Forecasts of U.S. corn and soybean crops continue to shrink, according to USDA’s Oct. 12 production estimates, supporting hopes for rallies into 2023. But as harvest nears the halfway point this fall, worries about demand cloud what normally should be a bullish outlook.

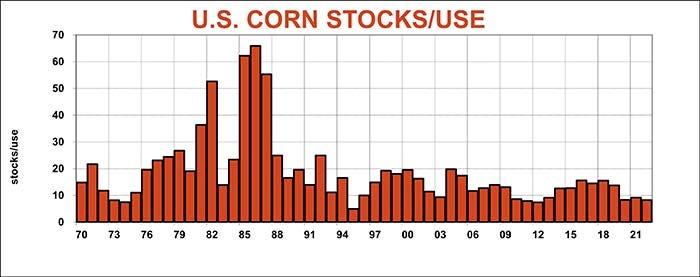

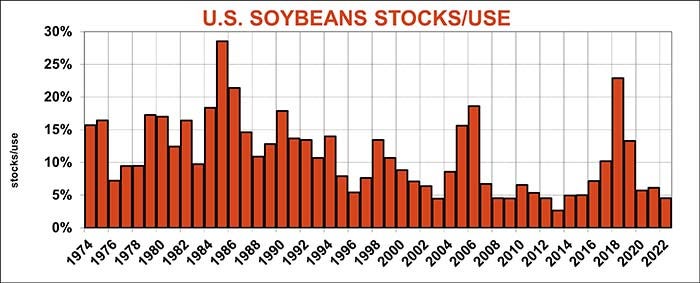

The government’s latest predictions show the stocks left over at the end of the marketing year Aug. 31 for both crops could be the tightest since recovering from the historic 2012 drought. Smaller crops and higher prices normally force end users to ration demand. This year, financial market chaos, recession fears and international risk make any forecasts even more iffy than usual.

Whether it’s the war in Ukraine or tensions with China – just to name two – impacts could be bullish or bearish, sentiment showing up clearly on price charts as the second half of October gets underway. While harsh winter weather could limit battlefront news from Moscow and Kyiv, renewed threats to world grain and fertilizer supplies from the conflict could trigger more gains. But if the war really heats up it could also topple the world economy into even deeper trouble, sucking the life out of rallies.

My price forecasting models remain optimistic about upside potential, especially for soybeans. December futures flirted with $7 last week, holding in the bottom third of my projected targets of $6.75 to $7.60. Soybeans, by contrast, are still around $1.50 below my $16.40 to $17.65 objective.

Questions about the size the crops are part of the issue. Data about corn supports USDA’s call for lower production and a national yield of 171.9 bushels per acre or less. Soybean yield indicators remain much stronger than the government, which trimmed its yield to 49.8 bpa last week.

The size of the crops won’t be settled until January, with only one more monthly estimate in November before that. In the meantime, demand and influence from crazy financial markets could continue to swing prices up or down. Here’s what I’m looking at.

Financial fallout

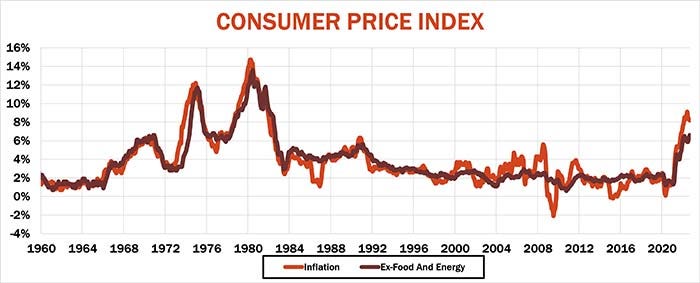

The latest bombshell rocking Wall Street came Oct. 13, when the September Consumer Price index came in at an annualized rate of 8.2%. While that continued a slight downward trend from the highpoint in June of 9.1%, it exceeded expectations. Even more troubling: When food and energy are removed, the index was 6.6%, the highest reading since 1982.

That raised worries that higher costs are being baked into the economy, creating persisting inflation

even if ag markets slump. While big speculators have been buying corn feverishly in recent weeks, that ardor could cool if grains were no longer seen as part of the bigger inflation problem.

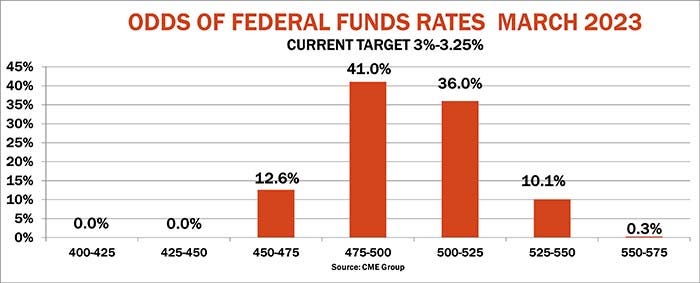

The hot CPI print sent yields on one- to three-year Treasuries towards 4.5%, as investors debated how high and how fast the Federal Reserve would raise interest rates to clamp down on prices even if it brings a recession. The central bank’s current target is 3% to 3.25% for short-term Federal Funds, and another three-quarters of 1% is all but assured at the Fed’s next meeting before the November mid-term elections. Betting by traders in Federal Funds futures increasingly sees the bank’s “terminal rate” near 5% by March 2023, suggesting more pain ahead for borrowers. Get ready for some tough loan reviews from lenders this winter.

Adding to the gloom was the latest outlook from the International Monetary Fund, which cut its forecast for world economic growth again. Complicating the mess for many countries is the strong U.S. dollar, supported by rising U.S. interest rates and demand for safe haven securities. The dollar surged to fresh 20-year highs in the wake of the turmoil.

Export drama

The strong dollar gives foreign customers less buying power to purchase corn and soybeans on world markets, where the greenback is the currency of choice. But that’s not the only worry confronting U.S. farmers hoping to sell abroad.

U.S. sales historically are a function of how our exportable supplies compare to the competition. With less to sell, the U.S. appears set to capture less of what is also expected to be a smaller corn export pie, as cash-strapped customers tighten belts and look for alternatives.

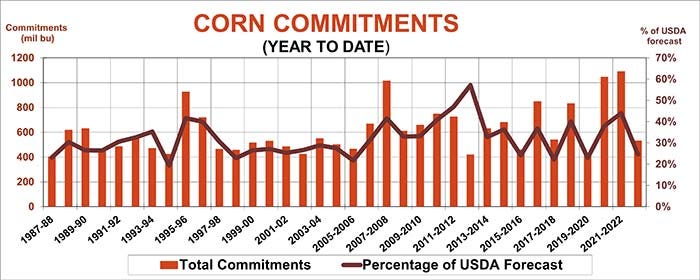

U.S. corn export commitments are already off to a dismal start, with total sales and shipments just half of the level from the last two strong years. Business could still recover. Barring an unlikely economic recovery, trouble with overseas production could force more buyers to return.

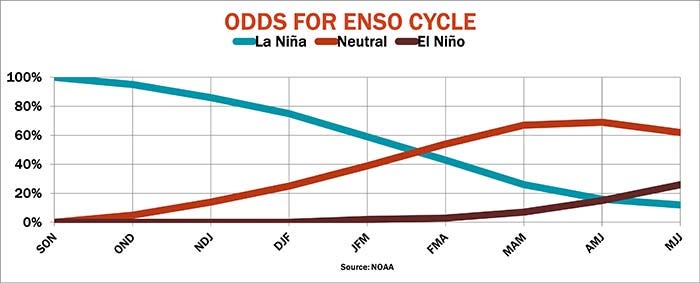

Aside from Ukraine and Russia, South America represents the biggest question mark. USDA said Brazil’s crop harvested in 2023 could be up 8.6% to a record 5 billion bushels, more than doubling the country’s exports. USDA remains optimistic about Argentine production, though local estimates there are 10% or more lower as La Nina drought again grips much of the growing area. U.S. government forecasters last week moderated their outlook for the cooling of the equatorial Pacific. They predicted La Nina conditions will last through the January-March period, instead of the February-April time frame from last month.

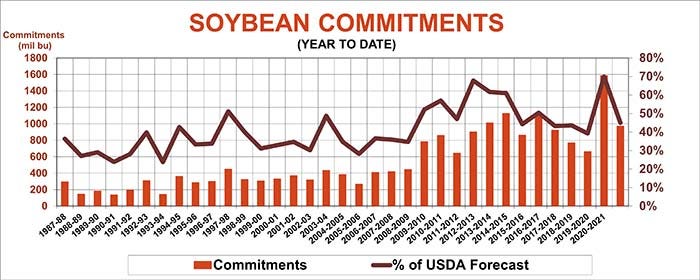

Argentine soybean production could also be hit, but Brazil again is gearing up for a record crop as planting progresses. The resulting large increase in world production are forecast to generate record global exports. But with less to sell, U.S. totals are expected to falter. The risk is that they could be even lower than the 2.045 billion bushels USDA forecasts. Soybean commitments are also down sharply from year-ago levels.

A flurry of Chinese soybean deals recently didn’t do much to turn around the export outlook. Still, China’s total imports are expected to rebound sharply from a COVID-induced slump exacerbated by government attempts to reduce soymeal feeding. U.S. commitments to China are up 12% from year-ago levels.

But China also appears ready to boost corn purchases from Brazil, dashing hopes for a U.S. resurgence. Tensions between the U.S. and China over Taiwan, computer ships and trade could be another roadblock.

Domestic dilemma

La Nina conditions normally help crops in Australia. But this year, rains are too much of a good thing, threating quality of the country’s big wheat harvest. That could put more feed wheat onto global markets, giving Asian buyers an alternative to U.S. corn.

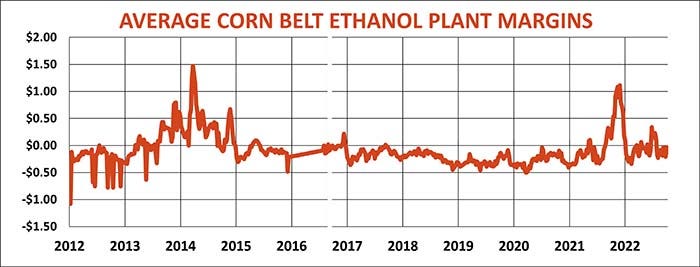

USDA said domestic corn feeding should be lower this year due to the smaller crop, but boosted its earlier forecast by 50 million bushels. The news wasn’t as good for ethanol, with the corn grind cut by 1%. The reality may be even gloomier.

The latest outlook from the U.S. Energy Department forecast ethanol production would drop more than 4%, with the amount blended into gasoline also lower than USDA’s estimate. High energy costs and shrinking wallets are curbing fuel demand, and ethanol is still too expensive compared to gasoline to encourage blending, pressuring Midwest plant operating margins.

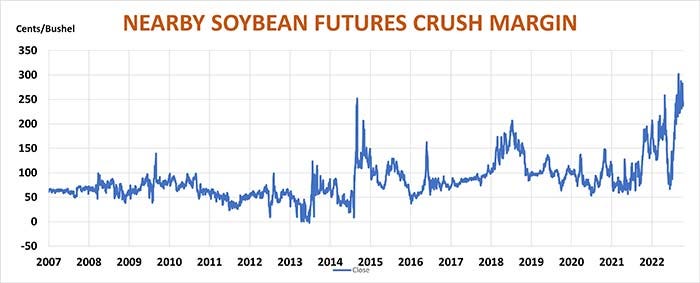

Smaller ethanol production could benefit soybeans if meal faces less competition from DDGSs. Traders expect September crush at or near all-time highs, in part due to record CBOT futures crush margins.

On an annual basis, soybean crush margins show a positive correlation to the total beans crushed from month to month. But this relationship can change during the course of the year. Strong margins can lure processors to crush too many beans, weakening profits eventually, which in turn reduces demand from plants, causing tighter supplies that in turn stimulate bids.

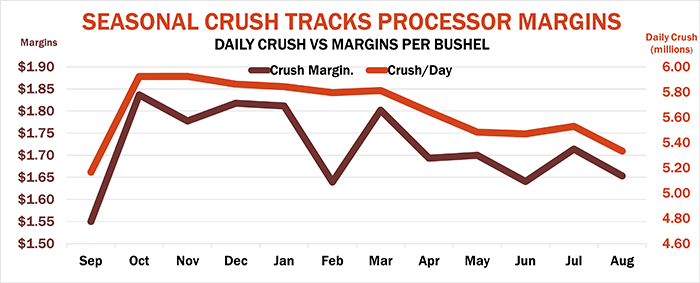

Margins also show a seasonal component. Processors on average see profits surge during October and November, when some farmers move beans off the combine. Margins tend to fade during the winter as bins are locked tight, until cash-flowing selling begins in March and sales pick up ahead of planting. After an early summer lull, black ink flows again into the end of the marketing year in August, when remaining old crop inventory is dumped ahead of the next harvest.

Soybean crush follows a similar pattern, at least in the fall, peaking in November. After that, totals used on a daily basis tail off, with the lowest usage in September before the pipeline fills again.

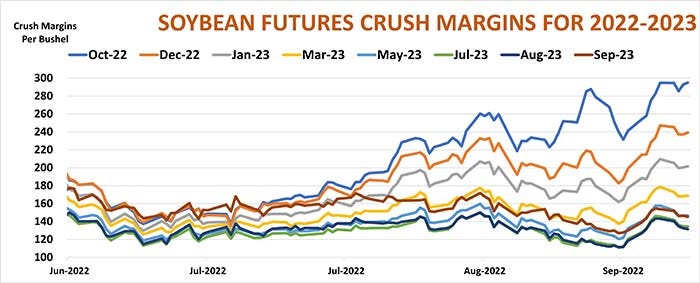

Deferred futures contracts through September 2023 show margins declining steadily but remaining above average levels for the past five years, suggesting decent prospects for processors – and growers.

Knorr writes from Chicago, Ill. Email him at [email protected]

The opinions of the author are not necessarily those of Farm Futures or Farm Progress.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like