January 26, 2024

At a Glance

- Lack of measurability, unfair pricing, long-term contracts and additionality are reasons farmers avoid carbon offset market.

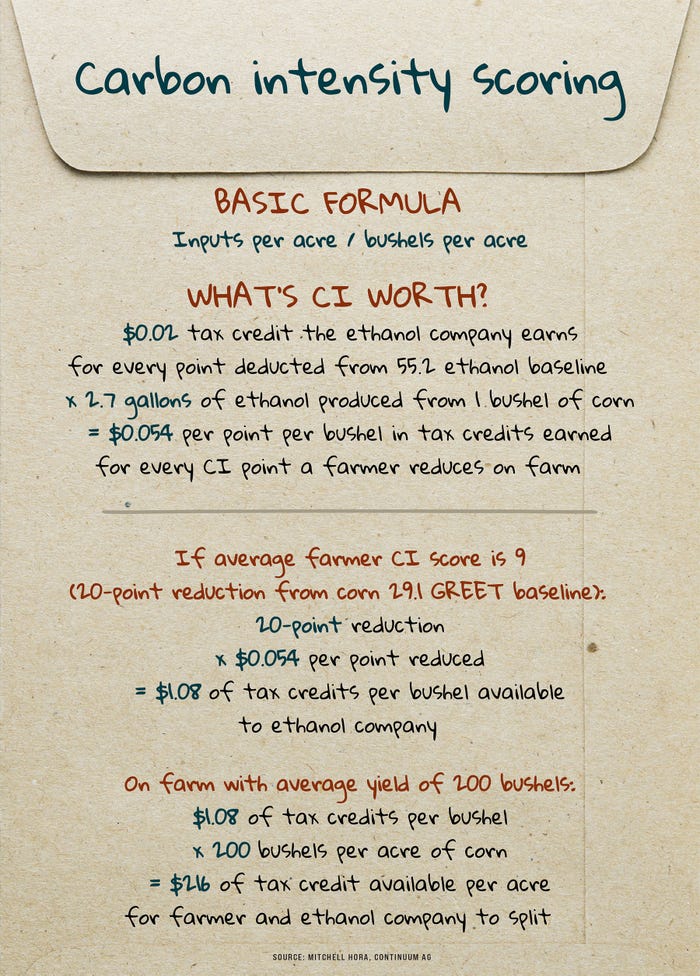

- To be compensated for carbon, farmers need to know their carbon intensity score, which measures carbon footprint per bushel.

- The driving force behind CI score compensation is the 45Z tax credit for creating low-carbon renewable biofuels.

On the Carroll Family Farm in Carthage, Ill., being a good steward of the land isn’t a new concept. The Carrolls have raised corn, soybeans and pigs for five generations and counting, implementing conservation practices for decades.

When John Carroll first heard rumblings of farmers getting paid for conservation via the carbon market, he was intrigued but skeptical.

“I was reading and hearing all this discussion around sustainability,” Carroll says. “But nobody really knew exactly what that meant, how to measure it, or how to compensate for it.”

Like a lot of farmers, Carroll quickly realized there were problems with the voluntary carbon offset market. His biggest objections were the lack of measurability, unfair pricing, long-term contracts and additionality — meaning he and many other conservation-minded farmers wouldn’t be compensated for their decades of conservation work, only for new practices.

“My first reaction was that it all sounded good, but I was a long way from being onboard,” Carroll says. “I had a lot of questions before signing my land up to a 10-year commitment with a startup that claimed to pay us $10 per acre and do a good job.”

When Carroll met Mitchell Hora, everything changed.

Carbon intensity

“What’s happening now is so different than what we’ve seen the last five years — and it’s so much better,” says Mitchell Hora, a seventh-generation farmer from Washington, Iowa. “It could be a game-changer for family farms and American ag.”

Hora founded Continuum Ag in 2015 to help farmers profit from improved soil health. He says what farmers really need to know for 2024 is their carbon intensity score, or CI score. A CI score measures the carbon footprint per bushel of grain produced. In contrast with voluntary carbon offset markets, where carbon is sold to the left and grain is sold to the right, CI scoring allows carbon and grain to be sold as one asset, remaining together through the supply chain.

“The game is changing,” Hora explains. “There are no carbon schemes. It is simply a company quantifying its carbon footprint.”

SCORING: “Using a company to help you measure and track carbon is kind of like buying an option — and it’s a pretty cheap option given the potential upside,” says John Carroll of Carroll Family Farms in Carthage, Ill.

The driving force behind CI score compensation is an amendment to the Inflation Reduction Act, called the 45Z tax credit. The amendment states companies can receive tax credits for creating low-carbon renewable biofuels like ethanol, biodiesel, renewable diesel and sustainable aviation fuel.

The U.S. Department of Energy developed the Greenhouse Gases, Regulated Emissions and Energy Use in Transportation, or GREET, model to quantify the carbon footprint across biofuel supply chains. The GREET model creates a uniform scoreboard to track carbon emissions, and a transparent pricing system to reward CI point reductions. CI scoring is also not based off additionality, but rather on how companies and farmers compare to those around them.

Biofuels companies can take advantage of the 45Z tax credit by reducing their Scope 1, Scope 2 or Scope 3 emissions.

Scope 1 emissions are direct from facilities and can be reduced by building a carbon dioxide pipeline or other methods of carbon capture and storage.

Scope 2 emissions are indirect from energy sources and can be reduced by investing in renewable energy or energy efficiency.

Scope 3 emissions are indirect emissions from the supply chain. These are where farmers can benefit by improving the carbon footprint of their grain.

“Biofuels companies need this number to earn tax credits — and it means very real money for farmers,” Hora says.

U.S. ethanol has a CI score of 55.2, or 55.2 grams of greenhouse gas per megajoule. Corn has a typical CI score of 29.1, meaning that according to the GREET model, corn is responsible for over 50% of the carbon footprint in a gallon of ethanol.

Hora and his team at Continuum Ag are helping farmers develop their own CI scores by calculating inputs per acre divided by bushels per acre. Their average farmer customer has a CI score of 9 — a whopping 20 points below the GREET model.

Hora’s own CI score is a minus 4, thanks to his nutrient use efficiency, use of cover crops and no-till, and 212-bushel-per-acre corn yields. Some of his farmer customers, he adds, have had CI scores as low as minus 15.

“Today the U.S. Department of Energy says farmers are more than half of the problem, but our numbers show farmers are a huge part of the solution,” Hora says. “Ag has an amazing story to tell of being sustainable and not only reducing our carbon footprint, but in many cases, being carbon negative.”

How CI score works

Getting paid for carbon at the farm level boils down to data collection and management. Every field has a different CI score, and every county has a projected CI average. When a farmer sells corn to the elevator or ethanol plant, their bushels would be linked to their CI score. If their CI score is less than the county baseline, the elevator or ethanol plant would pay the farmer a premium on each bushel of grain sold. The further from 29.1 a farmer can score, the better.

“There’s a huge financial opportunity for our rural communities here,” Hora says. “With over 6 billion bushels of corn going into ethanol production, it’s a chance to showcase how farmers can help be part of a sustainable future for U.S. energy independence.”

Early calculations suggest Continuum Ag’s average farmer score of 9 could be worth over $200 per acre. With Hora’s own minus 4 CI score, the suggested value doubles to over $400 per acre.

The kicker? Nobody knows what the farmer will earn and what the ethanol company will earn. Because the tax credit doesn’t begin until Jan. 1, 2025, the IRS hasn’t released its final guidance.

The other kicker: Biofuels produced in 2025 are manufactured with the 2024 crop. The 2024 crop has a carbon footprint influenced by practices done in fall of 2023.

That means if you’re a farmer who’s interested, you need to take action now to get compensated later.

The 45Z tax credit is due to end in 2027, so premiums may only last a few growing seasons. However, Hora is optimistic CI participation will ignite similar programs available for both grain and livestock producers.

“The key here is it cannot end up being farmers versus biofuel,” Hora says. “We must communicate and raise awareness about the program. There’s plenty of money here to go around for everyone to make significant upside.”

Hora says collaboration is key for the 45Z tax credit to be successful — collaboration among farmers, biofuels companies and the federal government.

“This is just where the puck is going, and I want to make sure farmers are aware and in position to capitalize on it,” he says. “Do we want to get ahead of this while we have a carrot, or are we going to wait until it’s a stick?”

In Illinois, he adds, farmers seem to be more skeptical of government intervention and biofuel partnerships than surrounding states.

“Government corruption and mismanagement at the state level influence farmer mistrust at the federal level,” Hora says. “Farmers have been burned in the past by empty promises, so they’re understandably cynical. But this is a legitimate opportunity that we need to pay attention to.”

Hora recommends three steps for farmers to capitalize on CI compensation:

Create awareness by asking the nearest elevator or ethanol plant about CI and 45Z opportunities and potential pilot programs.

Create visibility by developing a CI score for each acre. Hora and his team at Continuum Ag have software to help farmers develop their own CI score at topsoil.ag for $5 per acre.

Take control by documenting farm data, decide how to monetize the farm data, and consider how additional conservation measures could impact future CI scores.

COLLABORATION: “Farmers need to start talking with the ethanol companies, and ethanol companies need to start talking with farmers,” Mitchell Hora says. “We have to collaborate and create more awareness about how big of a deal this is for farmers.”

Farming carbon

Today Carroll has a CI score on every acre he farms. Continuum Ag calculated his average CI score at a 0 due to his high yields, cover crops, tillage practices and use of manure.

Carroll says CI score has influenced the speed of adoption of certain practices, but there aren’t any conservation measures he’s added solely because of CI scoring. “Everything we’ve implemented, we’ve done because we believe in the economic and agronomic value added to the farm,” he says.

One of his main frustrations so far with CI scoring is the complexity of the program.

“Our No. 1 values are simplicity and efficiency, and this does not feel like it’s going to be simple and efficient,” Carroll says. “I think there will be a number of farmers who aren’t interested because they don’t have the manpower for the paperwork and bureaucratic element.”

Still, Carroll remains skeptical yet optimistic of carbon compensation potential at the farm level.

“I have no idea whether this is really going to turn out to be valuable, but it certainly feels like we’re headed the CI score direction,” he says. “I expect early adopters to see some economic benefit from doing this; then in five or 10 years, it will just become the norm.”

Tracking carbon at the farm level is inevitable, Hora adds. It’s up to farmers to decide how to position themselves to capitalize on carbon opportunities.

“This is going to happen whether you like it or not,” Hora says. “Your corn is going to have a score on it whether you like it or not. Do you want to be part of the solution and get paid for it? Or are you going to sit on the sidelines and let your neighbors get paid?”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like