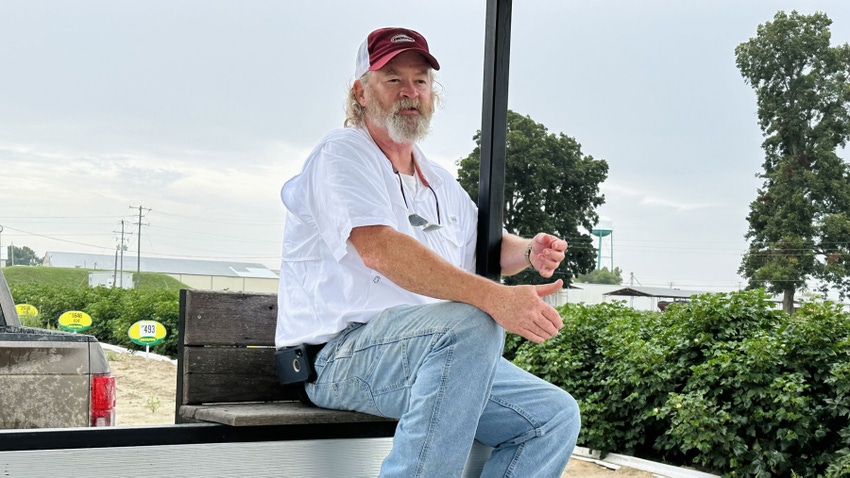

In 2023, growing conditions for cotton were near perfect in Scott, Miss., and the season also resented a phenomenal opportunity for Jay Mahaffey, science fellow at Bayer Crop Science and manager of the Scott Learning Center, to dive into research never attempted.

His plan was to test both old and new cotton varieties to get to the root – or better yet the boll of factors leading to improved production over the last 25 years. Through a study he coined, Antique Alley, Mahaffey set out to discover, “What has changed in cotton production?”

Mahaffey gave the premise of the study. He said, “We know for a fact that cotton yield has gone up Beltwide in the last 25 years. From 1995 to 2020, yield increased 57.8% according to unbiased numbers from the USDA. Fiber quality is notably better, and turnout is up 6% in my career. The question is, why is it different?”

Groundbreaking discoveries in cotton breeding, biotechnology, agronomic management, plant growth regulator (PGR) use, and seeding rates have all contributed to the continuum of production during this timeframe. Furthermore, the boll weevil has been eradicated, and novel biotech offerings have reduced the threats from cotton bollworms, lygus bugs, thrips and tobacco budworms.

“Cotton production is a whole different system today,” Mahaffey said. “The debate about why all of that happened is the fun part of this study.”

Antique Alley makes history

The idea of Antique Alley was born when Mahaffey came across seven older varieties of cotton seed, all from Deltapine lines. These older varieties had an average Plant Variety Protection (PVP) certification of 1995 and included revered products like Deltapine 5415, Sure-Grow 125, and Sure-Grow 501.

Mahaffey was thrilled to have come across these varieties, and it gave him opportunity to approach this academic question from an industry standpoint.

To test their performance in today’s growing conditions against current technology, he planted the antique varieties alongside seven newer varieties with an average PVP date, or patent date, of 2020.

The two eras of cotton seed development were further divided into two more management groups, totaling four systems spanning 25 years of cotton production improvements in both breeding and management. The four systems included: old varieties without PGR, old varieties aggressively managed with PGR, new varieties without PGR, and new varieties aggressively managed with PGR.

Mahaffey managed the cotton plots, noting the excellent growing conditions in 2023, favorable of achieving very high yield, with no boll rot and very little target spot or foliar disease. Insect pests were sprayed at threshold in all treatments.

The season proved successful, and data was collected at harvest with an apparatus designed by Mahaffey that he calls the Boll-O-Meter. This specialized tool allows the collection of harvestable cotton bolls with the intent of positional mapping and evaluation of fruit accumulation patterns in the various treatments.

Mahaffey said the idea goes back to a study from 1995, widely known in the cotton industry, Useful Tools in Managing Cotton Production: End of Season Plant Maps by research agronomist, Jack McCarty and research geneticist, Johnnie Jenkins both at the USDA Agricultural Research Service crop science research laboratory.

This Mississippi State University publication is most notably recognized by its cover illustration – the “cotton tree” – depicting the dollar value of individual cotton bolls according to their position on the plant.

Mahaffey said, “It was sort of the first public discussion of the positional mapping technique, and it as the basis used to generate and evaluate the data in Antique Alley. Positional mapping is labor intensive, but it is the only way you can fully document yield accumulation in cotton. The Boll-O-Meter tool made it much easier to do this sort of research.”

25 years of cotton data evaluated

Sifting through the data from Antique Alley took months. At the time of the interview, Mahaffey had measured three primary parameters noting there is still much to unpack and discover from the results.

"It’s the coolest thing I have ever gotten my hands on,” Mahaffey said with a big smile. “It is absolutely the most marvelous thing.”

Data was analyzed to evaluate the most extreme comparison, the older varieties without PGR and the newer varieties aggressively managed. Mahaffey calculated the pounds per acre of cotton by fruiting position for each group, which provided confirmation of the yield potential gained across the entire system.

Results indicated a system gain of 68.2% or 779 pounds per acre, going from 1,142 pounds in the older untreated varieties to 1,921 pounds in the newer aggressively managed varieties. These results, Mahaffey noted, align with the 60 to 70% yield increase we have seen in unbiased statistics over the last 25 years.

However, when Mahaffey looked at the positional mapping, he noticed the distribution of fruit on the cotton plants was roughly the same across the entire field of treatments, no matter the era or management of the varieties. From there, he determined the yield increase was primarily related to the increase in sympodial bolls, or fruiting bolls on the cotton plant.

Across the replicated treatments, the likelihood of having a first position harvestable sympodial boll increased by 21% from the old untreated to the new aggressively managed varieties. The same trend was seen in second and third position harvestable bolls, with a 13% and 6.4% increase respectively.

In all, Mahaffey documented 185,000 boll increase per acre from the old untreated to the new aggressively managed cotton varieties, a whopping 56% increase. Not only are there more bolls, but they weighed more. Lint percent increased on average, systemwide by 6%. So, what does that mean in terms of value?

Mahaffey took the current loan price of around 56 cents per pound combined with the boll weight per position, to calculate the gross income potential. The result was a $438.43 per acre increase to the grower, not accounting for discounts or equity associated with fiber quality.

Cotton tree redefined

In the end, Antique Alley will be used to redefine the iconic “cotton tree” from the cover of the 1995 study. Mahaffey said, “What we wound up with is a new, revised version of the cotton tree, and it will e in our final publication.”

This research outcome is huge for the cotton industry, and Mahaffey said the data goes much deeper. In short, he said, this is a confluence of good science.

So how has cotton production changed in 25 years?

“Essentially, we have made a better energy factory, with a cotton plant that can set more fruit, support more fruit, thereby it sets a bigger crop which weighs more,” Mahaffey said. “It has also driven a change in agronomic management to control the crop the best way we know how with PGRs.”

As cotton farmers turn to the latest varieties, Mahaffey emphasized the importance of PGR management.

“Since cotton plants now make more energy, we must oftentimes help the plant in directing that energy to reproduction rather than growing a bigger plant. PGR management helps optimize the return on investment for growers when they use the latest varieties with new technology in a production system.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like