Georgia has 151 counties with federally listed endangered species. It has eight counties that don’t have an endangered species within its border. Most Southern states are similar, with many counties home to an endangered species. It may be a plant, insect, fish or mammal, but it’s something, and it’s there.

The Endangered Species Act was born in 1973. A good year, and not a bad act. It provides a framework to conserve and protect endangered and threatened species and their habitats. The act has been the vehicle to do some good things and protects some good species.

Conservation groups often go after EPA. That’s nothing new. But recent court decisions and policitacl shifts have given well-heeled conservation and environmental groups more fodder and powder to go harder after the agency, particularly how the agency reviews and determines how a chemistry may impact a federally endangered species. The argument is the agency has not maintained the spirit of Section 7 of the ESA. Called the ‘Interagency Cooperation,” Section 7 is the mechanism to ensure the actions federal agencies take, including those they fund or authorize, do not jeopardize the continued existence of any listed endangered species.

The stage is set for conservation groups to fire more holes into the process and how pesticides are regulated and used, or not used, including ones important to agriculture.

Some essential agricultural products for the Southeast, just like the rest of the nation, include endangered species buffer zones to help keep the product on target and away from natural areas and endangered species, and applicators are required by law to follow them.

ESA Buffer Zones

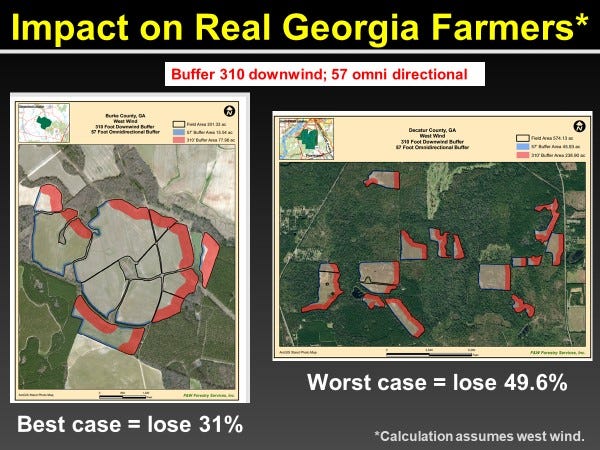

During the annual Southeast Fruit and Vegetable Conference in January, Stanley Culpepper, UGA Extension weed specialist, provided an example of how recently labeled ESA buffer requirements for an important herbicide would affect the percentage of acres the herbicide could legally be applied on a real-life Georgia farm. The buffers included a 310-foot down-wind buffer and a 57-foot omnidirectional buffer zone from wood lines. For a larger field on the farm, the herbicide could not be applied to a third of the acres around the field’s edge. For a group of smaller fields on the farm, the herbicide could not be applied on as much as 50% of the fields’ acreage. That’s not sustainable agriculture.

The door is open now and forcing EPA to reexamine its decision process and buffer requirements for about 1,100 active ingredients.

Conservation groups acknowledge many species are endangered due to urban sprawl and lost habitat. But is anyone going to tell a homeowner to tear the house down or take a condo down? Likely not, but regulators can extend the ESA buffer zones, and that may make less of a farm legally available to apply the essential products needed to make sustainable decision for that farm. That’s bad.

Whether in front of the scene or behind it, reasoned heads must make rational decisions as the slippery slope of legal actions breathes new life into the Endangered Species Act.

Actions to Watch

On Jan. 6, the Center for Biological Diversity filed a formal notice of intent to sue the EPA for approving more than 300 pyrethroid products, the center says, “without considering their harm to endangered plants and animals.”

On Jan. 14, the EPA released a statement reversing decades of practices, saying it is now taking further actions to comply with the ESA when evaluating and registering new pesticide active ingredients. Moving forward, when EPA registers any new conventional active ingredients, it will evaluate the potential effects of the AI on federally threatened or endangered species, and their designated habitats. In the statement, the agency said in the past it ‘did not consistently assess the potential effects of conventional pesticides on listed species when registering new AIs.’

Earlier this month, a federal interagency working group, which includes EPA and USDA, announced it will hold a public listening session on Jan. 27 to hear stakeholder viewpoints on ways to improve the ESA Section 7.

On Jan. 11, EPA renewed Enlist Duo and Enlist One herbicides registrations for seven years but with an ESA qualification. EPA determined the uses of Enlist Duo and Enlist One “are likely to adversely affect listed species but will not lead to jeopardy of listed species or to the destruction or adverse modification of designated critical habitats.” However, EPA will prohibit the use of Enlist Duo and Enlist One in counties where EPA identified risks to on-field listed species that use corn, cotton or soybean fields for diet or habitat. According to EPA, the counties where use will be prohibited by these new measures represents approximately 3% of corn acres, 8% of cotton acres, and 2% of soybean acres nationally.

In November, U.S. Senator Cory Booker (D-NJ) introduced the Protect America’s Children from Toxic Pesticides Act of 2021, specifically to change the current Federal Insecticide, Fungicide and Rodenticide Act of 1972, including banning organophosphate and neonicotinoid insecticides, and paraquat. The act would also allow local communities to enact protective legislation and other policies without being vetoed or preempted by state law. And if passed would suspend the use of pesticides deemed unsafe by the E.U. or Canada until they are ‘thoroughly reviewed’ by the EPA.

Read more about:

Endangered SpeciesAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like