Stressful springs and reoccurring La Nina conditions gave growers good opportunities to price grain on weather rallies the last two years. But this narrative could be ready for a seismic shift in 2023.

To be sure, it’s early for planting, and parts of the Corn Belt face frost, drought and wet fields. Still, so far the bulk of the corn and soybean fields don’t appear to be facing imminent disaster.

Moreover, a shift in the pattern of ocean temperatures in the equatorial Pacific to El Nino warming significantly improves yield prospects after several disappointing harvests.

These developments don’t mean farmers should abandon hopes for rallies in coming weeks. But December corn charts are tilting bearish and November soybeans traded below $13 last week for the first time in April. Just as wildfire warnings cropped up in parts of the U.S., red flags also began flapping a bit in the grain trade.

Two questions are center stage: First, how will planting progress affect corn yields? And secondly, will El Nino conditions this summer increase potential for above average yields?

Yield drag risk

Bad spring weather can affect production by forcing growers to change acreage choices, though any impacts don’t show up in the data until the end of June or later. The real risk comes from delayed corn planting – soybeans appear affected only minimally by this.

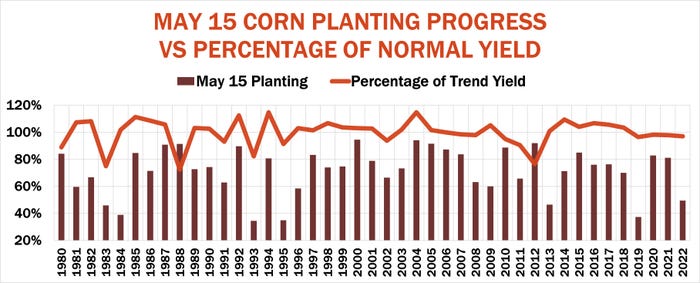

The metric used by traders to assess corn seeding speed is how much weekly Crop Progress reports from USDA show planted by May 15. On average over the past 35 years, 71% of corn is in by the middle of the month – 73% if only results from eight big states are factored in by their expected acreage. Both the date and those states matter because they’re key variables used in a model originally developed by USDA and since adapted by traders to forecast yields.

Farmers, of course, know the benefits of timely planting. But the impact on yields is mixed. While there is a correlation between planting speed and yields, it accounts for only 4% of the variance in yields. Part of this is because some years very fast planting end in drought, when farmers dusted in the crop and prayed for rains that never come.

Last year demonstrated the importance of planting speed. Just 49% of the crop was in by May 15, and that factor alone knocked almost four bushels per acre off yield potential. USDA as a result cut its forecast “normal” yield in the May World Agricultural Supply And Demand Estimates, which normally would be based on the higher, weather-adjusted number.

Last year wasn’t the slowest planting on record, but it did rank fifth on that tally since 1988. Similarly slow planting this spring would take USDA’s “normal” yield of 183.5 bpa down around 4 bpa again. And if planting lagged down to the 34% suffered by key states in the 1993 flood year, yield potential could drop below 177 bpa.

Warm summer?

By itself, planting speed is not enough to be statistically significant. But combined with other factors, including extreme June stress and July weather, explains some 94% of the variance in yields.

July rainfall has about the same impact as planting speed, and extreme June stress adjusts for years with drought-sped planting. But the most single important factor is July temperature, which accounts for 37% of yield variance, enough to be statistically significant on its own.

U.S. forecasters update their seasonal outlooks for summer weather April 20. The last guidance a month ago did call for heat from the southwest Plains into the eastern Midwest and South, but most of it wasn’t extreme. Some unofficial models are showing above average temperatures over most of the U.S., along with below average rainfall from eastern Illinois to western Nebraska, so the outlook remains uncertain.

El Nino returns

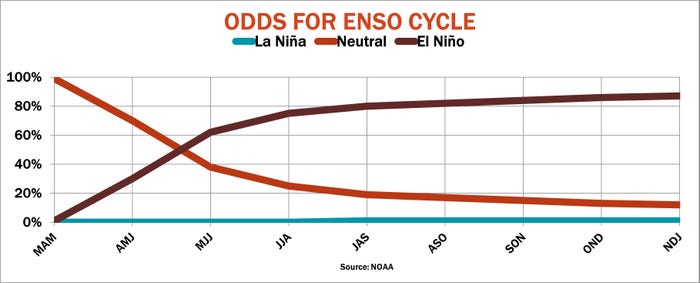

One influence on summer weather and upcoming forecasts is likely to be the shift in the El Nino/Southern Oscillation cycle. The latest forecast said the episode would begin in the May-July quarter, earlier than expected in March, and raised the June-August probability to 75%, though atmospheric conditions in the Pacific could still affect the onset.

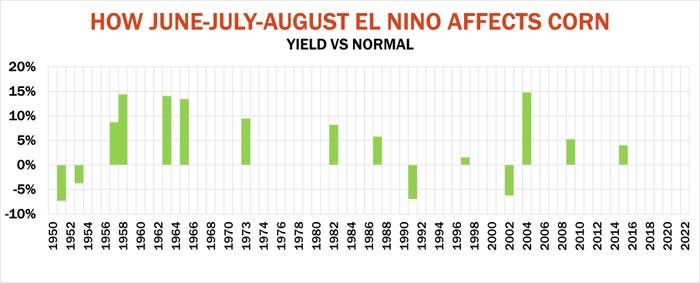

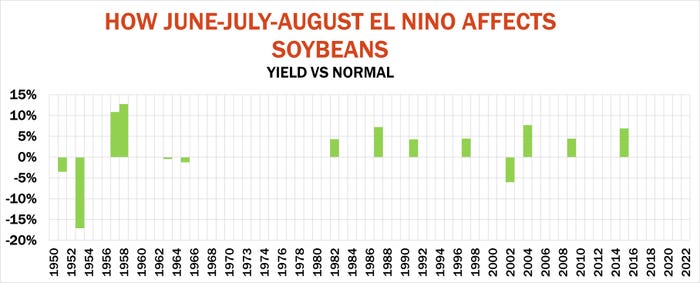

An El Nino summer doesn’t guarantee good yields, but it does make them more likely. Since ENSO data began in 1950, corn yields were above normal 73% of the time, with soybeans better 60% in years with El Nino summers. In those above normal years corn yields were ran 9% higher than expected, with soybeans up 7%.

A summer El Nino doesn’t rule out bad years – yields were less than 95% of normal three times, with soybeans suffering big losses twice. But odds favor decent crops because El Nino tends to brings normal temperatures and above normal precipitation to most of the growing region for the two crops.

Just like a dice roll, these are probabilities and far from a sure thing. Outside events from Wall Street, OPEC+, Ukraine, China or elsewhere could hatch into another Black Swan. But when betting on rallies for remaining 2022 inventory and expected 2023 production, knowing your tolerance for gambling is essential. Three-to-one odds may not sound like a longshot, but it could be a losing bet for your marketing plan.

.jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

Knorr writes from Chicago, Ill. Email him at [email protected].

The opinions of the author are not necessarily those of Farm Futures or Farm Progress.

Read more about:

WeatherAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like