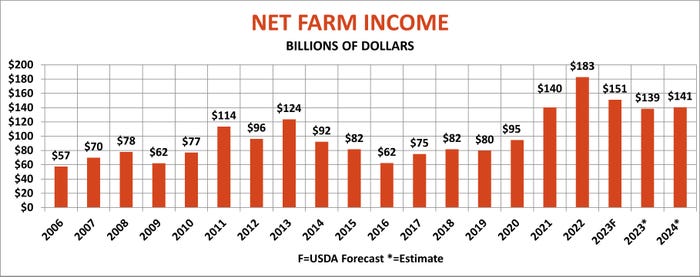

Even if you haven’t sat down with an accountant for a year-end tax review, it hardly takes a CPA to recognize the bottom line from USDA’s latest forecast for 2023 net farm income. Spoiler alert: Profits are headed south, especially for row crop operators.

The government predictions out Nov. 30 didn’t address potential for 2024, but other data released over the past month suggests hope that returns could at least stabilize.

And the agency’s Economic Research Service forecast for 2023 income of $151 billion may be optimistic, even though it sees profits down 17% from the record set in 2022.

Crystal-balling farm revenues and costs months before crops are harvested in the U.S. and around the world is a guessing game to be sure, especially when the books have yet to close on this year’s performance. Indeed, USDA based its update on numbers from early October, when most crop and livestock markets were higher, before downgrades for corn, wheat, cotton and hogs in the latest World Agricultural Supply And Demand estimates Nov. 9.

Nonetheless, here’s what the “official” forecasts show, along with my own models for corn and soybeans.

Farmer behavior

First off, 2023 returns won’t really be known for months. One obvious question mark is just how much this fall’s harvest is worth. USDA won’t finalize its estimates for 2023 corn and soybean yields and acreage until the Jan. 12 WASDE. Average cash prices are also in flux. Official monthly averages are out for only September and October – estimates for the rest of the marketing year are based in part on basis expectations and 2023 crop delivery futures trading, which could change dramatically.

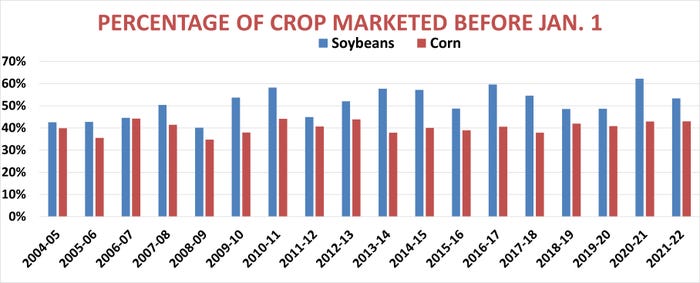

Farmer behavior also figures in, because monthly averages are weighted by the percentage of the crop marketed in a given month. The pace of sales varies depending on prices and production – more tends to be sold or forward contracted when prices are higher. Income taxes and cash flow also figure in, as farmers juggle sales from one calendar year to the next depending on year-end tax reviews now underway as growers try to figure out the how much to accelerate expenditures to take advantage of pre-pay discounts and minimize taxable income.

The portion of the crop sold before Jan. 1 tends to be more stable for corn, but still varied by up to almost 10% over the past 20 years. The pattern of soybean sales is more unpredictable, with a range of more than 20%. These patterns can affect accrual inventory adjustments made to align crop years for farmers with calendar years used by most taxpayers.

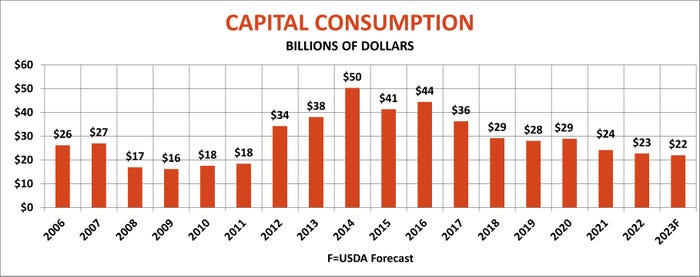

Some of USDA’s calculations can change even more dramatically from year to year, making them especially hard to predict. “Capital Consumption” – a placeholder for depreciation of buildings and equipment – ranged from $50 billion in 2014 to just $22 billion in 2023, affected by both economics and tax policy.

No laughing matter

All of these factors make forecasting net farm income difficult at best. At one meeting of economists a speaker’s eyeroll at these convoluted calculations got big laughs, something that’s not easy to get from that audience before cocktail hour.

For example, I adjusted USDA’s 2023 estimate with data from the latest WASDE, which suggests crop revenues could be nearly $20 billion lower, with livestock sales down almost $10 billion. Costs could be less too, but not by as much. As a result, my bottom line is for income around $137 billion, down another 8% from USDA’s forecast.

The good news, if there is any from these machinations, is potential for net farm income to rebound – maybe – in 2024.

First, I looked at what USDA said about the coming year in its updated “baseline” put out Nov. 7 as a part of the federal government’s budgeting process. These outlooks didn’t include a net farm income forecast, but did make estimates for major crops and livestock revenues and variable expenses.

Based on these, cash crop receipts could continue to fall in the year ahead, but the livestock sector could enjoy better sales, while costs could be the lowest since 2021. Net farm income would be around $147.5 billion, 6% higher than my estimate for 2023 but still down 2% from USDA’s figure at the end of November.

Trouble is, USDA’s 2024 baseline may be too optimistic for corn and soybean revenue, using higher corn yields and higher corn and soybean prices that my model sees ahead.

Obviously, a lot could change, making these broad-based outlooks of use to policy makers and headline writers, but of limited value to growers. What matters are the estimates for your own operation. So sit down with your accountant, if you have not yet done so for 2023, and then pencil out 2024 numbers to set where you’re headed.

Knorr writes from Chicago, Ill. Email him at [email protected].

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like