Farmers following USDA World Agricultural Supply And Demand reports normally focus on the agency’s forecasts for U.S. crops. But when the government prints its last update for the calendar year in December, the growing season here is already over, and no revisions to production are typically made for corn and soybeans until the final monthly numbers come out in January.

USDA followed that tradition in its Dec. 8 WASDE. It was hardly surprising traders turned their attention to the southern hemisphere, specifically soybeans in Brazil, where a long harvest season will kick off in coming weeks. The size of that crop should be one of two key factors holding the keys to rallies into 2024.

The average trade guess ahead of the Dec, 8 release believed USDA would trim its forecast mostly in line with the estimate put out by Brazil’s CONAB ag agency the day before, which lowered the crop by almost 2%, or 107 million bushels. As it turned out, USDA wasn’t quite so aggressive, but still cut 73.5 million bushels off its estimate.

While that’s not by itself enough to generate big price moves, it could trigger more buying of beans from the U.S. if end users want protection in case the market gears up for more moves this winter. And farm numbers weren’t the only data out Dec. 8 from Washington. The Labor Department woke up Wall Street with a surprisingly strong jobs report that sent the dollar higher – which could have its own major ramifications for commodity prices.

No U.S. changes

For the record, USDA kept its forecast for U.S. ending stocks and average cash prices unchanged at 245 million bushels and $12.90. But for soybean growers, the numbers raising eyebrows came from the agency’s expectations for U.S. exports. After cutting its forecast for sales in October to 1.755 billion bushels, USDA stayed with that estimate again last week, throwing cold water on an early surge from its Brazil numbers.

Less competition from Brazil would seem to give the U.S. a leg up on export business. A smaller U.S. crop and the slow start to the selling season previously convinced USDA to forecast total shipments for the 2023 marketing year down 12% from last year and 18% lower than two years ago.

Dry conditions in Brazil’s key center-west growing region show up clearly in Vegetation Health Index maps for Brazil. The soybean VHI for Brazil is 14% below average, falling to the lowest level for mid-December since 1985, when the country’s then-fledgling industry saw yields plunge more than 20% below normal. Current projections are nowhere near that bad, with USDA seeing them down around 7% from early expectations. But with rainfall forecast below average over the next two weeks at least, the jury is still out on just how the current dry spell will impact production.

Soybean pie share

Supplies out of the world’s three biggest exporters – Brazil, Argentina and the U.S. – figure into one of the ways I use to forecast export demand. The bigger the U.S. share of exportable supplies not used by crushers domestically, the larger the share of total world exports growers can expect.

But the size of global soybean trade, the other factor dictating U.S. exports, could stymie any attempt at a rebound in prices if global demand slows as projected.

China has been the big dog in the world market thanks to a growing population with more money to spend from a booming economy that helped its share of global export demand triple. Now that economic boom appears to be something of a bust. Not only is China’s economy sputtering seriously, but it’s no longer the world’s largest country as its people age due to the country's disastrous one-child policy.

Nonetheless, after robust buying of Brazil’s old crop supplies, USDA believes China will import 3.75 billion bushels of 2023 crop soybeans, up from its November estimate and more than 1% higher than 2022-2023. Whether that pace pans out, however, is a big question mark.

Many of those beans will help fatten hogs – the Chinese eat more than half the world’s pork supply, easily the most of any country.

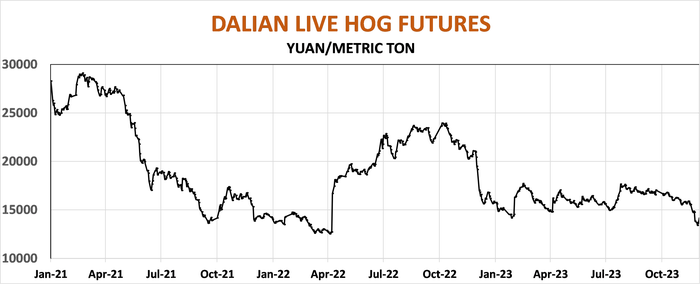

But the Chinese hog industry, like its banking and real estate sectors, is in tatters due to overproduction. Hog futures on its Dalian Commodity Exchange are down more than 25% since January, forcing some of its largest hog companies to sell off farms as they battle red ink and mounting debts. So unless those prospects enjoy an abrupt about-face, hopes for coattails that help the U.S. are in doubt, unless other countries, particularly China’s Asian neighbors, step up their game.

Trade slows

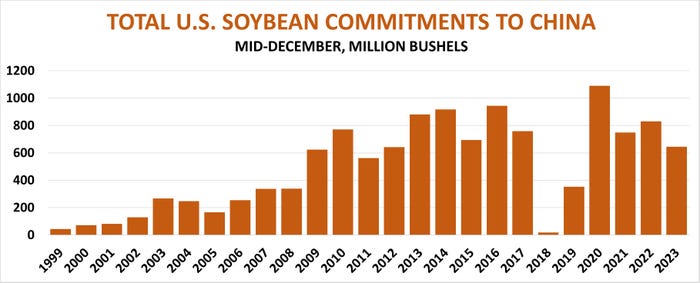

The other method I use to guess export potential comes from weekly sales data – who’s actually buying how much. This metric points to a major slowdown in sales and shipments to China. Accumulated commitments through November aren’t encouraging.

China took 28% fewer U.S. soybeans compared to the three-year average during the first quarter of the marketing year that began Sept. 1. That pace got a boost recently from a flurry of purchases after China signed its first trade deal since 2017, but slow early buying may be a hole exporters can’t overcome.

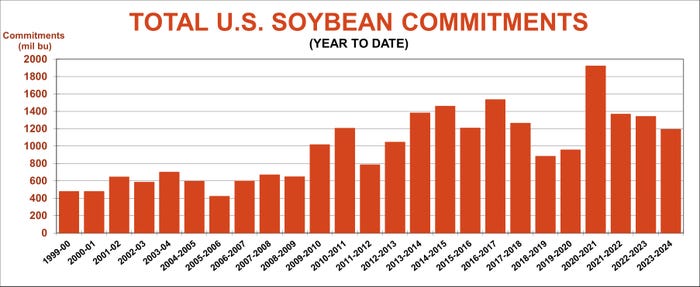

Still, overall sales and shipments to all customers tell a different story. While these too are down, they held up better than the China end of the business. Commitments to all countries suggest total exports for the marketing year could hit nearly 1.9 billion bushels, 7.5% more than USDA’s current estimate and enough to send U.S. ending stocks towards a bullish 100 million bushels if other categories don’t change.

Dollar surges

One other factor to watch is fallout from Friday’s jobs report, which showed greater than expected employment growth in November, along with a drop in the unemployment rate and stronger wage gains. That at least temporarily dashed hopes for an early cut in interest rates from the Federal Reserve.

Yields on U.S. Treasuries jumped, ending a two-month slide in the greenback because higher rates typically lure investors to a currency.

A cheaper dollar doesn’t boost U.S. ag exports, but can affect the price of commodities denominated in the greenback. Crude oil was already down to five month lows and wasn’t affected. But gold, which usually gains as an alternative to a cheaper dollar, broke sharply after notching an all-time intraday high Dec. 4.

Soybeans are a favorite of fund traders, and at times gain or lose from Wall Street turbulence, especially when big speculators face margin calls from leveraged bets and liquidate positions to raise cash. Funds were still long beans according to CFTC reports, holdings that could be vulnerable if financial markets melt down instead of continuing their “Santa Claus” rally.

Knorr writes from Chicago, Ill. Email him at [email protected].

Read more about:

BrazilAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like