By Ilena Peng, Michael Hirtzer and Will Wade

For Stuart Woolf, who grows wine grapes, almonds and other specialty crops in California, solar power is a necessary compromise as farming gets more challenging.

Woolf, who has 1,200 acres of panels on his farm in the state’s Central Valley, says individual growers like him are turning to solar to survive. He began leasing land to solar developers about a decade ago, an arrangement that provides him with a much-needed new profit stream.

“We would prefer not to have any solar, but if we don’t have it, we won’t have the ability to keep this farm going,” he said.

Farmers are increasingly embracing solar as a buffer against volatile crop prices and rising expenses. Their incomes are heading for a 26% slide this year, the biggest drop since 2006, as cash receipts for corn, soy and sugar cane are expected to drop by double-digit percentages.

The shift is a big part of the renewables push in the US: The American Farmland Trust estimates that 83% of expected future solar development will take place on agricultural soil.

“Solar developers are looking for larger parcels of flatter land, and agricultural land often features those characteristics,” said Sean Gallagher, senior vice president of policy for Washington, D.C.-based trade group Solar Energy Industries Association. In return, farmers get more stable revenue over the long term — and it can be above what they earn from crops, he said.

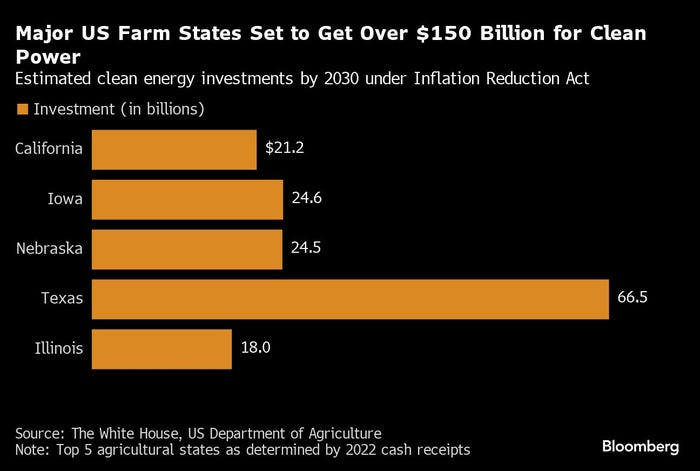

The movement is certain to get a kick from President Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act, which has helped accelerate the clean energy boom through tax incentives for solar developers. The country’s five largest agricultural states are among the biggest beneficiaries, poised to receive about $155 billion in clean power investments by 2030.

The IRA has already attracted a total of more than $110 billion in clean energy investments in the first year since it was signed in August 2022, with more than $10 billion funneled toward solar manufacturing.

Because renewable energy can be costly to set up, some farmers are leasing their land to developers, who typically cover installation expenses and own the generated electricity. Others have installed their own panels, selling the energy back to the grid to offset the costs of powering their farm.

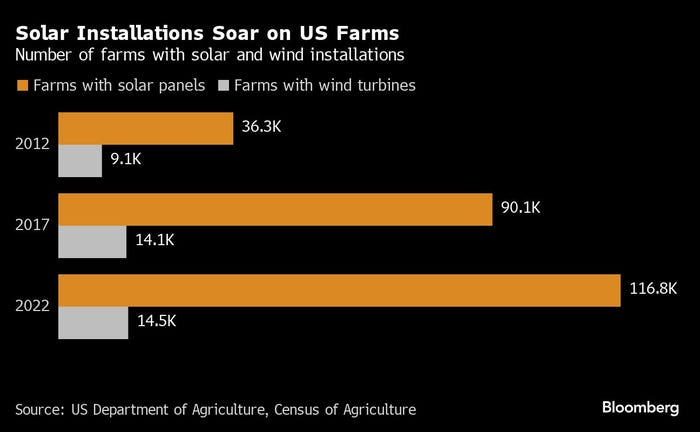

More than 116,000 farms had solar panels in 2022, a 30% jump from five years prior, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture census released last month.

Some farmers worry that the trend will accelerate a shrinking of farm fields. The U.S. has already lost about 20 million acres of agricultural land — an area nearly the size of Indiana — from 2017 to 2022, according to the USDA census. That has been driven in part by an aging farmer population and higher production costs that make it more difficult for younger generations to farm.

Solar panels are “covering up so much of the most fertile, productive farmland in the world,” said Ben Riensche, an Iowa corn and soybean farmer. “Someday, people will have electricity to run their Tesla, but no food.”

Others don’t see it as a food-versus-fuel debate. “There’s plenty of acres and record supplies. I don’t think we need those corn acres,” Dan French, executive producer of Solar Farm Summit, said at a conference held outside of Chicago.

Solar so far makes up a small share of overall U.S. farmland. Having solar account for as much as 40% of US electricity would require about 5.7 million acres, the Department of Energy estimates. That is less than 1% of America’s some 880 million acres of farmland.

Significant Impact

But farmers are concerned that even small losses will have a significant impact. In Louisiana, cropland is more limited than in the Midwest or Plains regions, said Jim Simon, the general manager of the American Sugar Cane League.

“We farm on ridges next to the bayou,” Simon said. “When that ground is taken up, there’s nowhere else you can go to find that acreage.”

Solar can be good or bad depending on how it plays out in a given area, according to Nathan L’Etoile, a managing director at the American Farmland Trust, a non-profit focused on preserving agricultural land.

He estimates that landowners could get $1,200 per acre annually in a solar lease. Meanwhile, lackluster crop markets mean farmers are estimated to lose more than $100 per acre planting corn in Illinois, according to the University of Illinois.

Woolf believes solar development should be taking place on the least-productive land, but as farms have to determine what’s best for their businesses it’s leading to a “checkerboard kind of pattern of solar development covering up really great farmland.”

Still, he has plans to triple the amount of solar on his land — covering about 15% of the total acreage — as panels offer a kind of insurance to the farming business.

“We just look at it as almost another crop that allows the rest of it to continue to grow and prosper,” he said.

© 2024 Bloomberg L.P.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like