Using battlefield tactics on the farm to aid growers in precision decisions

“Just as we do with precision weapons, we can go out and precisely target where the pigweed problem is, and with GPS-enabled variable rate equipment, we can put together a program script and apply just the right amount of the right stuff at the right place at the right time.”

May 4, 2018

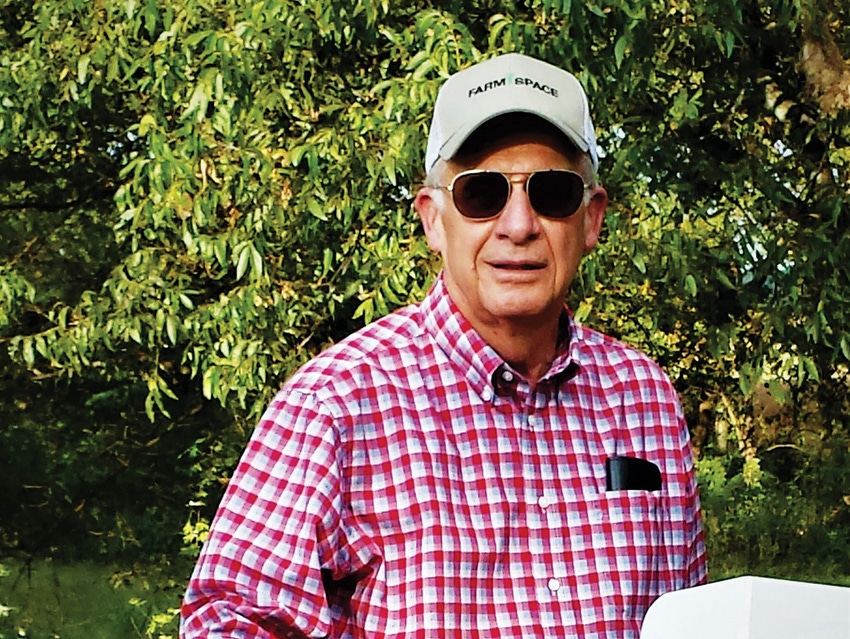

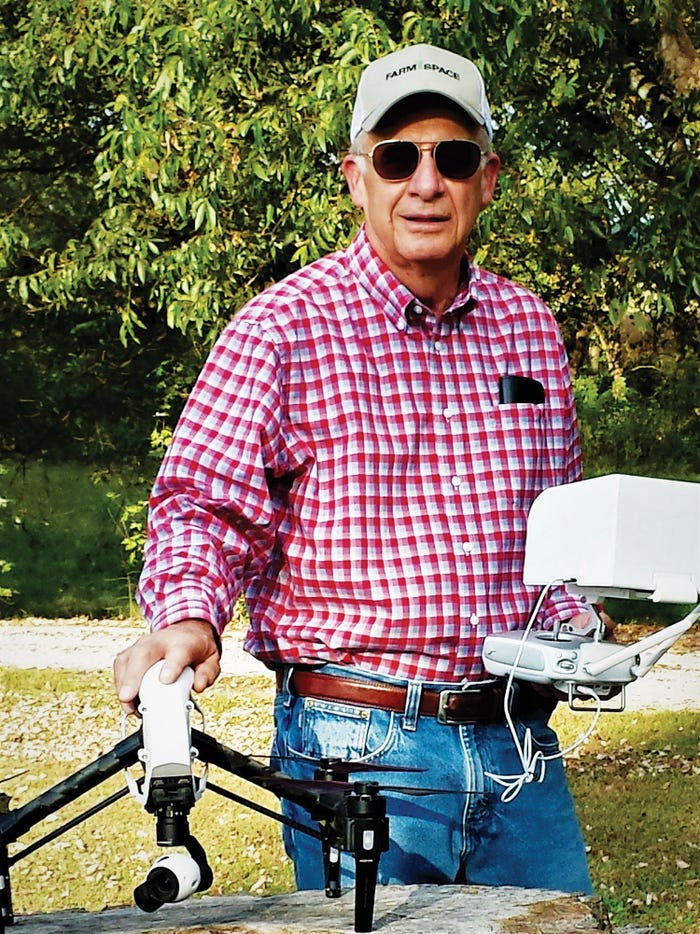

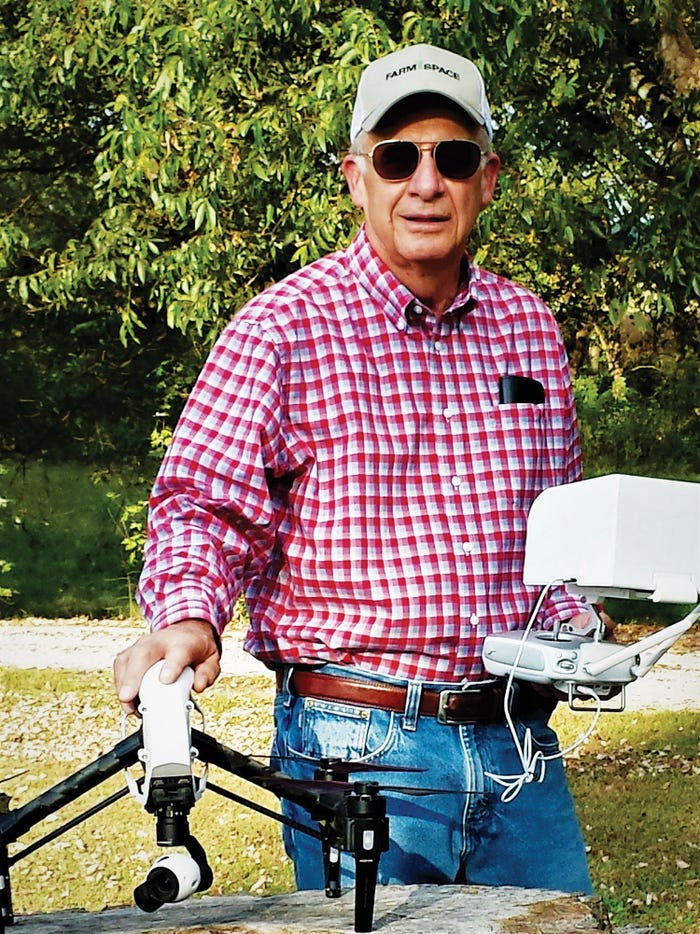

Incorporating tactics he used during his 36 years of service in the U.S. Marines, retired Lt. Gen. John Castellaw joined forces with retired Air Force Capt. Derick Seaton to form Farmspace Systems LLC, an operation in which the ex-military duo are implementing battle-space strategies, but in the farm space.

The U.S. military has been credited with major technological advances that have been adopted by precision agriculture, from the introduction of airplanes to the use of GPS systems — originally created for greater accuracy in lobbing thermonuclear warheads — to the use of unmanned aerial vehicles, UAVs/drones.

“When you’re a commander and you’re assigned a battle space, what you want to know is everything that’s going on in that battle space, and what you can do to impact it in order to reach your objectives,” says Castellaw, who is CEO of the Alamo, Tenn., company. “And you want to know that information as soon as you can get it.”

A helicopter pilot in the military and a certified remote pilot-in-command, he says, “We would get information from satellites, as well as aircraft and people on the ground providing reports. We had an aggregating platform that allowed us to bring all this information in, collect it, process it, analyze it, and then come up with an actionable piece of information that gave us the overall situational awareness and plan of action.”

Data and images collected by UAVs are enabling a similar approach to precision agriculture, Castellaw says. For example, if a grower has identified a pigweed problem in a particular area using drone technology, he or she can use those data, along with statistical information collected by farm-specific software, such as soil types, moisture content, and harvest history, to generate an actionable plan.

CAN PRECISELY TARGET PROBLEM

“Just as we do with precision weapons, we can go out and precisely target where the pigweed problem is, and with GPS-enabled variable rate equipment, we can put together a program script and apply just the right amount of the right stuff at the right place at the right time,” he says. “It can take the data already collected, field history, etc., form a snapshot of what’s happening now, and then act on that information. It’s about having additional information at your fingertips so you can make a professional judgement and perform an action.”

Lori Duncan, Tennessee Extension specialist in biosystems engineering, holds a custom quadcopter UAV with a multi-spectral camera.

In corn fields, Farmspace uses artificial intelligence to conduct stand counts. “What we can do is identify each plant in the field, compare the plants that are up and growing with the seed you planted, and determine if you’ve got enough germination or emergence.”

With this information, growers can then determine whether or not they need to replant in specific areas. “We are able to do that using artificial intelligence — deep learning,” Castellaw says. “We modify programs for them to look for a corn plant or a cotton plant or weeds, then run the image that’s been stitched together through the software to identify and count the plants.”

The market for drones in smart agriculture is predicted to increase from approximately $670 million in 2015 to $2.9 billion by 2021, according to a report on statistica.com. And while aerial imaging is not new in agriculture, the use of drones is allowing growers a closer look — even on an individual plant basis — and doing it more quickly.

CHALLENGE: INTERPRETING DATA

“A drone is basically just a new platform, with obvious advantages, for collecting the same sort of data that we’ve been getting for decades from airplanes and satellites,” says Lori Duncan, University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture Extension specialist in biosystems engineering. “It allows us to have much higher spatial resolution, and we can fly more often — which changes the game. The challenge lies in interpreting the data into a meaningful agronomic decision.”

Historically, satellite images have been used to give growers a birdseye view of their crops, providing a resolution of 30 meters. UAVs allow growers to zoom in even closer. “With these drones, there’s not a limit on our spatial resolution, so when we fly I can get down to an inch in resolution,” says Duncan, who uses drones to conduct applied research.

“There’s a lot of data, but because we’re now into the era of precision agriculture, it’s hard to make precise recommendations on a 30-meter pixel basis. And if we’re talking about making any site-specific applications — be it fertilizer, pesticide, or whatever — it’s really hard to make any kind of educated guess on a 30-meter image. But, if we’re down at the sub-inch level, we can readily see if it’s a weed or if it’s a cotton plant.”

Irrigation management is another area employing drone technology, Ducan notes. “They can fly a field with a thermal sensor and see hot areas, or where the plant has stopped transpiring and is getting hotter and needs to be irrigated.”

For 56-year farming veteran Jimmy Hargett, who grows cotton, corn, soybeans, and wheat in the rolling hills at Bells, Tenn., drones have taken the footwork out of managing his multiple irrigation sprinklers, providing him a live view of his pivots so he can quickly determine if there’s a flat tire or some other issue.

REMOTE MONITORING OF PIVOTS

“I have 29 irrigation systems, and it is a major job looking after them,” says Hargett, a 2010 Delta Farm Press High Cotton award winner. “I’ve been working with Farmspace for four or five years. With the last drone they brought, I can sit in my shop, tell it to take off, tell it which pivot to go to, and it will go to that pivot. It will fly down the length of the pivot, turn around, then fly back down the sprinkler and return to the shop.

Retired Lt. Gen. John Castellaw implements battle space strategies on the farm with UAVs.

Retired Lt. Gen. John Castellaw implements battle space strategies on the farm with UAVs.

“I can take the information off of the drone, or I can look at the photos when it’s done. The main thing I wanted to be able to do was to see my irrigation systems, if they’re working, because it’s a heck of a job to drive to all those pivots.”

On rice farms, Castellaw says, drone technology allows growers to check water levels while they are flood-irrigating their fields, saving time and resources. “Instead of driving all the way around a field, they’re using drones to determine when the water gets to the other side.” Drones can also be used to determine low places in a field, elevation models, detect nutrient deficiencies, and identify weeds.

A promise made, but broken, brought Castellaw back to his more-than 100-year-old family farm. “The first promise I failed to keep was to my wife when I graduated from the University of Tennessee. I said, ‘Honey, in three years we’re back on the farm.’”

But he stayed in the military for 36 years, during which the couple moved 25 times around the world, finally making it back to their Crockett County, Tenn., farm, where as a teenager driving a new 4020 tractor, Castellaw would apply 500 pounds of 6-12-12 over his entire farm.

TAILOR-MADE APPLICATIONS

“What you can do now, instead of applying 500 pounds of 6-12-12 over the entire farm, is to get your fertilizer mix to match what’s in a particular zone (2.5 acres to 5 acres) and put down maybe 300 pounds of some other mixture. So, with that variable rate, GPS-enabled piece of equipment, you apply only what that particular zone needs — not too much, not too little, just the right amount.”

A grower can also do the same thing with seeds and variable-rate planters in areas that can support a larger seed population, Castellaw says. “Again, it reduces the amount of inputs required to farm, which means less cost of production, greater yields, and at the same time we’re being better stewards of the land because we aren’t contributing to problems such as nitrogen leaching and run-off. We make the environment better for all of us.”

You May Also Like