Iowa farmer Robb Ewoldt recalls the day a landowner asked him to rent his farm. When Ewoldt heard the princely sum the owner had been getting, he stopped the conversation.

“If that’s the case you ought to keep renting to your current tenant because I’m not going to be on the hook for that kind of money,” he recalls telling the owner. When asked why the rent was so high, the owner’s response sounded familiar: he had missed out on high cash rents when profits were soaring back in 2013, and now wanted to make up for his losses.

“I told him, I’m not going to make up for your mistake because today’s grain prices don’t demand that kind of rent,” Ewoldt says. “But what I can do, to make sure you don’t miss that opportunity again, is set up a flex lease with a guaranteed base rent, and as price or yield goes up, split the additional profit 50-50.

“They were willing to take a lower flat rate with potential upside.”

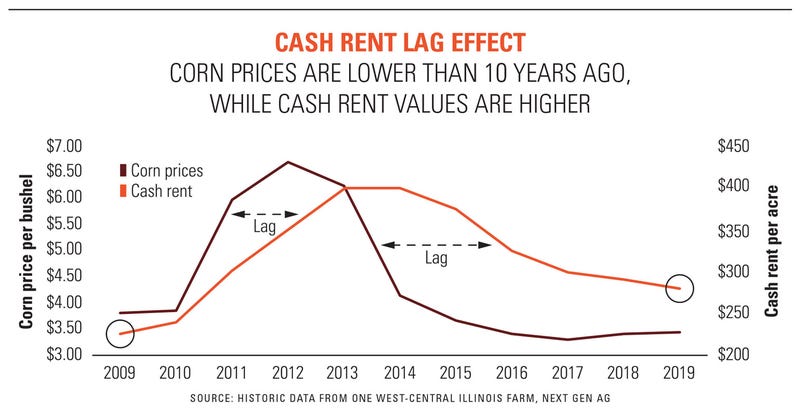

Ewoldt’s story is more common than you think says land lease consultant Mike Downey, Lisbon, Iowa. Because cash rent leases are usually year-to-year with terms based on past performance, both owners and operators grapple with “what’s fair.” When grain prices rocketed higher from 2010 to 2013, tenant farmers made money as cash rents were slow to respond; then, as prices deflated over the past six years, cash rents were slow to respond and landowners made money (see chart).

Land rents are slow to rise when farm profitability jumps, but sticky to fall when profitability evaporates if there’s competition in your neighborhood (and there always is).

A flex lease removes anxiety for both parties and takes the heartburn out of the annual lease discussion.

“These agreements move with what’s happening now instead of basing cash rents on what happened last year,” notes Downey.

But it can only work if both parties trust each other.

“There has to be a lot of trust between owner and operator, to know the operator is telling the truth on expenses and be willing to share your numbers,” says Ewoldt, who grows 900 acres of corn, soybeans and alfalfa near Davenport. “When you’re open and not keeping any secrets, it builds a better relationship between landowner and operator.”

Ewoldt’s flex lease is set up with a base guaranteed rent per acre with an additional $100 per acre potential returns to management (Ewoldt); then, revenue on top of that is split 50-50 between owner and operator. Ewoldt says in recent years he’s been able to hit that $100/acre profit goal mainly through better production, not prices.

“I love it when we beat that $100/a level and write that bonus check to the owner,” Ewoldt says. “It feels like it’s a team effort – we’re both in it together instead of the adversarial role that you usually see.”

Less heartburn

Most people say their number one fear is public speaking. For some farmers it’s having to discuss next year’s lease with landowners.

Corn belt agriculture has a lot of sound business practices but going through annual land negotiations is not one of them. Operators face land base insecurity; unfortunately, a similar anxiety exists for many landowners. Some are not sure how much to charge and many believe they are being taken advantage of, for real or imagined reasons.

“This annual tension creates winners and losers, and it does nothing good for the landlord-tenant relationship,” says Downey, a former farm manager who consults with both owners and tenants at Next Gen Ag Advocates, based in Iowa.

In 1982 crop share leases made up half of all farmland leases; by 2017 they made up less than 20% as cash rent became the gold standard. While it’s simple for both parties to understand, the one-year cash rent lease puts all risk on the operator, creates tension between the two parties, and discourages investment in multi-year conservation projects.

“When there’s a winner and loser that doesn’t facilitate a long term relationship,” says Steve Bohr, farmer and Next Gen co-owner. “At best it creates a stressful relationship. There has to be give and take but in the land market there is often no give and take. Unfortunately as farmers we don’t have a lot of alternatives.”

A flex lease may be a better solution for both parties.

The base rent is fixed, and operator and owner share upside rewards from higher yields and prices. And flexible leases continue to make gains across the Corn Belt.

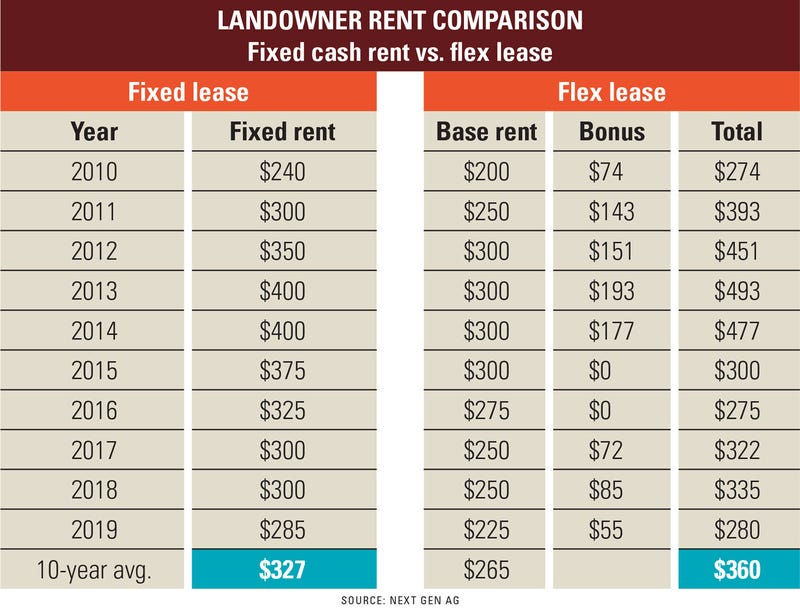

Landowners may be wary of accepting a lower base rent in exchange for potential higher rent after revenue is calculated. But flex leases with a base rent plus bonus historically provide more landowner returns than cash rent (see table).

How it works

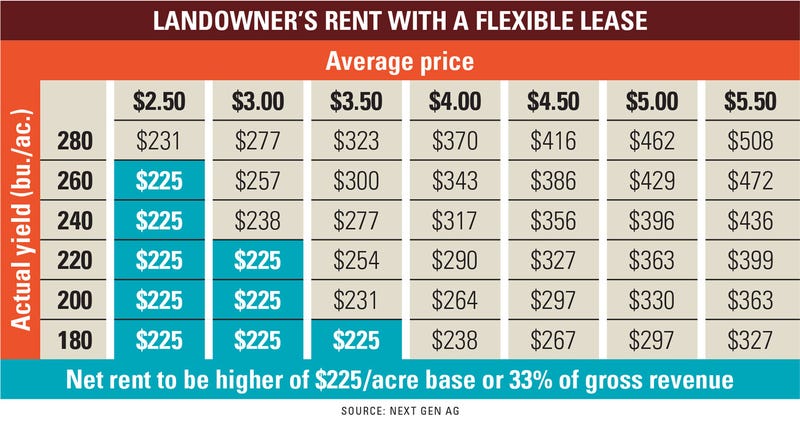

Downey uses 33% of gross revenue to set up base rents on corn acres. That figure comes from averaging Iowa cash rent as a percent of gross revenue over the past 12 years.

So, let’s say you have a good year and corn yielded 220 bu. per acre. You also made some good marketing moves and sold at an average $3.50 per acre. Based on the sample table, landowner returns rise from $225 to $254/a.

Your rent table should be adjusted to local cost parameters but most important, it should be seen as fair by both parties.

With a flex lease operators won’t hit as many ‘home runs’ when yields and prices soar, but it also means they cut risk of drastic losses if production and prices collapse.

Go beyond price alone

“What we found is, once we set these up it really facilitates a better relationship,” says Downey. “There’s a lot less pressure on that annual rent discussion because to some extent the lease terms are already established.”

Flex leases push the discussion beyond the rent price to focus on what producers and landowners actually need and want in a lease.

Besides income landowners want someone to take care of fertility, stewardship, and conservation practices, for starters. They may want other things like mowing, soil health measures, or organic production.

But what do producers want, other than a lease that offers a chance at net profit?

“By far producers tell us they are seeking long term relationships,” says Downey. “That’s hard to build with a one-year agreement.”

Soil health and climate-smart farming practices call for long-term management practices, and that can be accomplished in a multi-year flex lease.

Ewoldt says it’s been a win-win business practice that he hopes will grow with future new leases.

“Those flex leases are some of the best relationships I have with landowners,” he concludes.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like