Beyond any doubt, data drives agriculture in the 21st century. And as data continues to gain importance, questions arise on how to best manage and use all it to drive productivity and profitability on the farm.

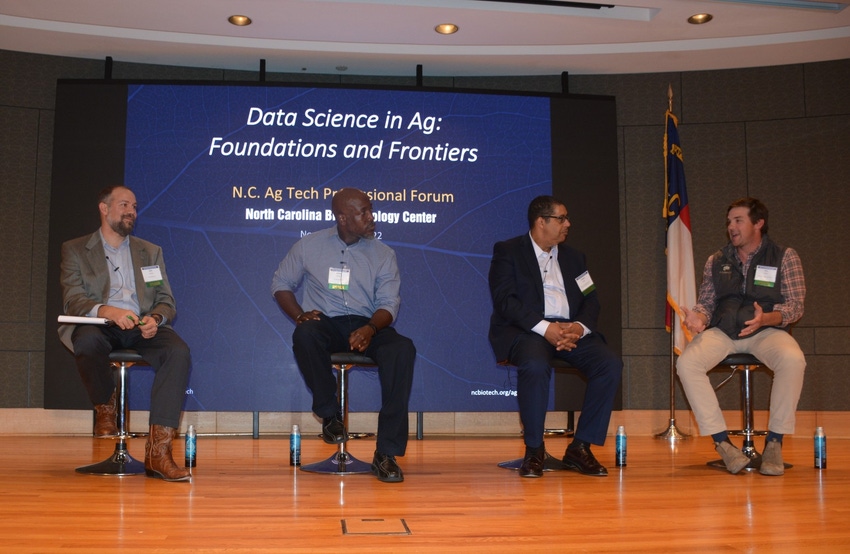

In a recent panel discussion on data science in agriculture at the North Carolina Biotechnology Center in Research Triangle Park, N.C., experts came together to highlight the challenges and future opportunities of “big data” in agriculture.

The discussion was moderated by Andy Curliss, national director, strategic initiatives with SAS Institute. Panelists were Wes Ward, senior vice-president, Harvey’s Fertilizer and Gas in Kinston, N.C.; Gregory Goins, interim associate dean for research and professor and chair, Department of Natural Resources & Environmental Design (Biomathematics) at North Carolina A&T University; Cranos Williams, professor, Electrical and Computer Engineering department; platform director for the Data-Driven Plant Sciences Platform, NC Plant Sciences Initiative; and John Gottula, director of crop science, agriculture, SAS Institute.

When it comes to data management and analytics on the farm, the biggest barrier to entry for many farmers is the cost, Ward emphasized.

“You’d be surprised that a lot of guys don’t have yield monitors in their combines. So how are they analyzing yield? They fill up a tender trailer, take it to a grain elevator, and divide the bushels by the acre,” Ward said. “If you want variable rate seeding for your farm, you have to have the planter to do that. That’s $150,000. A lot of these growers can’t afford that.”

Ward said another barrier is reliable technology. He noted that on Nov. 15, the day before the data science forum, Harvey Farms was planting wheat near Kinston, and planting had to stand still for six hours because the RTK (real-time kinematic positioning) tower that provides guidance for the planter was down, awaiting a software update.

“So, what did the guy do? He just kept planting. He didn’t worry about it. We didn’t have any data because he didn’t process it through the system,” Ward said.

Ward also believes more of the big ag companies such as Bayer, Syngenta and Valent will jump into the ag data market because of the profit potential, noting that selling products such as glyphosate has become less profitable and there are fewer novel chemistries on the market.

“We’re going to see more and more big companies get into tech because it is sexy to a certain degree, and it can be profitable,” Ward said.

Benefiting rural North Carolina

Goins said he hopes data science in agriculture could be adapted so it will help small farmers in regions of eastern North Carolina that were once dependent on tobacco and are now struggling. He said he hopes big data can be developed to benefit rural North Carolina.

“I hope it can somewhat lower the distance between the haves and have nots. You can only look at a few counties where all the wealth is, and the growth is stationed. I hope data science in ag can help bring back the fortunes of areas such as Fairmont, N.C., and Whiteville, N.C., that was based on the Golden Leaf. Data science can help where these famers just don’t go out on a limb thinking they are going to replace the Golden Leaf, but have a decision- making guide that can bring back these communities and have equity across our beloved state,” Goins said.

In the meantime, Williams said the emergence of data science in agriculture has transformed the way scientists in North Carolina deliver research to the farm. He stressed that the interdisciplinary research focus of the new Plant Sciences Initiative and the new Plant Sciences Building on the North Carolina State campus will improve research data delivery to the farm where it can be better used and lead to more effective solutions for agriculture.

Williams noted that electrical engineers and experts in other disciplines are now collaborating though the Plant Sciences Initiative to find data solutions for agriculture. He said when he joined the faculty of the College of Engineering in 2008, he was the only faculty member working in the ag sector. Now, five to six electrical engineering faculty members are working in agricultural research.

“If you look at the Plant Sciences Building, the building and infrastructure for the Plant Sciences Initiative, 25 % of the programs within that building are from the College of Engineering. There is an interest there. I think exposure is key. Having individuals providing pipelines, having individuals across these different disciplines, having the ability to understand and appreciate the types of problems growers face, I think is also key,” Williams said.

One issue each of the panelists brought up was the hesitancy of farmers to share their data. Williams noted that the North Carolina farmers he works with were particularly hesitant to share data with farmers outside of North Carolina and outside of the United States.

“They were more inclined to share that information with North Carolina growers as long as it didn’t get outside of the state or as long as it didn’t leave the U.S.,” he said. “They saw value in raising the economy of North Carolina as it related to their crop. They didn’t want their competitiveness to leave this state.”

Gottula noted that he works with a great deal of growers of greenhouse horticultural crops in his role at SAS, and he said these growers are willing to share data with the industry that serves them, but not with the public at large.

“Horticultural operations are intensely focused on product quality. Every little bit they can do to improve product quality, increase the number of bins that are Grade A, for example, that is a big result in their bottom line. They are willing to share their data and have someone help them,” he said.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like