February 10, 2021

In my last column, I covered the first part of utilizing BMR forage sorghum — the male sterile version — to produce high-quality forage for dairy production.

The sorghum is cheaper to grow per acre than most corn varieties. If it’s grown the year before corn, it will eliminate corn rootworm for the first year or two afterward. Deer even hide in it and then come out to eat the neighboring corn.

The problem is that most sorghum has a grain head that, as it fills, lodges the crop, making it difficult to harvest. The use of a male sterile variety eliminates the weighty head on a thin stalk. Instead of increasing digestible components by filling a seed head — vitreous, hard-to digest starch — it keeps those components in the forage cells. This increases the milk-producing ability while simultaneously increasing the dry matter of the forage.

The question we’ve had all along is: How long should you let the crop grow after heading before ensiling?

In our study, we went seven weeks post heading. As reported in my previous column, the sugar component as measured by wet chemistry increased 500% to 18.85% of the dry matter. This was measured after fermentation (three weeks), so it reflects what the cows would be consuming from the ration.

Components shot up, except starch

There are more components that increased. The non-fiber carbohydrates increased 71% to within 82% of what normal corn silage produces. The nonstructural carbohydrates increased 185%. The neutral detergent fiber went down 15%, which is the reverse of most crops as they mature. The reason is the fiber was being diluted by highly digestible components.

The digestibility of the NDF, which normally goes down with maturity, only dropped 8% over the seven weeks and was 64.1 NDFd30-NDF.

The starch increased nine-fold, but it was only one-tenth of what’s normally in high-grain corn silage. The energy was held in the very high sugar in the cells rather than converted to starch (starch is 2,000 to 200,000 sugar molecules). So, the energy was there but in a different form. The BMR sorghum forage was 30% higher in crude protein — 10.28% crude protein — than the corn silage.

But it’s not corn silage

The most critical factor in feeding high-quality BMR sorghum is that BMR sorghum silage is not corn silage. This needs to be stamped on the forehead of your nutritionist.

We had a 30,000-pound herd in the Midwest that put BMR sorghum in the diet, and they maintained production. We also had one farm in New York that had the same herd average until it swapped corn silage for sorghum silage, and the cows lost production. This clearly shows that BMR sorghum silage is not corn silage.

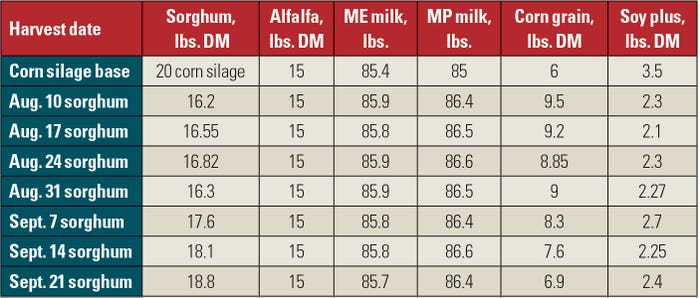

In the initial ration that Larry Chase, professor emeritus of animal sciences at Cornell, put together, we did the simple swap. It showed the 85 pounds of milk supported by corn silage dropped to 79.4 mature equivalent with the sorghum silage.

Sorghum is slightly lower in energy than well-eared corn silage, but it is higher in crude protein. These rations contained 60% of the forage dry matter as sorghum silage and 40% as alfalfa silage.

By rebalancing the ration, the ME was the same as normal corn silage, and the protein was considerably higher than the corn silage. The key is to increase the NDF feeding levels to 1% of bodyweight as it has higher digestibility than the corn silage. As the NDF levels decreased in the later harvest dates, we were able to feed 2.6 more pounds of BMR sorghum dry matter to the cows.

If you look at the right side of the table below, you can see that the earlier harvested sorghum required 3.5 more pounds of corn meal — 9.5 pounds — than the corn silage — 6 pounds — to maintain milk production.

It did it, though, with 1.2 less pounds of SoyPlus per cow per day. By allowing the crop to increase quality components with increased time after heading, the energy accumulating in the plant increased until only 0.9 pounds of extra corn meal — 27% reduction over early head harvest — was needed to match the corn silage milk production and 1.1 less pounds of SoyPlus compared to the corn silage.

Plugging in the grain cost of last week (they are changing rapidly) using sorghum on a 100-cow dairy with a 305-day lactation resulted in $3,294 more in corn grain costs, but $8,388 less in SoyPlus costs. If soy prices fall back to more normal, the two crops on a feeding or economic basis will be nearly equal.

Kilcer is a certified crop adviser in Kinderhook, N.Y.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like