If you like fast-paced action, the eight meetings to set monetary policy held each year by the Federal Reserve may not be must-see TV. The central bank’s Open Market Committee releases a brief statement, followed by the chairman’s press conference with financial journalists. Four times a year a “summary of economic projections,” or SEP, also comes out, along with “the dots,” plotted to detail participant’s forecasts for inflation, growth, unemployment and interest rates.

Most of the time Fed officials have telegraphed their intentions well beforehand to avoid surprising markets. The two-day meeting wrapping up March 20 has more drama than usual – and potentially significant impacts on farmers.

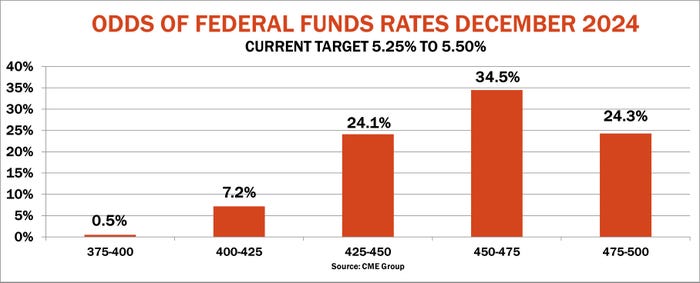

A year ago, markets expected a series of interest rates cuts, with the Fed’s benchmark short-term Federal Funds Rate falling near 4% this year and 3% in 2025. That would be good news for borrowers, who must contend with the current level of 5.375%. Investors believed the central bank would cut rates six times quickly to boost the economy as inflation fears disappeared and recession risks rose with tighter credit.

But a data barrage over the past few weeks turned this narrative on its tail. Signs of more “sticky” inflation, decent jobs numbers and a good economy could keep interest rates higher – and that could affect costs for everything from loans to grain storage and even farmland.

Inflation rises again

Fed officials remained silent after the latest readings came out on inflation, as they typically do during the “blackout” period leading up to meetings. That only adds to the uncertainty caused by February Consumer and Producer Price Indexes, which rose more than expected last week.

Of course, some of the fine print of these reports was contradictory, giving ammunition to both interest rate hawks and doves.

Adding to the drama: The average of the interest rate projections in the “dots” could rise if only two of the meeting’s 19 participants revise their forecasts, so it won’t take much to rewrite the headlines.

Odds for this jockeying change by the minute, as tracked by betting on Federal Funds Futures. This market’s ivory tower nearly universally expects the Fed to do nothing now, but trim rates by three quarters of a point or more by the end of the year, beginning in June.

Jobs stay strong

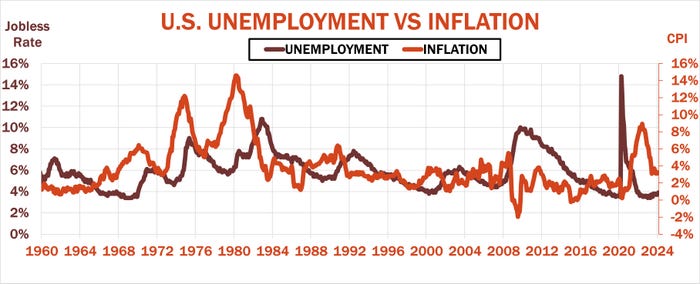

Controlling short-term interest rates is the Fed’s primary, but not only tool, to accomplish its dual mandate from Congress: Maximum employment and stable prices. The jobs part of that equation isn’t the problem. The unemployment rate stayed below 4% since January 2022, though it ticked higher to 3.9% in February despite strong jobs creation.

Inflation, as measured by the Consumer Price Index, has also come under control after rising to 8.9% in June 2022 when supply chains broke after pent-up demand emerged following the pandemic. But the downward path of prices ended at 3.1%, and ticked higher last month, with Producer Prices also rising.

The CPI, though best-known by the public, isn’t the Fed’s preferred measuring stick for inflation. That job falls to another report called PCE, or Personal Consumption Expenditures, which is reported later than the CPI. The PCE with food and energy stripped out fell to 2.8% last month but won’t come out again until a couple weeks after the Fed’s March meeting.

Dollar headwinds

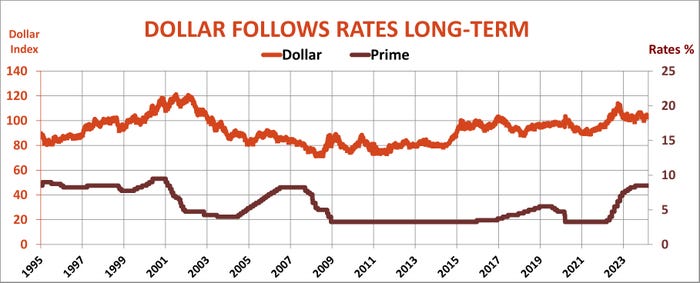

Uncertainty surrounding the Fed’s next move prompted some markets, including stocks, gold and Bitcoin, to sell off from record highs, part of the ripple effects that also include the value of the U.S. dollar. Currencies tend to follow interest rates, at least some of the time, because investors seek the highest risk-free returns. Ideas of falling U.S. rates caused the greenback to lose value last year, but that trend stopped when inflation began to stabilize.

The dollar’s value affects prices for some commodities, notably grains, gold and crude oil – a weaker currency increases the value of, say corn, when it’s priced in dollars on international markets. So, a stronger currency could be one more headwind for the grain market to overcome.

But that’s just one fallout to watch from the March 20 meeting at the central bank.

Fed fallout

Interest rates are, of course, the main focus, and any change would show up immediately in short-term rates, including those the CCC charges on commodity loans.

But rates on longer-term loans on everything from machinery to land could join the fallout depending on what Fed officials say, including their “dots.”

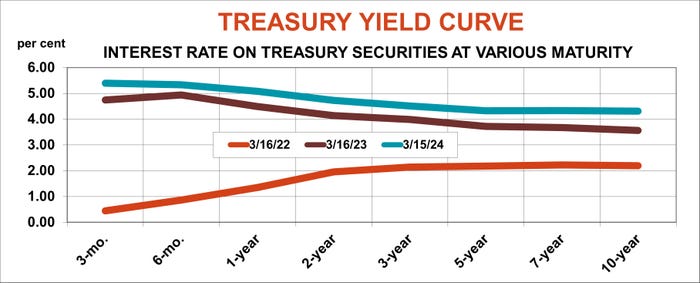

As normally happens when credit tightens, the yield curve on U.S. Treasuring is “inverted.” That is, rates for short-term debt are higher than those for longer duration as the market bets the higher rates won’t stick around for long.

Still, fears of rate hikes took the benchmark 10-Year Note near 5% last fall, though it fell below 4% in December and January before edging back to 4.3% last week.

This security is some times a peg for farmland loans, and it also can influence how investors value land because it’s the standard for risk-free alternatives that compete with land.

One question to ask with any investment is whether it’s a good value. For the 10-Year, one answer is the “equilibrium rate,” the Fed’s inflation expectation added to its “neutral” interest rate – the level that neither hurts or helps the economy.

The Fed says it’s long-term target for inflation is 2% while the neutral rate is also assumed to be 2%. Added together this suggests that fair value for the 10-year is 4%. My own forecasting models put fair value at 4.10% based on current conditions, and it could fall further if unemployment and inflation stay low and the economy and corporate earnings rise.

But if inflation or the assumed neutral interest rate rises, as some economists believe warranted, longer term rates could also move higher.

If you’re a farmer with funds to invest or don’t want investors bidding up prices of land on your shopping list, that might be good news. But for most growers, higher rates mean higher costs – and it doesn’t have to be the 1980s for that to hurt.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like