There’s a reason U.S. farmers and crop merchants own some 25 billion bushels of storage, more than enough to hold expected domestic supplies of feed grains, soybeans and wheat this fall. Keeping those inventories off the market gives growers a chance to sell production after prices recover from seasonal weakness caused by the grain glut at harvest.

But making money from storage year-in and year-out takes more than just locking the bin doors and waiting. How you market your production – and indeed whether to store it at all – are just as important as pouring concrete and erecting sidewalls.

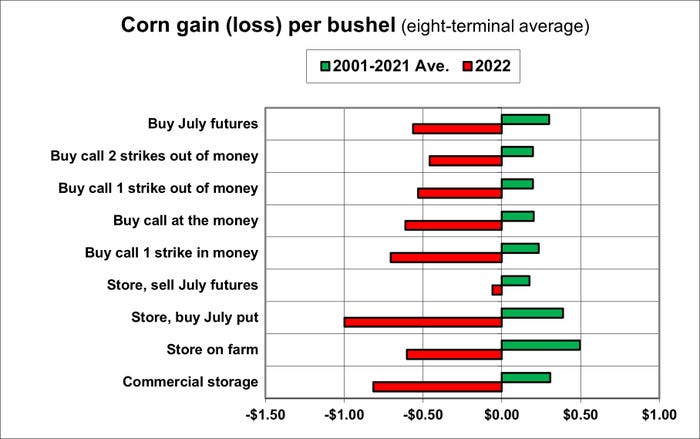

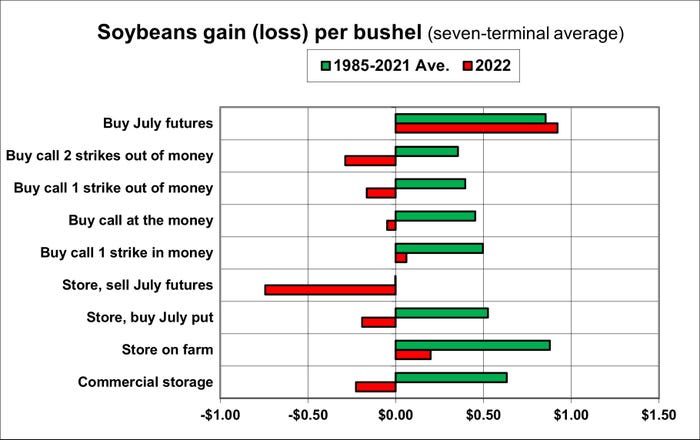

Producers who bet big on storing 2022 corn found out the hard way. Whether they kept production on farm, hauled it to town or used futures or options as hedges, the results left them worse off than just selling out of the field. Ignoring key warning signs made storage a loser, and soybean growers didn’t fare much better, according to Farm Futures long-term study of storage strategies. Even techniques with proven histories failed to measure up.

Alarms are already sounding about the outlook for 2023-2024. So here’s a look at what worked last year – and mostly didn’t – as you get ready to spin the wheel of storage fortune again.

The Farm Futures study tracks results over the past four decades, beginning with the 1985 crop year, when options on agricultural futures began trading again after a ban dating back to 1936. The study assumes corn and soybeans are stored from the first week of October until the expiration of July options in late June, roughly matching the term of a nine-month nonrecourse CCC loan.

Nearby futures charts show why all corn strategies wound up in the red. Corn peaked in early October, then spent the next seven months in a trading range before prices broke in May. A June rally helped futures recover some of their losses but fell short of harvest levels.

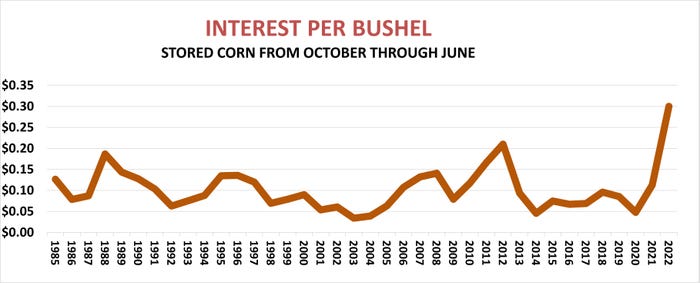

That caused flat price losses on average at the eight locations used in the study. And it didn’t help that the cost of storage overall increased. The study looks only at operating costs because depreciation on facilities varies widely depending on when they were built. And while charges for commissions and handling are fixed, a less obvious cost is variable – the value of money. The study assumes a deduction for interest on debt that isn’t paid off with harvest grain sales. And even a debt-free operation could invest harvest sales to earn interest.

For years, these interest charges were negligible. But that changed in 2022, when the Federal Reserve began raising interest rates to combat the highest inflation in 40 years. Average rates on operating loans to farmers topped 9% this summer, while the CCC charged 6.375% on commodity loans in August, with the central bank facing another decision on monetary policy at the end of its upcoming two-day meeting Sept. 20.

Last fall interest rates were only slightly lower: 5.125% at the CCC and 7.5% from ag banks. Still, the combination of higher rates and higher cash prices sent the average interest cost on an eight-month corn loan above 30 cents, easily a record since the study period began.

Cash prices should be greatly lower this fall – USDA forecasts a $4.80 average cash price for the corn crop. But with interest rates higher, these charges could still add 25 cents a bushel to the cost of storage.

That could make selling off the combine and buying call options a more attractive alternative. “Re-owning” the crop on paper this way beats the harvest price only one in every three years due to the high cost of premiums paid up front for the calls. These calls typically have no intrinsic value when purchased – they can’t be exercised for a profit. Instead their cost is strictly for time value until expiration, which is a long way off for July options at harvest. In most cases a significant rally is needed to profit from the positions to make up for time value lost over the winter and spring.

Rallies by futures or cash aren’t the only way to make money from storage of course. Some farmers do what grain elevators typically try, that is hedging inventory by selling deferred futures to capture gains in basis, the difference between cash and futures.

These so-called storage hedges for corn have the best odds historically of netting a profit over the harvest price, earning a return roughly three of every four years, though average gains are normally small. The strategy works best when carries at harvest – the study assumes between July and December contracts – is larger.

That most certainly wasn’t the case last fall, when July 2023 futures at times sold for less than the nearby December, limiting incentives for commercial hedgers.

Traders bid up the nearby because they were worried about supplies from a below average crop. Average basis was twice as strong as normal as a result, another incentive against long-term cash storage.

Both carry and basis are singing a different tune this year. Basis headed into harvest was weaker than 2022 but still stronger than average as traders await news about yields. Still, anticipated grain inventories may use around 93% of available storage this fall, towards the high end of their range over the past five years.

That helped December 3034-July 2024 carry swell out above 27 cents, improving storage hedge math for those wanting to sell deferred futures or hedge-to-arrive contracts.

Storage hedges historically rarely work for soybeans. Buyers typically want U.S. beans quickly after harvest, firming basis before the market is inundated with South American supplies during the winter and spring.

Soybeans performed a little better in Farm Futures study last year compared to corn, but only a little. The best alterative studied was selling cash off the combine and buying futures. This lowered storage costs just as most of the gains in cash soybean prices came from futures, not cash. After weakness at harvest reemerged in May, the market staged a sharp rebound through June that helped produce profits above the harvest price for those who waited.

Uncertain demand thanks to ongoing economic weakness in China and potential for a biodiesel bust cloud the outlook for 2023 soybean storage, though supplies don’t yet look burdensome. Basis headed into harvest was relatively average but November-July carries in futures was only a little less weak than corn, suggesting buying futures or options might work for growers able to find a bid off the combine.

View complete results of the study, organized by years and location:

Knorr writes from Chicago, Ill. Email him at [email protected]

The opinions of the author are not necessarily those of Farm Futures or Farm Progress.

Read more about:

Grain StorageAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like