Whether it’s spring or winter wheat, The Mill at Janie’s Farm in Iroquois County is milling organic wheat harvested in Illinois year-round. Just like other organic processors across the country, its sales are increasing rapidly, and it’s grinding to meet demand.

At the facility, corn has already been tested on a new two-mill system from Denmark. After January, owner and farmer Harold Wilken says they’ll be milling batches of organic corn into varying consistencies, ranging from fine meal to coarse grits.

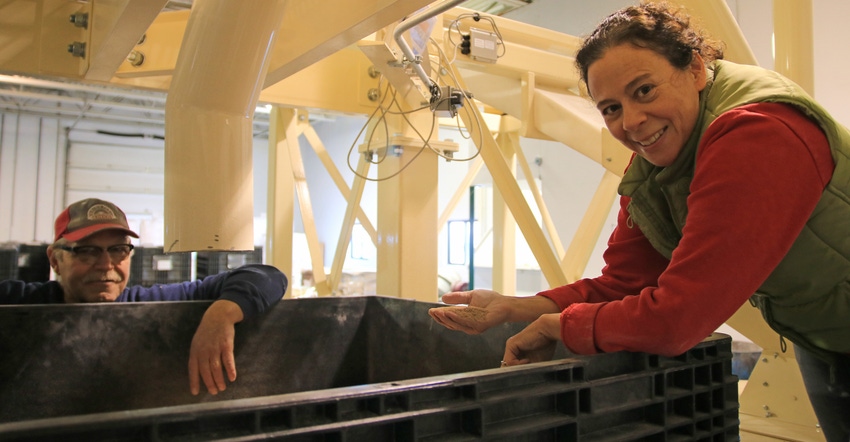

“I think the time is right for the mill and for these stone-ground flours, because people are increasingly concerned about what goes into their bodies,” says mill manager Jill Cummings, referring to the commercial process of grinding grain, extracting parts of it, and fortifying what remains with nutrients.

She says The Mill differentiates its flour from whole-wheat bought at stores by calling many of its products whole-kernel.

“Ours is 100% whole-kernel: You have the bran, you have the endosperm and you have the germ, whereas what they call whole-wheat at the store is run through a roller mill that extracts everything except for the endosperm, the white part of the kernel,” Cummings says, adding that bran, fortifiers and vitamins are added back in to earn the whole-wheat label.

“Enriched sounds really good, and you are getting vitamins, but ours is the real deal. What is in the grain is what you get in the flour,” she says.

Since the oil content of the germ is spread throughout the product, whole-kernel flour doesn’t have a long shelf life. The Mill also sells extracted flour, including all-purpose flours, sifted bread flours and pastry flours — products where they’re removing some of the bran.

Wilken is able to meet much of the wheat demand of his mill himself, though he also buys wheat from five other farmers to spread risk.

Cummings says Wilken keeps himself busy with farming, finding new customers and maintaining relationships, mainly in Chicago and St. Louis. But he also makes trips to Ann Arbor, Mich., and Kansas.

“I was told we could not raise spring wheat here. But we've got really good quality, and I'm actually delivering grain out to Kansas City,” Wilken says. “We’ve got a baker that buys Glenn wheat from us, which is a high-protein spring wheat. They’re on the edge of the wheat belt, and they’re getting their wheat from Illinois.”

‘Cold turkey’ on conventional since ’05

Wilken has farmed organically near Ashkum, Ill., since he and his son, Ross, started transitioning a 30-acre piece of conventional land in 2003. Wilken quit conventional farming “cold turkey” in 2005, and now farms 2,800 acres that are either organic or are transitioning to organic.

“I get calls sometimes from landowners looking for someone to transition their land to organic. If it’s close, we’ll do it; otherwise, I put them in touch with some farmers I know that are just starting out,” Wilken says.

Following a transition period of soybeans, wheat and cover crops, Wilken raises five crops across four-year cycles — two of which he plows under when he tills, or “composts” the top layer of soil and manure application remnants. The rich soil coagulates and clumps after rains, and he sees soil health improve every year.

“It takes a while for animal manures to break down, so then after about five years, you’ve had three or four different chicken manure applications,” Ross says. “The soil becomes noticeably healthier.”

He adds that while he’s not opposed to no-till organics, he’d want to approach it the same way he approached organics when he started as a 15-year-old.

“Organic farming is very different,” Ross concludes. “You want to try things on a small scale.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like