October 23, 2023

Indiana has some of the best agricultural land in the world — and it is losing substantial chunks of that best ground to urban sprawl. But according to Cris Coffin, director and senior policy advisor for the National Agricultural Land Network, there are ways to both support economic development and preserve ag land at the same time.

“We’re not anti-development,” Coffin says. “Rather, we’re about encouraging communities to become smarter in how they allow development, particularly residential development, to limit the conversion of agricultural land we would consider to be unnecessary.”

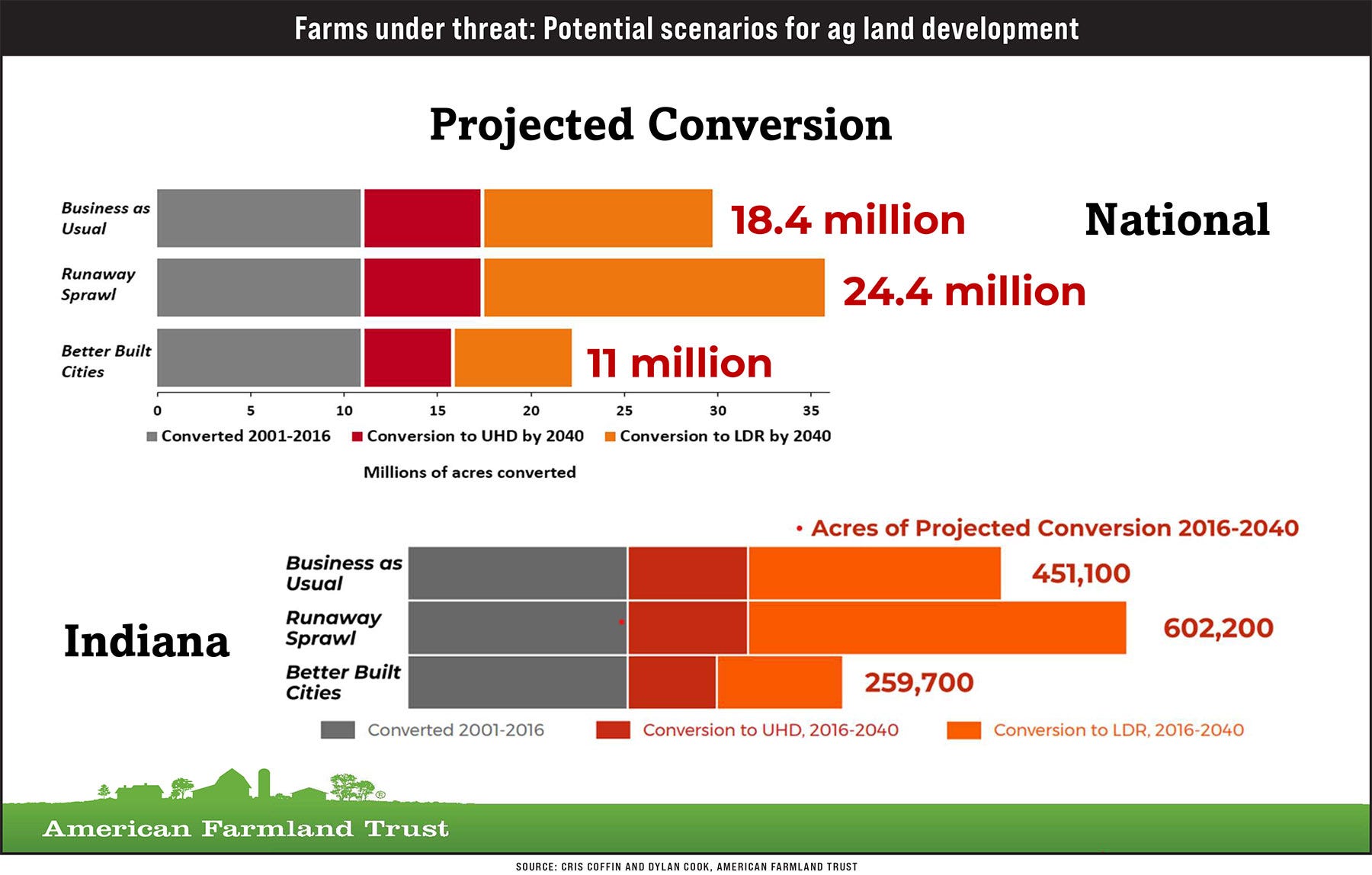

Coffin described NALN’s Farms Under Threat multiple-year initiative, which seeks to document the status of and threats to U.S. agricultural land while offering policy solutions to save that land. There are two primary types of development, she notes: traditional “urban and highly developed” land and “low-density residential,” which includes less dense subdivisions in rural areas where residential use is intensifying.

Where farmland goes

Two primary culprits in unnecessary prime farmland loss include low-density residential development and solar farms. Solar farms have exploded in the past few years, due in part to the Inflation Reduction Act.

Coffin cites a study stating that from 2001 to 2016, Indiana lost 265,500 acres of cropland, pasture and woodland to development. About 39% was lost to urban and highly developed uses, while 61% went to low-density residential. And low-density residential is like soil erosion, in that once it gets started, it gets worse rapidly.

“Our study showed that ag land in low-density residential areas in 2001 was 22 times more likely to be converted to urban and highly developed by 2016,” she says. “This matters, because development on good agricultural land makes farming what’s left considerably more difficult, and ultimately drives farmers away to more marginal land, with slimmer profit margins.

“It also drives up the price of land for beginning farmers, whom we desperately need to replace our rapidly aging farmer population.”

A smarter way

A major thrust of NALN’s Farms Under Threat initiative is looking ahead to 2040, envisioning different scenarios of what could be the future of farmland in Indiana. To do so, Coffin offers three examples:

1. Business as Usual. This is the historical rate, in which development continues at its current pace.

2. Runaway Sprawl. If left unchecked, loss of good agricultural land will disappear at an increasing rate. Land conversion to urban and highly developed would be the same as under Business as Usual, while low-density residential projects would be 50% higher.

3. Better Built Cities. In this scenario, land conversion to urban and highly developed would be 25% lower than Business as Usual, and conversion to low-density residential would be 50% lower.

“The pandemic slowed conversion of agricultural land to low-density residential development, so we think that in some places, the trajectory will more likely track our projections toward Runaway Sprawl than these figures show,” Coffin says. “But if we can move toward the Better Built Cities model, in which development is more compact, then we can hopefully become smarter in how we allow development, particularly as it pertains to low-density residential development.”

These figures do not include solar construction. In addition, Coffin says the initiative’s projections for 2040 show increasing stress to prime farmland throughout the Midwest caused by climate change. In Indiana, areas that will be most impacted include counties in roughly the northern fourth of the state, along with other areas in southeast and southwest Indiana. The effects of climate change will further exacerbate the loss of agricultural production from good farmland caused by indiscriminate development.

Where Indiana ranks

In terms of taking steps at the state level to protect farmland from unnecessary conversion, Coffin suggests Indiana was late to the party and needs to pick up the pace in protecting its best farmland. Indiana is in the highly unenviable position of being under a high threat to agricultural land while also having a low policy response.

By comparison, other lower-population-density states like Iowa, North Dakota and South Dakota also have low policy responses, but they are not facing the high development threat that Indiana is, with a much higher population density. More urbanized states on the East Coast and California have a high threat to ag land but have taken more steps to protect it.

“Indiana needs to plan for agriculture by recognizing agriculture as the ‘factory floor’ for an essential state industry, encouraging planning that supports agriculture and economic development and stabilizes the land base, providing information about the fiscal and economic impacts of development choices, and providing planning tools for solar development,” Coffin says.

For solar development, Coffin suggests “smart solar principles” that would:

prioritize non-ag land

avoid the best farmland

require soil health practices during construction, operation and decommissioning

maximize use of agrivoltaics, which combines agriculture and solar

encourage farmers to use solar power for their operations as appropriate

expand engagement among diverse stakeholders

Better state policies needed

Coffin also encourages state leaders to review state development incentives to avoid incentivizing development on productive ag land. Indiana could also consider adopting voluntary “agricultural districts” that provide additional protections and incentives to enrollees. Neighboring states that have created agricultural districts include Ohio, Illinois, Iowa, Kentucky and Wisconsin.

Other states use conservation easements, which provide some opportunity for permanent farmland protection. Michigan and Pennsylvania created such protections, although they have differing approaches.

“There is no one single policy approach that in itself is a magic bullet,” Coffin says. “What is really needed is multiple and coordinated policy approaches, including planning, financial incentives and permanent protection options, all of which need to be based on solid data.”

To learn more, visit farmlandinfo.org.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like