The Bayou Meto Water Management District is addressing a water shortage problem in eastern Arkansas that, if not rectified, could endanger agricultural row crop production, a wildlife habitat, and impact consumer drinking water by the middle of the century.

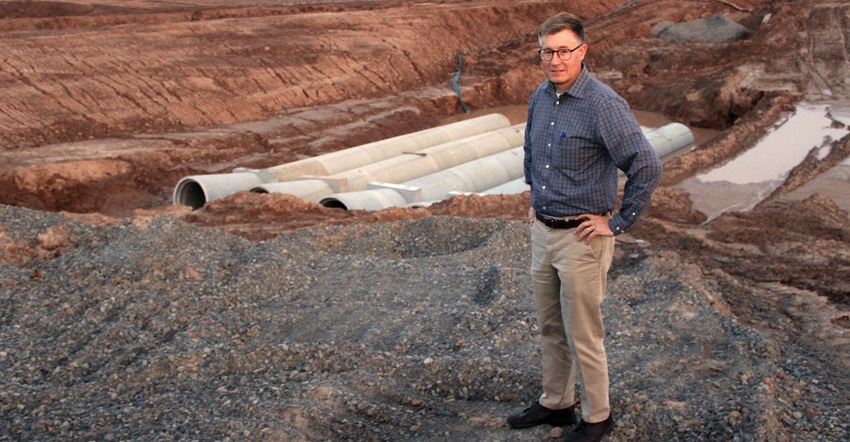

Agriculture is the number one industry in the state, and row crop production is the largest user of water. "Farming consumes nearly 80% of our state's water withdrawals each year," says Edward Swaim, executive director, Bayou Meto Water Management District, the organization behind the Bayou Meto Basin Project which encompasses the construction of a massive water distribution system of pipelines, canals, ditches, and pumping stations that will transfer much-needed surface water to 278,000 acres of irrigated crop land to supplement groundwater. "We are endangering our number one industry by pulling unsustainable amounts of water from right under our feet."

It is estimated that by 2050 only 20% of that 80% taken from below ground aquifers will be replaced by recharge. Swaim says a balance between ground water and surface water must be found.

Sustainable yield is a term being used to identify the quantity of water that can be withdrawn on a continuing basis without compromising the integrity of the Mississippi River Valley alluvial aquifer and/or the Sparta Aquifer.

The concept

Water will be taken from the Arkansas River by the Marion Berry Pump Station near Scott, Ark., and transferred via the project's canal system currently under construction. "The canals will carry water first to Indian Bayou and then continue on east through the area's natural drainage infrastructure," Swaim says. "Pipelines will run near farm property lines where farmers can access this surface water. This supplemental water source will help farmers preserve groundwater resources."

The Little Bayou Meto Pump Station was constructed in Reydell, Ark., close to the Bayou Meto Wildlife Management Area. That pump station will pull water out at the bottom of the water transfer system when needed. It will also provide flood control measures and reduce drainage problems within the wildlife area.

"The Marion Berry Pump Station can provide enough water, especially during a dry fall, to flood the wildlife area before duck hunting season," Swaim says. "The Little Bayou Pump Station will then drain water from the area after hunting season concludes, preventing damage to valuable bottomland hardwood forests."

Plans also include extensive channel cleanout and channel improvements within the wildlife area.

Depleting aquifers and funding

The Bayou Meto Basin Project is being constructed over the Mississippi River Valley alluvial aquifer where the lowest percentage of saturated thickness, or most depleted area, is located. "As that area of saturated thickness thins, cones of depression are created and that area of the aquifer loses water-holding capacity," Swaim says. "Pumping water is more difficult and the costs associated with pumping that groundwater increase significantly."

When the project started construction in 2010, it had a seven-year projected completion date. Nearly $37 million in federal stimulus money was matched by state funds which were used to build the pumping plants. Additional funding, contributed by the Corps of Engineers and matched by the Arkansas Natural Resources Commission and the Bayou Meto Water Management District, is being used for current construction efforts.

The goal is to have a self-sustaining water control/water supply system. "Our biggest issue of course has been financing," Swaim says. "We're also trying to determine how to use money from the Natural Resource Conservation Service to build part of the distribution system."

Swaim estimates they will be able to deliver irrigation water to farmers for a net cost of about $50 per acre-foot. "The most expensive part of the project has been the cost anything made of concrete," Swaim says. "The pumping stations were expensive, as was running dedicated power lines to them."

Obtaining additional federal money is a slow process. Swaim knows this groundwater problem is invisible to most Arkansans. "It's affecting their lives, but it's doing it at such a slow rate, it's difficult for them to see and/or understand its potential long-range impact on their lives," Swaim says. "Some farmers are building reservoirs or tailwater recovery systems, which is necessary because we not be able to deliver every drop of water they need when we have a dry week in the heat of summer."

Swaim explains this is the type of investment people made in the north Arkansas dams, like Greers Ferry Dam, that have been providing recreational water supply and flood control for decades. "Once we complete this project, people will think it wasn't a challenge, but it's been a huge undertaking and it will pay dividends to the farmers and others in this region for years into the future."

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like