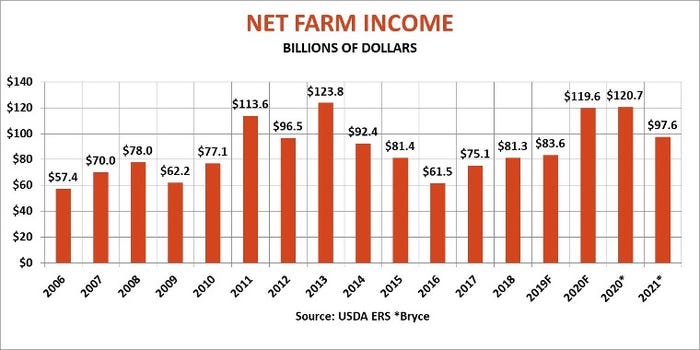

You likely saw the headlines earlier this month and maybe winced a little. While the economy continues to wrestle with the fallout from COVID-19, USDA forecast net farm income would jump 43% for 2020, to $119.6 billion.

Many of these stories noted the main reason for agriculture’s showing: Direct government payments. They could surge to a record $46.5 billion, even as crop prices finally started to improve.

Farmers I’ve talked to over the past 30-plus years have a love/hate relationship with farm programs. They don’t like it in principle. Most sign up, because it makes economic sense. That’s especially true when the rules of the market go haywire.

When markets don’t work

Anyone involved with buying and selling corn and soybeans knows the role of supply and demand. But sometimes markets don’t work, and I say that as somebody who lives blocks from Milton Friedman’s onetime home on the South Side of Chicago.

The past couple years are a case in point. The trade war with China left U.S. soybean farmers facing a cliff. Coronavirus only spread the pain.

Still, even in the depths of the 1980s Farm Crisis when I started at Farm Futures, some growers resisted the lure of Washington’s bucks. While everyone else in the neighborhood signed up, they kept going without deficiency payments, the CRP or PIK certificates. Or later, ACRE, PLC, ARC, etc.

Their feelings are familiar. A century ago after World War I, my grandfather kept his observations in notebooks sponsored by the coal company -- hybrid seed corn wouldn’t become popular for another decade or so. At one meeting he heard talk about the need to guarantee farmers a profit. He was already skeptical of what would become the parity plan in the 1930s. Grandpa Stocker’s judgement: Paying farmers to produce would lead to overproduction and lower prices. Time has proven that assessment correct.

I don’t know if it’s genetic memory, but that idea seems to be ingrained with some of us. That’s why so many farmers, when interviewed, said the recent round of payments was nice, but they’d rather make a living from the market.

Hopefully, farmers and everybody else will have a chance to abide by Adam Smith’s “Invisible Hand,” sooner rather than later. I suspect a lot of corn and soybean farmers will do just fine. But the bottom line for net farm income likely will show a substantial drop in 2021.

Less government aid ahead

My current forecast for 2021 puts NFI at $97.6 billion. That would be down 18% from this year, but still represent the second most since the all-time record of $123.8 billion in 2013.

Stronger crop prices should help, and the livestock industry could also recover a little from the devastation caused by the coronavirus. Expenses will be higher as fuel and fertilizer markets bounce back. But the biggest factor in my estimate is less aid from the government.

Normal yields and higher prices mean most producers won’t get a whole lot from traditional farm programs like ARC and PLC. Still, some type of emergency relief is likely if the logjam in Washington finally clears. While final numbers are still up in the air, the compromise packaged under debate this week could include $13 billion for agriculture. If so, total direct government payments could drop to $24.2 billion, down $22.3 billion from 2020.

To be sure, my estimates have all sorts of “ifs, ands, or buts.” Growers who have converted cash to accrual records know that net farm income includes a series of adjustments to cash transactions that can be very hard to predict when scaled nationally.

Inventory changes – the difference between values at the beginning and end of the year -- are always tricky to figure. Will farmers store more of their 2020 crop until January 2021 due to higher income from Uncle Sam? Or will they take the money from the today’s better markets and run – and offset the revenue with higher prepaid expenditures? Many farmers are figuring busy right now trying to answer these questions with the help of their accountants.

Higher depreciation

Machinery purchases as farmers replace older equipment lines could increase depreciation, another murky line item expense in USDA’s forecasts. “Capital consumption” is the accounting term the government uses. To understand that, consider whether or not your farm “lived off depreciation” the last couple of years.

But the bottom line seems clear. If the world returns to “normal” in 2021, get ready for less.

Knorr writes from Chicago, Ill. Email him at [email protected]

The opinions of the author are not necessarily those of Farm Futures or Farm Progress.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like