April 13, 2021

An LSU graduate student has identified and named a new species of fungus that causes a devastating soybean disease.

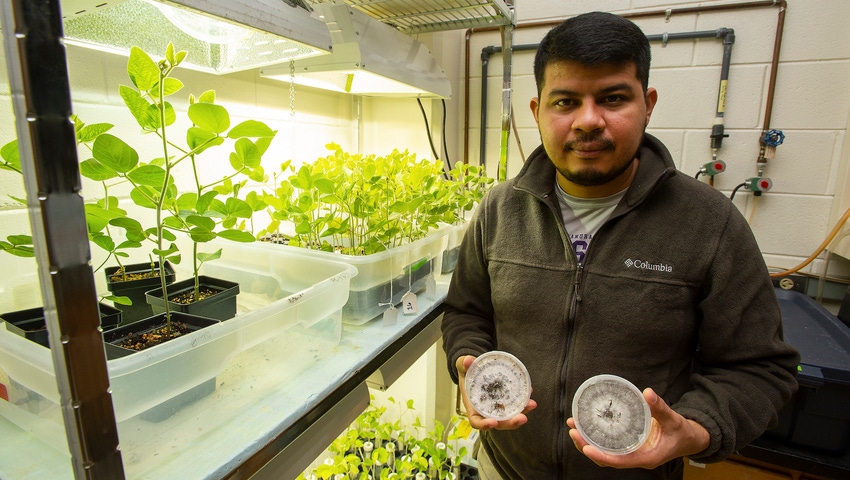

LSU doctoral student Teddy Garcia-Aroca identified and named the fungus Xylaria necrophora, the pathogen that causes soybean taproot decline. He chose the species name necrophora after the Latin form of the Greek word “nekros,” meaning “dead tissue,” and “-phorum,” a Greek suffix referring to a plant’s stalk.

“It’s certainly a great opportunity for a graduate student to work on describing a new species,” said Vinson Doyle, LSU AgCenter plant pathologist and co-advisor on the research project. “It opens up a ton of questions for us. This is just the tip of the iceberg.”

Taproot decline

The fungus infects soybean roots, causing them to become blackened while causing leaves to turn yellow or orange with chlorosis. The disease has the potential to kill the plant.

“It’s a big problem in the northeast part of the state,” said Trey Price, LSU AgCenter plant pathologist who is Garcia-Aroca’s major professor and co-advisor with Doyle.

“I’ve seen fields that suffered a 25% yield loss, and that’s a conservative estimate,” Price said.

Louisiana soybean losses from the disease total more than one million bushels per year.

Price said the disease has been a problem for many years as pathologists struggled to identify it. Some incorrectly attributed it to related soybean diseases such as black-root rot.

“People called it the mystery disease because we didn’t know what caused it.”

Price said while Garcia-Aroca was working on the cause of taproot decline, so were labs at the University of Arkansas and Mississippi State University.

Price said the project is significant. “It’s exciting to work on something that is new. Not many have the opportunity to work on something unique.”

Research

Garcia-Aroca compared samples of the fungus that he collected from infected soybeans in Louisiana, Arkansas, Tennessee, Mississippi and Alabama with samples from the LSU Herbarium and 28 samples from the U.S. National Fungus Collections that were collected as far back as the 1920s.

Some of these historical samples were collected in Louisiana sugarcane fields, but were not documented as pathogenic to sugarcane. In addition, non-pathogenic samples from Martinique and Hawaii were also used in the comparison, along with the genetic sequence of a sample from China.

Garcia-Aroca said these historical specimens were selected because scientists who made the earlier collections had classified many of the samples as the fungus Xylaria arbuscula that causes diseases on macadamia and apple trees, along with sugarcane in Indonesia. But could genetic testing of samples almost 100 years old be conducted? “It turns out it was quite possible,” he said.

DNA sequencing showed a match for Xylaria necrophora for five of these historical, non-pathogenic samples — two from Louisiana, two from Florida, and one from the island of Martinique in the Caribbean — as well as DNA sequences from the non-pathogenic specimen from China. All of these were consistently placed within the same group as the specimens causing taproot decline on soybeans.

Why now?

Garcia-Aroca said a hypothesis that could explain the appearance of the pathogen in the region is that the fungus could have been in the soil before soybeans were grown, feeding on decaying wild plant material, and it eventually made the jump to live soybeans.

Arcoa’s study poses the question of why the fungus, after living off dead woody plant tissue, started infecting live soybeans in recent years. “Events underlying the emergence of X. necrophora as a soybean pathogen remain a mystery,” the study concludes.

But he suggests that changes in the environment, new soybean genetics and changes in the fungal population may have resulted in the shift.

The lifespan of the fungus is not known, Garcia-Aroca said, but it thrives in warmer weather of at least 80 degrees. Freezing weather may kill off some of the population, he said, but the fungus survives during the winter by living on buried soybean plant debris left over from harvest. It is likely that soybean seeds become infected with the fungus after coming in contact with infected soybean debris from previous crops. These hypotheses remain to be tested.

Many of the fungal samples were collected long before soybeans were a major U.S. crop, Doyle said. “The people who collected them probably thought they weren’t of much importance.”

Garcia-Aroca said this illustrates the importance of conducting scientific exploration and research as well as collecting samples from the wild. “You never know what effect these wild species have on the environment later on.”

What’s next?

Now that the pathogen has been identified, Price said, management strategies need to be refined. Crop rotation and tillage can be used to reduce incidence as well as tolerant varieties.

“We’ve installed an annual field screening location at the Macon Ridge Research Station where we provide taproot decline rating information for soybean varieties,” Price said. “In-furrow and fungicide seed treatments may be a management option, and we have some promising data on some materials. However, some of the fungicides aren’t labeled, and we need more field data before we can recommend any.”

He said LSU, Mississippi State and University of Arkansas researchers are collaborating on this front.

Doyle said Garcia-Aroca proved his work ethic on this project. “It’s tedious work and just takes time. Teddy has turned out to be very meticulous and detailed.”

The final chapter in Garcia-Aroca’s study, Doyle said, will be further research into the origins of this fungus and how it got to Louisiana.

Source: Louisiana State University, which is solely responsible for the information provided and is wholly owned by the source. Informa Business Media and all its subsidiaries are not responsible for any of the content contained in this information asset.

You May Also Like