As the Illinois frost-free season has grown an average of nine days over the past 70 years, farmers have observed a generational change: Planting has gone from mid-May to mid-April — except in 2019.

During that 70 years, there’s been an average 2.1-inch increase in total rainfall for the state between April and October. That rain is coming down in larger events. While the western Midwest faces more potential for dry spells, Eric Snodgrass says Illinois droughts are getting shorter and aren’t lasting for multiple seasons.

“Our problem in Illinois is not heat; it’s too much water,” says Snodgrass, principal atmospheric scientist at Nutrien Ag Solutions. “It does not mean there will not be drought in the future, but the longer-term trend is we’re getting a little bit wetter.”

When asked about North Dakota’s average 35-day growth in the frost-free season over the past 70 years, Snodgrass says states that are benefiting from the corn and soybean belt growing larger are more sensitive to huge swings in weather because of lower-quality soil.

“The longer-term trend is warmer for that part of the country, and they’re getting plenty of water as well. The difference is, we can hold on to it when we get dry conditions like we had in July and August,” Snodgrass says, referring to a 62-day period in 2019 that featured only a handful of days where most Illinois farmers got more than a half-inch of rain. Without Illinois’ water-storing soil, “this would have been disastrous for yields.”

Snodgrass says the wetter trend for the Midwest is taxing infrastructure built to withstand 500-year floods. Extreme flooding events like what happened in Illinois in 2019 are likely to happen more often, according to climate models used in the National Climate Assessment that charts the impact of rising greenhouse gas emissions.

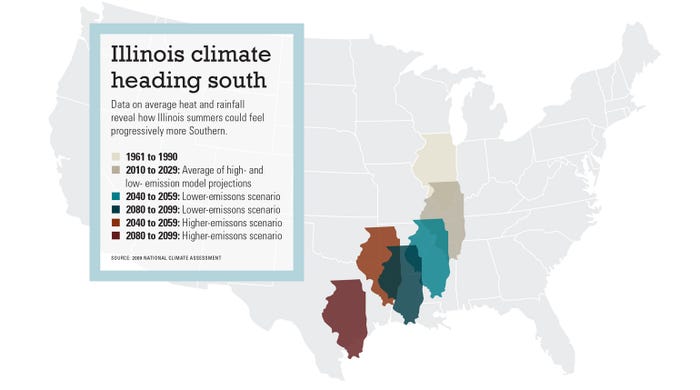

The 2009 assessment released projections for a change in Illinois climate based on two emissions scenarios. As the models anticipated, warmth caused by emissions have made Illinois wetter with higher minimum temperatures (see graphic below).

Trent Ford, Illinois state climatologist, says Illinois experienced its wettest January to June on record in 2019. He says it’s unlikely the record will be broken in 2020.

2019 was unique in that total rainfall fell short of a year like 2009 at some weather stations, but the dry periods between rains were shorter, with an average of 2.5 dry days between rains as opposed to 3.5 days in 2009, recorded at the Peoria weather station and elsewhere in the state.

“We’re seeing wetter springs, wetter winters, and the trends are consistent with increased global average temperatures. Warmer air can generally hold more water,” Ford says, pointing to how the Peoria weather station shows a 10% chance of 2019 repeating next year based on observations over the past 30 years. If he expands his look over the past 100 years, it would be closer to 4% because the first 70 years were drier with cooler global temperatures. Thirty years is the minimum for climate trend analysis due to variability in weather.

“Whenever we have a really strange season, we tend to have a regression back toward the mean,” he adds. “We’ve seen in the last 3 of 10 years, we’ve had those really wet springs and winters where we have precipitation falling on many days. We probably won’t break records again next year, but this is the trend we’re seeing.”

Rising temperatures

Illinois’ maximum temperatures have decreased by an average of 0.75 degree F over June, July and August during the past 70 years, while the minimum has increased 1.5 degrees F. Snodgrass says the state is getting warmer at night without much of an increase in afternoon temperatures, while other areas of the globe have increased temperatures across the entire length of the day.

“The ocean temperature change in the Pacific has been getting hotter, and that is favoring more ridging in the jet stream out west, which means that’s where the heat is. We’re on the downstream side of that, and as a consequence, we’re going to be on the cooler side of the flow pattern. That’s hugely beneficial to Illinois ag,” Snodgrass says.

Climates of growing regions around the world such as the Eurasian wheat belt are trending drier, but the Midwest, and Illinois in particular, are bucking the trend, thanks to the way the Rocky Mountains channel weather circulations spawned in the Pacific Ocean.

“We are basically letting that mountain chain channel more cool air into this area, and where it meets with a front, we get rain,” Snodgrass says, adding the drought pressures present in the western part of the Corn Belt, in Europe and elsewhere are hitting Illinois less severely because of the way the Rockies move weather fronts. When the pressure does hit, its impact is lessened by healthy soil.

“This is the only place I get to go in the world and have a positive message about a changing climate,” he adds.

A modern-day La Niña, which occurs when Pacific Ocean temperatures are cooler than average, is actually warmer than it was 25 years ago with a strong, warm El Niño. La Niñas portend a hot and dry growing season for Midwest farmers, and as time has progressed, the ocean — a storehouse for 90% of global warmth — has released more and more heat into the atmosphere.

Year after year, the jet stream shoots the heat into Canada and Greenland, which then pushes the cold air of the arctic into Illinois and increases the frequency of flooding events.

Dealing with rain

“I’m not looking forward to more flooding,” deadpans Garrett Hawkins, who farms near Valmeyer, Ill., in the Mississippi River bottoms.

Hawkins claimed 25% of his acreage under prevented planting in 2019, a record for his family’s farm. While none of the levies broke around him, he had to close the drain leading out of his fields once the Mississippi tributary adjacent to his farm rose above 27 feet. Rains kept coming and he couldn’t drain those fields for five months. Normally, he shuts off the water outlet for no more than three weeks a year.

“The record for the river was 49 feet in 1993. This year was the second highest, 46.2 feet,” Hawkins says, adding the levee broke in ’93 and flooded his childhood home.

“In ‘93, we had what I would call a normal spring locally. But what killed us was so much water up north in Iowa and Nebraska. This year, similar deal — all the rain up north ended up down here, but locally we also had heavy rain. So, folks couldn’t get their fields dry, and there was a lot of area that was prevent plant.”

Like many river bottom farmers, Hawkins spends the off-season moving earth, digging out ditches and shoring up terraces with his hydraulic excavator. He says his efforts help move water to outlets faster, but in 2019, the water couldn’t leave until the growing season was almost over. By June, water seeped up on his side of the levee, and on one of his farms, he had to put sandbags around geyser-like holes that were pushing sand above the topsoil.

“We call them sand boils. You take sandbags and make a ring around that to fill it full of water and equal out the pressure,” Hawkins explains. It might take a couple of rows of sandbags, or it might need to be built five sandbags high.

DIGGING: Garrett Hawkins digs ditches during every off-season, like many other river bottom farmers. His earth-moving efforts couldn’t push water off his fields for five months while the river his farm drains into remained high.

While most Illinois farmers don’t farm adjacent to the Mississippi River and won’t need to manage sand boils, they can still pick up strategies Hawkins and neighboring farmers deploy to help alleviate the pressure from wetter growing seasons: They can plant cover crops, install tile and buy earlier-maturing seed for acres that are more likely to be water-logged in a given planting season.

“You have more frost-free days in a typical year, and you can go after a higher-maturity corn,” Snodgrass says. “Plant 115-day corn in April because you’re going to get it. But you have to manage your water well so that you can plant on time.” He adds that April-planted, late-maturing corn did well in 2019 so long as it wasn’t drowned out by the torrent of rain in late April and May. Tile drainage helped.

Hawkins planted cover crops on his prevented planting acreage in August. He says it was the only option available to him since soybeans wouldn’t have matured before the first frost. His goal was to improve soil health and to get some bales of millet out of a bad year. Plus, cover crops can help increase the rate of water infiltration and retention.

“If we can handle these big rainfall events and use them to our advantage, there’s no limit to what we could do in terms of productivity growth,” Snodgrass says. “We are positioned even with changes in climate to do well, but it’s all about managing water. It’s our biggest stress in the near term, and it’s certainly been our stress for the last few years.”

Snodgrass and Hawkins have both noticed a surge in tile drainage installation as well, which helps in areas that aren’t limited by a full outlet like the Mississippi River tributary Hawkins drains into. To help limit the risk of water spilling over the levy in the future, Hawkins says he wants to see further infrastructure development.

He also says areas in Missouri that hold water for wildlife conservation purposes discharged into the Mississippi at an inconvenient time this spring, adding water to an already filling river.

“The main reason it was designed was for water navigation and flood control. Whenever that river shuts down and they can’t have traffic, it just cripples us. It hurts everybody. Doesn’t matter what kind of consumer you are, it hurts everyone,” Hawkins concludes. “Having control of the river by fixing our outdated locks and dams and having a more common-sense approach to water control definitely would benefit the entire population.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like