There’s no single secret to success in agriculture. Even so, more than a few farmers have tested the “bigger is better” magic bullet by increasing acres as they search for better efficiencies and more bushels to fuel profitable production.

Sometimes, bigger is better. But the odds aren’t necessarily in your favor.

North Dakota farmer David Glinz says he learned that lesson the hard way. After four years of losing money from low commodity prices, his cash flow was more than a little out of whack, and his operational loan kept growing. After a heartfelt meeting with a farmer peer group, Glinz auctioned off $7 million worth of land (including 1,800 acres) and equipment in early 2018 to pay down his debt and correct the course of his operation.

“Cutting back may not be the best bet for everyone, but it was the right thing for me to do,” he says. “I could have refinanced and battled it out, but I’m not sure we would have survived long term that way.”

The move was successful, with Glinz making a return to profitable production last year. He says joining the peer group was one of the best things he’s ever done in his farming career.

“I’m in a fantastic group, and I really trust their honesty and integrity,” he says.

Risky business

Adding acres can add significant revenue to a farming operation — but it also can add significantly more risk, notes Bryce Knorr, Farm Futures senior grain market analyst.

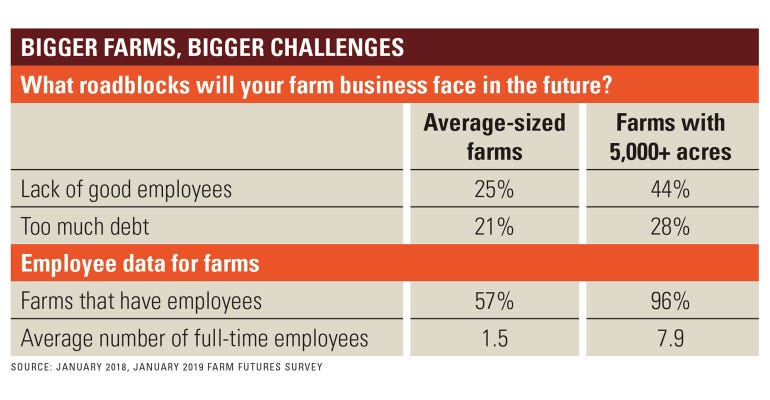

Stack up enough risk, and a farm becomes vulnerable as it faces negative income and a debt-to-asset ratio above 40%. Across the industry, about 3% to 4% of farming operations fit this definition. As farms increase to around 7,500 acres, the percentage of vulnerable farms balloons to about 11%.

“Larger farms have always been about three times more vulnerable — even in 2012, when much of the farm economy was booming,” Knorr says.

Several years later, it’s not getting any easier for large farms, he adds.

“Getting large can be a path to reward, but that also means more debt,” he says. “The last few years have made it hard to service that debt. That has put more of these large farms under intense financial pressure.”

Larger farms face not only more financial pressure, but also the pinch of time management. They may inherit new HR headaches. They may even find their role on the farm shifting in new, uncomfortable ways.

So what are farmers to do when they grow acres faster than their financial and management expertise?

Got strategy?

Idaho-based financial consultant and rancher Dick Wittman says growing your operation’s size can be a noble goal — just make sure there’s strategy behind that goal. Don’t just grow bigger, grow smarter.

“There’s way too much emphasis on growing yourself out of a problem and not enough emphasis on being strategic about your problems in the first place,” he says. “No matter your vision, you need to strategically manage for your size of business.”

There is more than one type of family farm, Wittman says. He suggests first determining where you fall on that spectrum. So-called lifestyle farmers inhabit one end of the spectrum. These farmers are able to enjoy all of the benefits and accessories of living in the country, but the operations aren’t necessarily designed to be fully sustainable, especially beyond retirement.

“Outside income is typically required in these operations,” he says. “The plan is more often renting the land in retirement rather than passing it along to the next generation.”

On the other end are fully integrated, sustainable, competitive, innovative operations with an eye toward the future, Wittman says. They pay all employees a living wage, and keep current with ag tech and equipment to optimize efficiencies.

However, most farms don’t occupy either of these categories, landing instead somewhere in the middle, Wittman says. “A lot of farms don’t even want to get bigger,” he adds. “And that’s fine — they just need to look at how they can gain a more competitive cost structure.”

That may mean sharing equipment or even a CFO with neighbors. But before they make those considerations, farmers who are concerned about right-sizing their operations should look at three things first, Wittman says:

1. financial structure that includes working capital and profitability

2. true cost of production, measured against peers

3. business governance structure

That third point covers any number of critical HR practices, including job descriptions, training and team communication, Wittman says. Farmers who have a formal structure in place can deploy a robust strategic planning process that allows them to function efficiently throughout the year, even as their operation grows.

“With it, you’re able to look at today, this week, this month and this season,” Wittman says. “When everyone has clearly assigned roles and there’s a clear delegation process, it solves a lot of time management problems.”

If your business governance structure is highly informal, “it’s mostly in your head,” Wittman says, adding it may be wise to start writing down those processes. “Not doing that can create a lot of anxiety and a lot of wasted time.”

“No matter your vision, you need to strategically manage for your size of business,” says rancher and farm consultant Dick Wittman.

Change your role

Farmers tend to outgrow old practices in four key areas, according to Tim Schaefer, founder of Minnesota-based Encore Consultants. Usually, the first thing to change is his or her daily detail management style.

“In early stages, the farmer expects to know everything about everything,” he says. “He or she does at least as much physical work as their employees, and often more. Employees make few, if any daily decisions.”

Eventually, this level of detail management by the owner is not sustainable, Schaefer says.

Echoing Wittman’s sentiments, Schaefer says informal decision-making processes can work well for smaller operations, but this management style is quickly outgrown as the operation takes on more acres, more employees and more business partners.

“Miscommunication, increased conflict and fuzzy goals are the result,” he says. “There are challenges with a larger workforce that aren’t applicable to smaller farms. Communication, compensation and employee retention are just a couple of examples.”

Time is another resource that becomes increasingly precious as an operation grows. Everyone is given the same 24 hours in a given day, Schaefer says. “There is a point in no man’s land where time demands on a farmer drive any semblance of a balanced life to the back burner. It’s 24/7 for 365 days a year, and the pace gets more frantic each year. There simply isn’t more time.”

Farmers facing this situation have one of two basic options, Schaefer says: Adjust up, or adjust down.

Sometimes scaling back is the most prudent choice, he says. For those committed to growth, some fundamental changes in the way they manage people, processes, time and money might be in order.

For some, that might require hiring outside help to move to accrual and managerial accounting. For others, creating systems around communication, decision-making and workflow will help ease the burden of time.

“If you are now stuck but choose to scale up, the steps are easy to understand but sometimes hard to execute,” Schaefer says. “And the exact answer will be a little different for each individual operation.”

It’s human nature to underthink risk. People sometimes put on blinders and charge ahead, thinking they can still do it. Risk can be a valuable driving force when it pushes innovation — just don’t allow that to turn into hubris.

“It’s a cautionary tale,” Knorr says. “Make sure you can chew whatever you bite off.”

At 73 years old, Glinz has had time to season his farm business skills for nearly five decades. Remaining humble, he admits skill isn’t the only factor at play in this industry.

“Some of it is just pure luck,” he says.

Scale up smartly

Scaling up used to be the “secret sauce” for a lot of farmers, but these days it takes some strategy to get bigger successfully, according to Alan Grafton, AgKnowledge director with K-Coe Isom.

“Whenever you add ground, do you also need to add labor and equipment, or can your operation absorb those acres with what you already have on hand?” he asks.

For example, adding 200 acres might really help your bottom line. But if you’re also adding another employee and another tractor to farm that ground, it may be adding more financial stress to your operation instead of more revenue.

Other operational decisions, such as rotating crops, or converting acres to organic or non-GMO production, will also affect the labor-equipment matrix.

Some farmers would rather spend most or all of their time in a field rather than in an office. Calibrating equipment, setting spray rates and making field passes are all critical components of growing profitable crops. But these are all tasks that trusted employees could be trained to do over time, Grafton says.

“You’ll reach a point where doing everything yourself is not really possible,” he says. “You’re just one person, and you need to learn to rely on others to trust your land and farm it like it’s theirs.”

Success — whether on a single field or across the entire operation — ultimately tends to boil down to three primary factors: yields, price of sales and cost of operation.

“You have to grow well — don’t just grow for the sake of growth,” Grafton says. “Ask if your land is adding to the bottom line. Measuring the bottom line is the result the grower needs to focus on.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like