November 30, 2023

“With tears in his eyes, he told the audience he was raised on that farm, loved farming and didn’t want to give it up,” Ron Sanert says. “Farming was his life, and now it was gone.”

The year was 1987. Clement Armstrong of Oakford, Ill., was selling his farm and his machinery. He was in his late 80s, his health was failing, and he had no children to farm the family land. He hired Sanert of Sanert Auction Service in Greenview, Ill., as the auctioneer.

“There wasn’t a dry eye in the place,” Sanert recalls. “I’ll never forget it.”

The farm was sold to Armstrong’s closest relatives, which allowed the family to maintain Centennial Farm status. It was a young couple who would raise their son and daughter on the homestead Armstrong loved so dearly.

As it turns out, the young couple were my parents. I was that daughter.

And although I didn’t know that story until recently, I share Armstrong’s affection for the homestead tucked between the walnut trees overlooking the Sangamon River bottom.

“The house that built me,” if you will. God’s country.

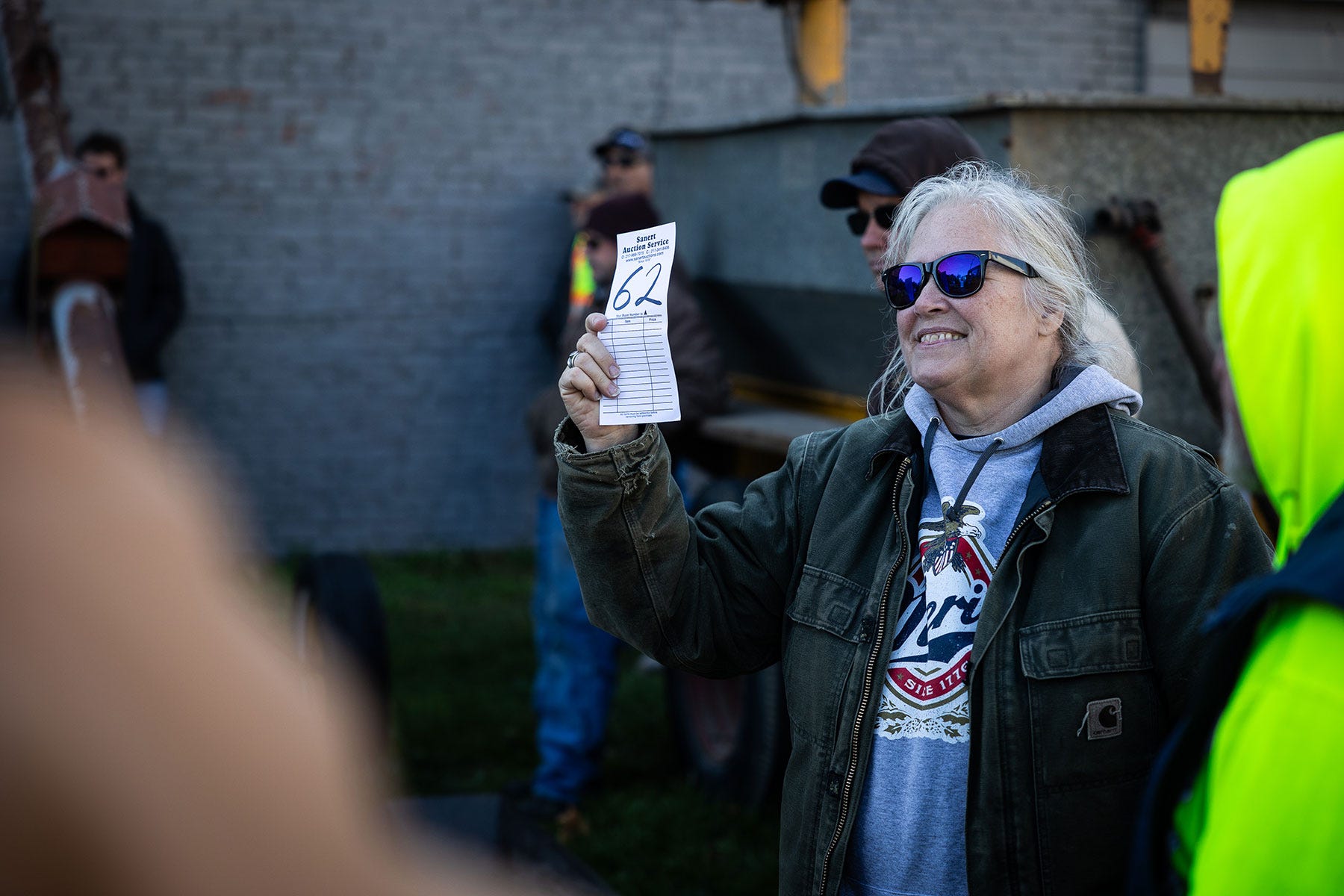

ALL SMILES: Paige Hamblin of Oakford, Ill., is all smiles with the winning bid for a New Idea disc mower. “Farm auctions are the social event of the season — a Carhartt convention,” she says.

Digital dominance

There’s something uniquely rural about farm auctions. They’re an element engrained into our culture where neighbors can gather and reconnect — whether it�’s to celebrate or to mourn.

I fear they’re also an element of rural life that’s quickly becoming extinct as auctions embrace the digital age. Live auctions may not be gone, but in my neck of the woods, they’re getting fewer and farther between. Today, there’s no geographical limit to the reach of an auction, inviting bidders from across the country. But at what cost?

“We were told about 15 years ago that online auctions were coming, and we all laughed. But they were right,” says Sanert, fondly remembering the days of his weekly auction gatherings and homemade pies from local church ladies.

RETIRING? “I’d like to go three more years to have 50 years in and say I did it. After a few more years, there might not be a live auction around,” says Ron Sanert of Sanert Auction Service in Greenview, Ill.

Gordon Watkins of Petersburg, Ill., has been an associate of Sanert’s for nearly 20 years. He says online auction platforms hurt rural communities.

“We used to bring 400 people to Greenview who would spend money at the grocery store, restaurant and tavern while they were there,” Watkins says. “One weekend, the Oakford Methodist Church made $1,000 in food sales — that’s big money for our little church. It’s something we’ve lost that we’ll never get back.”

SECRETARY: Fran Hamann of Petersburg, Ill., has been the secretary at Sanert Auction Service for almost 20 years. “Auctions used to be a place to catch up and socialize,” she says.

I was at a farm auction a few weeks ago that our neighbor called the “social event of the season — a Carhartt convention.” She was joking, but she wasn’t wrong.

There’s a sense of community lost with the digital age. And like volunteer organizations and small-town grocers and rural veterinarians, the loss of live farm auctions seems to be the next nail in the rural coffin, from an increasingly “connected” digital world that lacks true connection.

The kind of connection where you stand alongside your neighbor and fight back tears as they watch their livelihood sell to the highest bidder. The kind of connection from knowing your legacy will carry on as you pass the torch to a family who will love the land as you once did.

BURGER: My daughter, Clare, eats a cheeseburger at Sanert Auction Service in Greenview.

What’s happening with live auctions in your community? Email [email protected].

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like