I like to think of grain marketing as a game played with two halves. The first half is pre-harvest marketing, or pricing actions taken before you harvest the crop. The second half occurs after harvest and involves a question, “To store, or not to store?”

2013 has been one tough year for marketers. In hindsight, there were many good pre-harvest pricing opportunities in corn and soybeans. But the previous two years punished producers who priced early, and this year too many producers stayed on the bench for the entire first half. With no points on the board, there is a lot riding on a great second-half performance. The strategy is simple: Store low-priced grain at harvest and wait for seasonally higher prices next spring. How much confidence should we have in waiting for higher prices next spring?

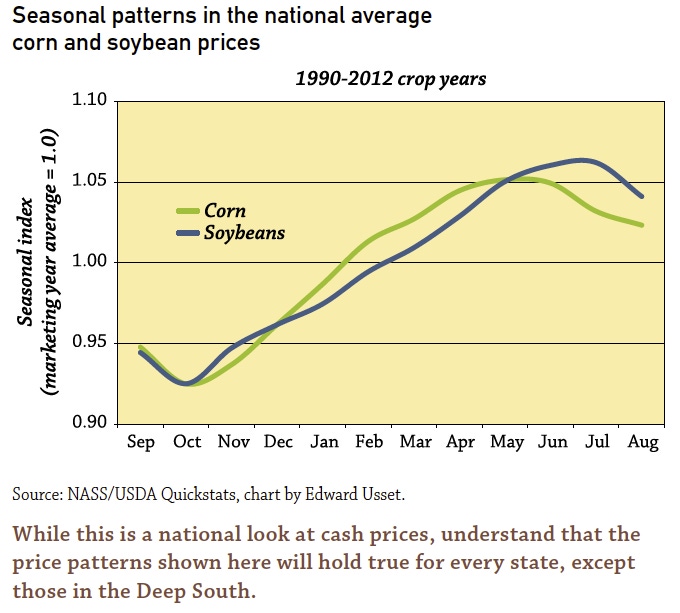

Let’s explore this question with an analysis of national average corn and soybean prices received by farmers. On average, there is a strong seasonal tendency for cash prices to rise from harvest lows to highs in late spring (corn) or early summer (soybeans). This seasonal pattern has been remarkably stable over the decades. If I showed you the seasonal pattern for the 1960s, 1970s, or 1980s, you would be amazed at how similar they look to the 1990-2012 period. This surprises some people because so much has changed in the past 50 years – policy changed, ethanol changed the corn market, and Brazil production and Chinese imports changed the soybean market. But all this change overlooks a simple fact - seasonal price changes are rooted in the grain production cycle, which has not changed.

These enduring seasonal patterns give us reason to feel good about unpriced grain in storage, including…

1. Corn and soybean prices in June are higher than the previous October price in 4 out of 5 years; 80% is pretty good odds.

2. Since 1990, the average price rise from October to June is 13% in corn and 15% in soybeans. Based on $4 corn and $12 soybeans, that translates to a 50-cent per bushel rise in corn and $1.80-bushel rise in soybean prices. Prices rose more than average in one-third of the years in corn, and nearly half in soybeans.

In case you get too comfortable with grain in storage, here are two sobering thoughts:

1. Seasonal patterns speak to the “average” year, but every decade has one or two atypical years when prices go against the seasonal. Check out prices in fall 2009 – by spring 2010, corn and soybean prices were lower.

2. I’m concerned about the basis, particularly in corn. You may be surprised to learn that the primary driver behind seasonal price changes is a rising basis from fall to spring, and not futures prices. Larger corn stocks point to a weaker basis next spring.

Here’s to a strong second-half of the marketing game.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like