Wes Perryman’s heirloom wheat is as steeped in history as the century-old farm he’s farming -- land first tilled by his great-great-grandfather in the late 1800s. Although he’s sowing varieties grown 100 years ago, Perryman hopes it will be the beginning of something new on his Moody, Texas, farm.

“This is my first year to grow heirloom wheat,” says the 36-year-old Perryman. “It’s a total experiment.”

Perryman is growing five varieties of wheat grown in Texas in 1919: Frisco, Purple Straw, Mediterranean, Knox and Fulcaster. Once harvested, he will deliver these heirloom wheat varieties to Austin, Texas, to Still Austin, a whiskey distillery which sources 100 percent of its ingredients from Texas farmers.

“We were curious what a whiskey might have tasted like in Texas 100 years ago, so we found a USDA agricultural census from 1919,” says Andrew Braunberg, Still Austin co-founder. “We began to look at the varieties, some of which had the reputation for being pretty good as old distiller’s wheat.”

Perryman, who also grows corn, cotton and wheat with his father on about 3,600 acres, sowed the heirloom varieties into a quarter of an acre on the farm where his grandfather was born and raised – a place Perryman now calls home.

“We’ve been looking for alternative markets, niche markets, to try to drive up our income,” says Perryman. “The commodity markets have been brutal, so we’re just trying to find a way to create a little more security and little less stress.”

In 2012, the markets skyrocketed due to drought in the Corn Belt, he says. “And we made some good money. But 2016 was tough on me. We got too much rain, made about half a crop and crop insurance didn't cover all my debt. So, 2016 was a big wakeup call.”

Though the high cost of farming inputs is a strain, Perryman’s quick to confess, “I love it and that's why I’m trying to find a way to create more security and less debt.”

SEED BANK

The heirloom seeds were originally acquired by Texas A&M AgriLife Research Assistant Research Scientist Russell Sutton, who got them from the National Small Grains Collection (NSGC) at Aberdeen, Idaho. The NSGC stores small grains germplasm collections, dating date back to 1897. The organization, part of the USDA-ARS National Plant Germplasm System, distributes seed to scientists worldwide for research, according to the NSGC website.

“Three years ago, they gave me 30 grams of each one of the heirloom varieties we selected,” says Sutton, who’s been working with Braunberg for several years to find small grains with a unique taste. “The first year, I planted 12, two-foot rows, harvested it and planted some larger plots. This year, I should produce close to 400 or 500 pounds of seed for him (Braunberg).”

SPECIALTY CHALLENGES

While a specialty crop may generate more income, Perryman confesses it has its own challenges. “The price for this wheat is higher and it takes a lot of attention,” he says. “Even sprinkling 17 pounds of seed with my 30-foot grain drill, because that's what I had, it just takes a lot of attention and thought. It’s different than filling up the drill and planting a whole field.”

See, Photo Gallery: Wes Perryman plants century-old wheat varieties

Inputs are about the same as his modern-day wheat varieties. “We put out the same shot of fertilizer when we planted it and we've top dressed it with nitrogen. It's had one shot of a fungicide so far.”

But Perryman is undecided how he will harvest his heirloom wheat. “I’ve been looking for a plot combine, and I have neighbors who have old Allis Chalmers pull- type combines, so I'm thinking that may be the way to go.

“This is ‘on the fly’ type stuff, but it’s really got my brain going.”

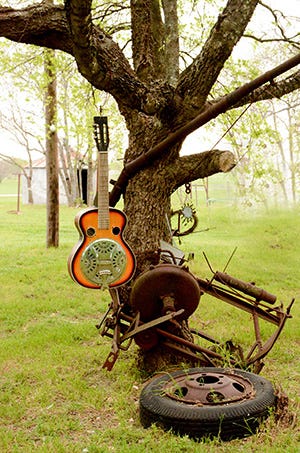

SINGING & PICKING

When Perryman isn’t farming, he’s singing and picking. This fifth-generation farmer and father of two, is also a Texas country songwriter, singer and electric guitar player for a band called Lilly and the Implements.

See, U.S. distillery market growing, heirloom wheat looks promising

“A lot of my early songs are about being newlyweds on the farm,” he says. “I wrote one song while I was on the tractor.”

He’s published songs such as, “Slow Dance with Me,” “This Old Town” and “10 Feet Tall.”

When asked if his passion is more for farming or singing, he says he wouldn’t be happy without either one. “It’s the whole concoction. I need both in my life.”

Perryman was first introduced to music by his family. “There’s a lot of musical talent in my family. My dad and aunts and uncles had a quartet in church. They sang acapella and even made a record when I was a kid.”

This Texas country musician began picking his guitar in high school. But his recent success, garnering gigs scheduled through June, has him a bit stressed. “I’m trying to make sure I stay on top of the farm and make sure everything gets done when it’s supposed to. It’s scary taking on a date because what if I’m in the middle of wheat harvest and I can’t leave?”

He says while it’s been interesting trying to wear two hats, musician and farmer, they’re very different. “I don’t want to be a star. I just like making good music and love the whole community of people.”

Growing heirloom wheat on his great-great grandfather’s century-old farm, harvested by old Allis Chalmers pull- type combine, just might be a Texas country song in the making.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like