If you work the land in parts of Illinois, you know it’s dry.

Really dry.

Drier than it really ought to be in January.

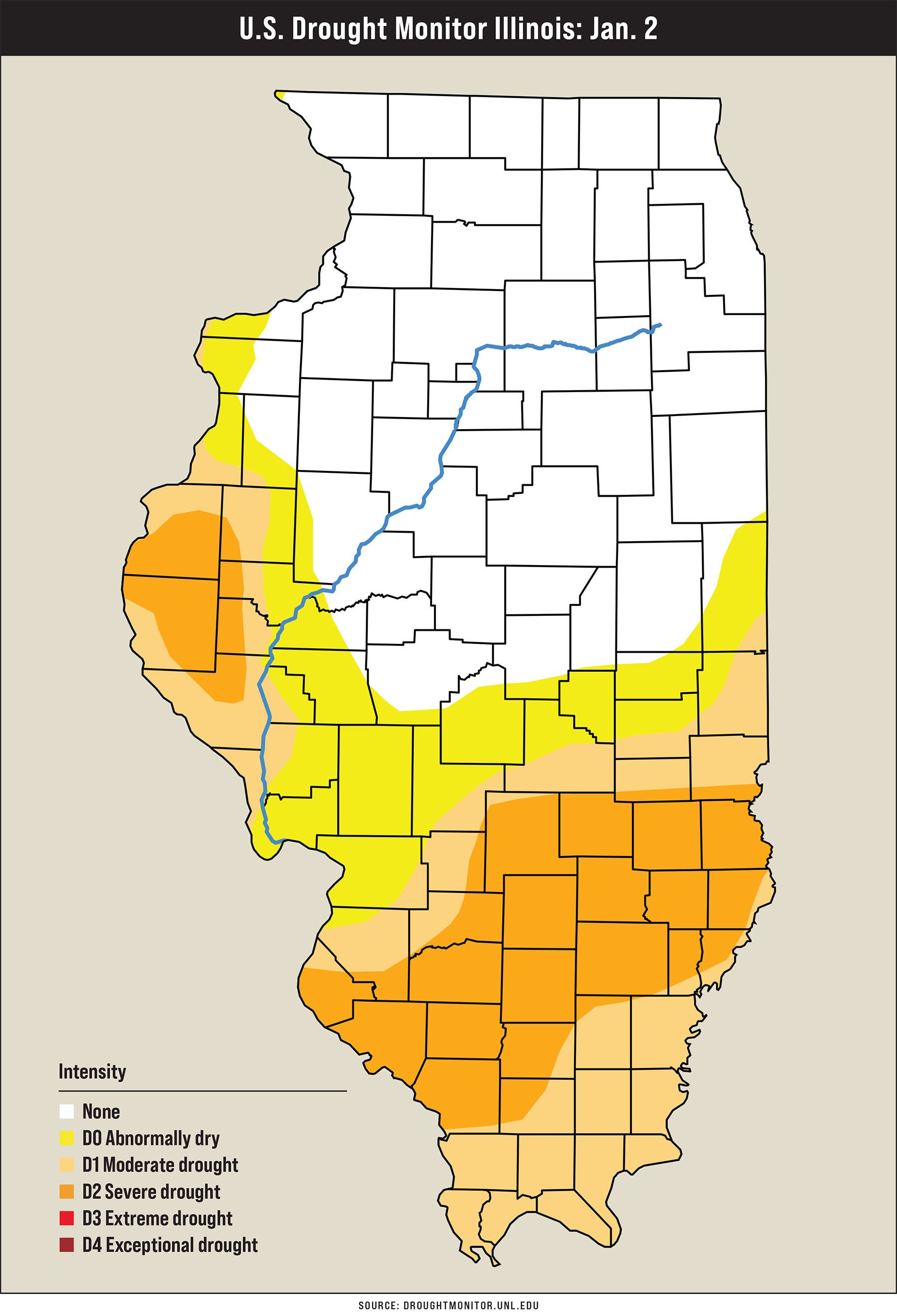

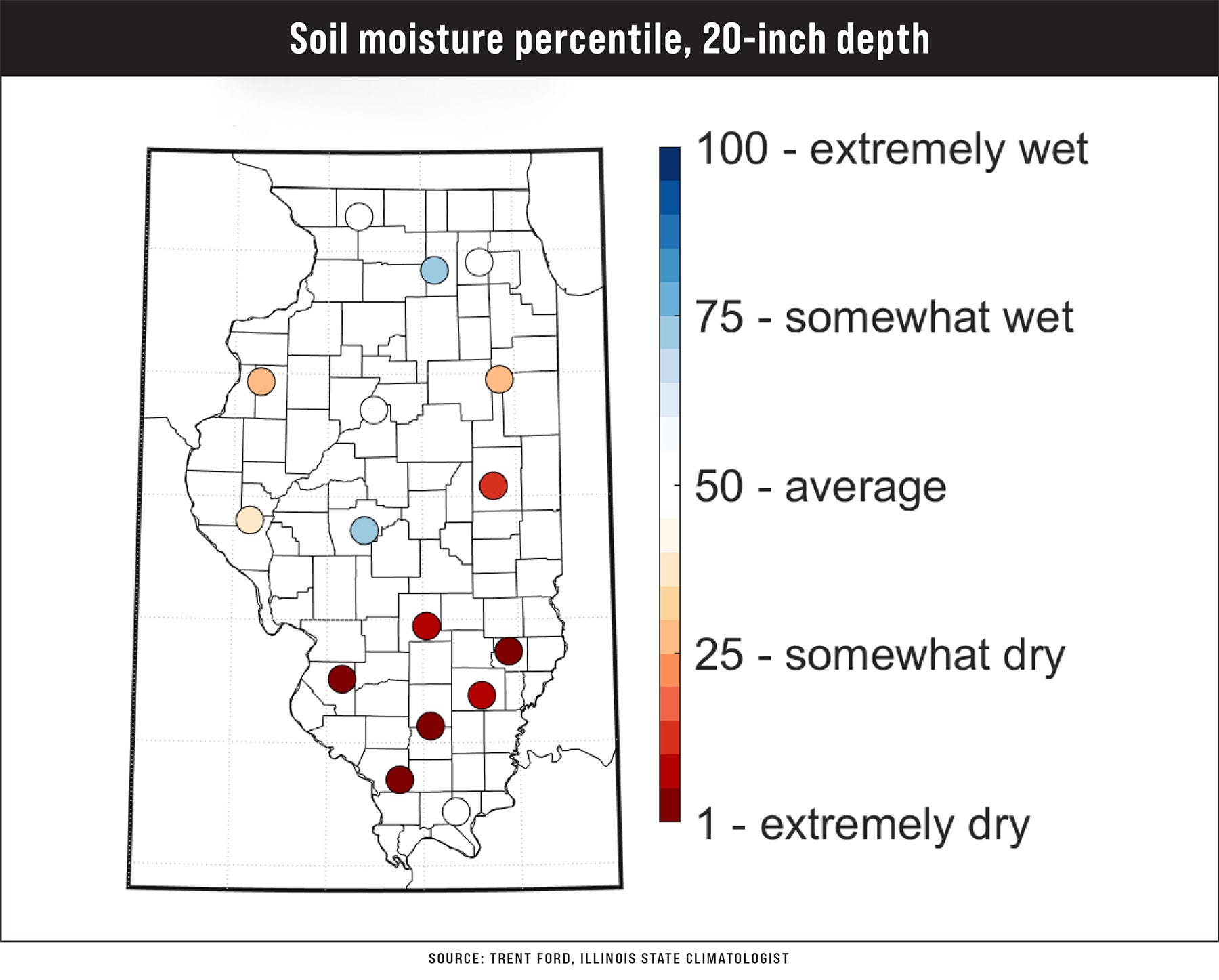

Illinois State Climatologist Trent Ford confirms that across parts of western Illinois and most of southern Illinois, particularly south of Interstate 70, conditions range from abnormally dry to severe drought. That means subsoil moisture levels are far below normal, too. Across southern Illinois, subsoil moisture levels all fall in the extremely dry range.

“Maybe 20 inches down, the water tables are pretty far below what they would normally be,” Ford says. “To fix that, we need four to five weeks of abundant precipitation that is soaking in.”

How much rain will it take?

In western Illinois, Ford says the Quincy area got 60% of the normal rainfall in 2023, which puts that area at 11 to 12 inches below normal. They need 11 to 12 inches of precipitation to absorb into the ground to get their soil moisture back to normal.

There’s a catch, of course: Drought areas need that quantity of rain, but they need it slow and easy so it can soak in, on unfrozen ground. Winter complicates that.

“It’d be hard to imagine getting enough rain in the style that we want to be able to do that. We’re talking about needing wetter-than-normal weather over the next three months, just to start to make a dent in it,” Ford explains.

As any livestock producer can testify, soils are not frozen on top. That means the top 4 to 8 inches can become very wet; then a heavy rain or heavy snow that melts quickly won’t soak in effectively.

“So, in many places, we’re seeing wet soils on top of very dry soils, and we need that to be rebalanced,” Ford says. But it also takes time and consistent rains or snows to get water from the top 8 inches down 50 to 60 inches into the soil.

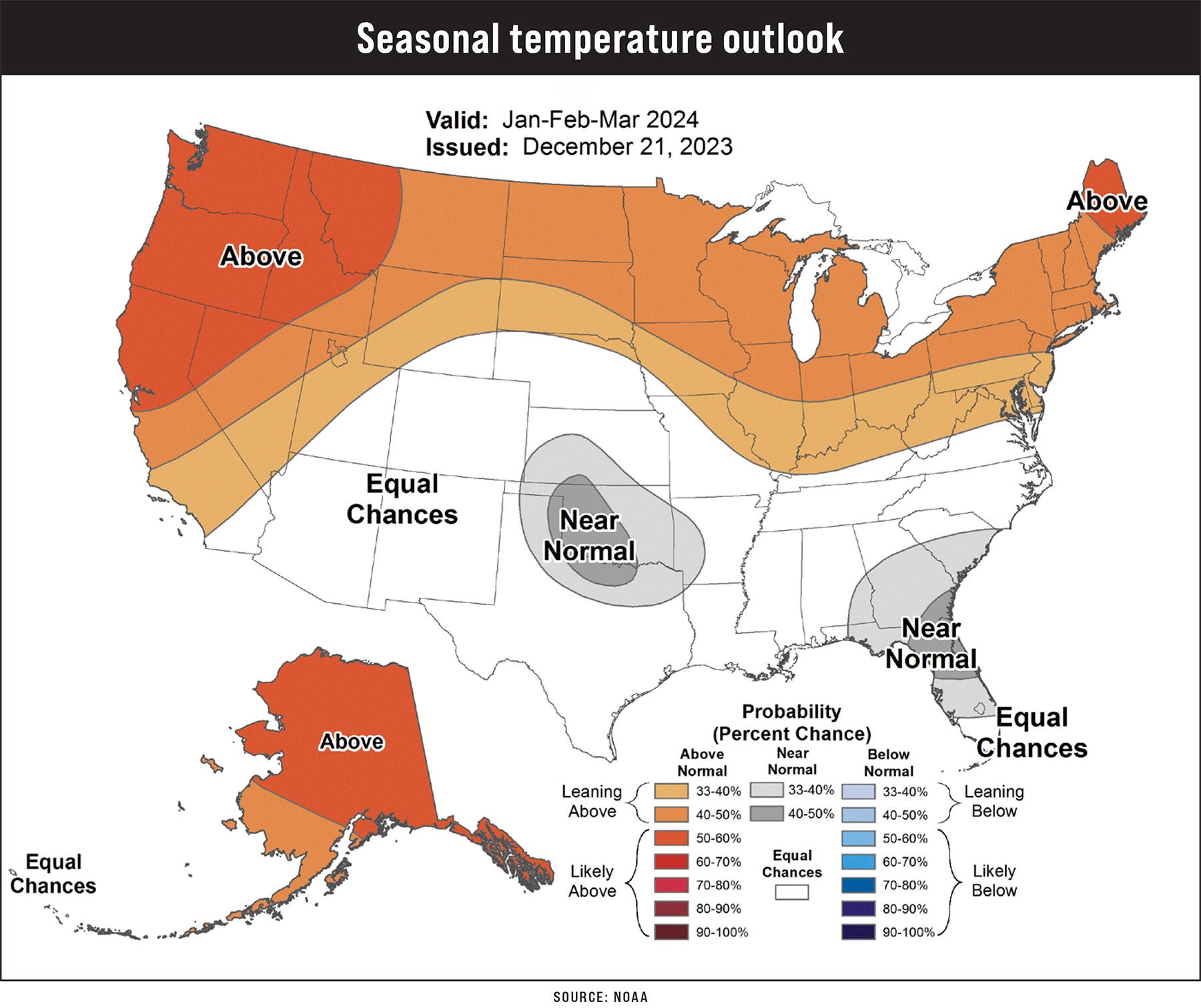

Temperature complicates that picture, including the frigid air system that’s moving into the Midwest this weekend.

“That’s going to freeze that topsoil very quickly, so any rain on top is not going to be all that beneficial,” Ford explains.

Next 3 months

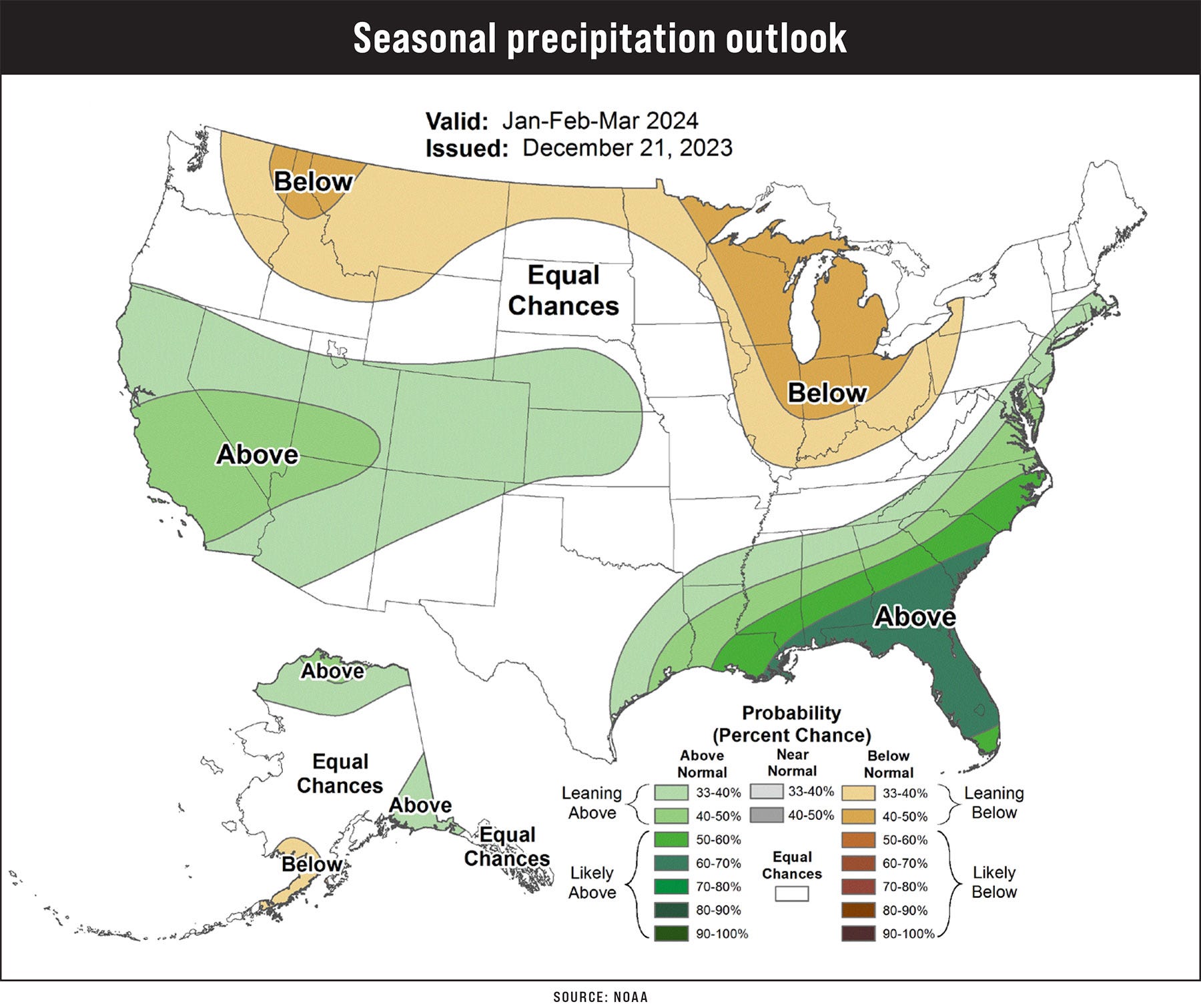

Ford says what Illinois soils really need is an active jet stream pattern over the next three months, which would bring precipitation systems regularly between now and planting.

“Getting one of these systems every 10 days or two weeks is how we can really make a huge difference in eliminating the subsoil moisture deficits,” he adds.

The three-month outlook isn’t great, however. January, February and March outlooks are showing drier-than-normal conditions across much of Illinois and the Great Lakes region. The next two weeks show better chances of consistent precipitation, but that’s inconsistent with the overall outlook.

Ford is concerned about going into April and May with these deficits. Dry weather is good for planting, but if rain doesn’t arrive after, plants won’t be able to find much moisture deep in the soil. But that’s also what happened in 2023 in many parts of the state, when rain didn’t come until late June, July and August.

“It doesn’t really matter how deep your water tables are if you’re getting the rain you need,” Ford says. “The problem is if the rain doesn’t arrive, then you’re banking on subsoil moisture that isn’t there.”

Changing weather patterns

Ford says Illinois has experienced its share of climate change. While it doesn’t make sense in the context of this story, the overall climate for the state has gotten warmer and wetter over the last 100 to 150 years. Overall, winter has warmed faster than the other seasons, and we no longer get consistent cold air throughout the winter.

“We get bursts, like in 2022 at Christmastime, and like what’s coming this weekend, but it doesn’t happen as often or stay around as long,” Ford explains.

Soils used to freeze and stay frozen for a while, but they don’t as often anymore, as many farmers will attest. It’s a continual freeze-thaw-freeze-thaw cycle throughout the winter.

“We’re also getting wetter overall,” he adds. Even though Quincy had its third-driest year on record, the long-term trend is that it’s gotten wetter overall since the late 1800s.

The other trend is in how the rainfall now comes: fewer large rains of 2, 3 and 4 inches, followed by periods without any rainfall, especially in summer.

“We have more periods of drought impacts despite that wetter trend,” Ford says, adding that the changes have some benefits, including a longer growing season.

That’s exactly what many farmers have seen the past two years, where every single month in the growing season was drier than normal, except July and August.

“We’ve had two years now where we’ve accumulated pretty significant rainfall deficits during the growing season, but we got enough rain when we need it the most for the crops to get by,” Ford says. He notes that 2023 is the driest year on record since 2012.

And, as Ford adds, agriculture can work that way — but it’s a lot riskier.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like