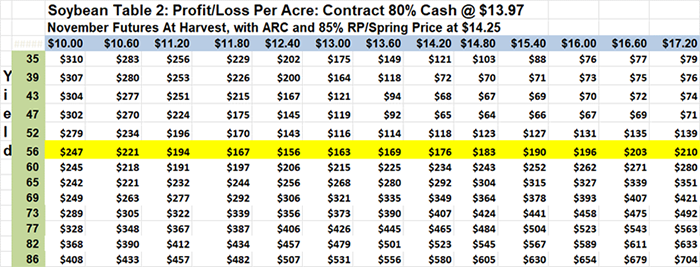

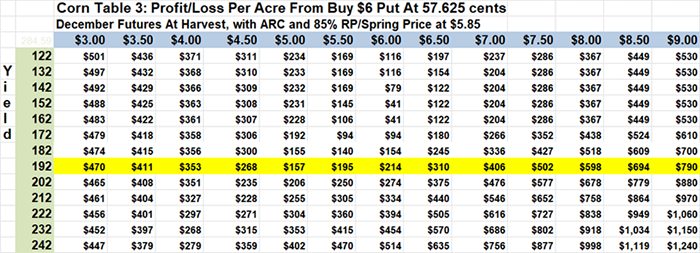

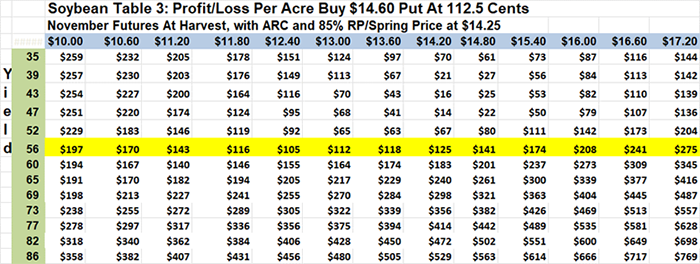

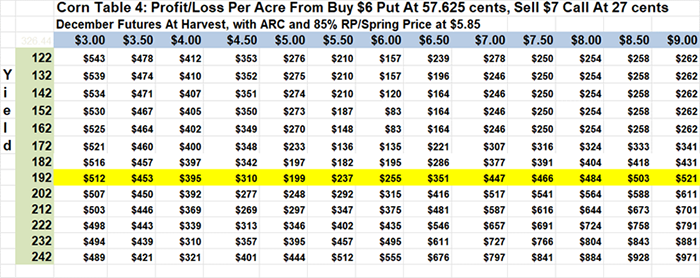

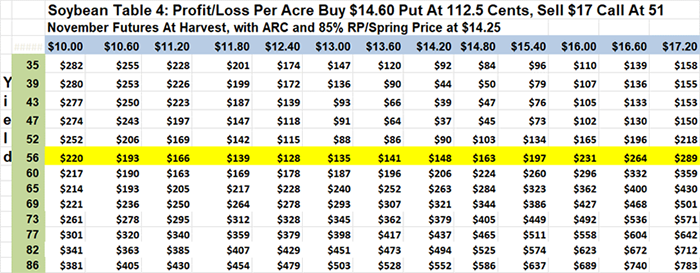

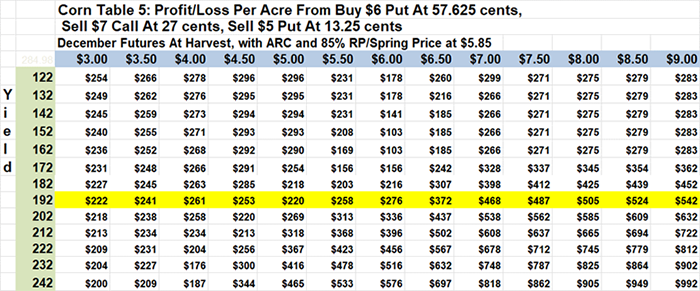

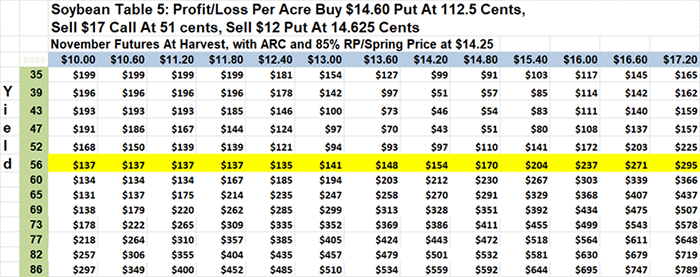

To come to that conclusion, I put together a sensitivity analysis using the Data Table function of the Excel spreadsheet. Each cell in the table shows the profit or loss per acre at different levels of yields and harvest prices. There are a lot of moving parts – the table automatically calculates what happens to revenues from marketing strategies, crop insurance and ARC under different scenarios. Assumptions about what happens to basis and government payments are two of the factors affecting revenues that could vary widely.

Table 1 shows what happens if no pre-harvest sales are made, with crops sold over the scale at harvest. All the numbers are in the black – a profit. Minimums and maximums are lower for soybeans than corn, in line with conventional thinking that says corn is indeed the more profitable choice this spring. Still, most growers will plant some beans, if only to keep rotations from getting out of whack.

Table 2 shows results if 80% of expected production, in this case the trend-adjusted yield, is forward contract on the current cash market. This increases profits if prices go down, though it also limits revenues if prices go up, especially if yields also go down.

Table 3 shows results from another marketing alternative. Instead of cash forward sales, a put option is purchased to cover downside risk. This allows greater upside if prices rise. But the puts are expensive: At-the-money soybean puts cost around $1.12 a bushel, with the corn equivalent nearby 58 cents. Some or all of that expense will be lost, even if prices fall and the options wind up in the money, lowering returns.

Table 4 shows what happens when the cost of the put is lowered by the sale of an out-of-the-money call option that earns revenue. This caps some of the upside from rallies but lowers the net cost of the transaction, increasing profit per acre if prices don’t surge enough to trigger exercise of the option.

Table 5 provides a second way of financing the put. In addition to selling a call, an out-of-the-money put is also sold, further defraying the cost of the long put. This caps some of the downside protection from the long put, but crop insurance and ARC may kick in to cover some of the revenue lost if prices fall.

Countless other alternatives exist – selling higher or lower percentages, or combining other futures, options and cash market positions. But these five cover the basic ones. Again, the key is not to base a decision on these examples, but to learn the process used to evaluate, or “stress test,” your plans. That may help you avoid a lot more stress, emotional and financial, in the long run.

Knorr writes from Chicago, Ill. Email him at [email protected]

The opinions of the author are not necessarily those of Farm Futures or Farm Progress.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like