If you want to make an easy joke in Illinois, you’ve got two quick targets: First, bring up the imprisoned governors. Then, mention the ridiculous taxes — especially property taxes, if you’re in a farm crowd.

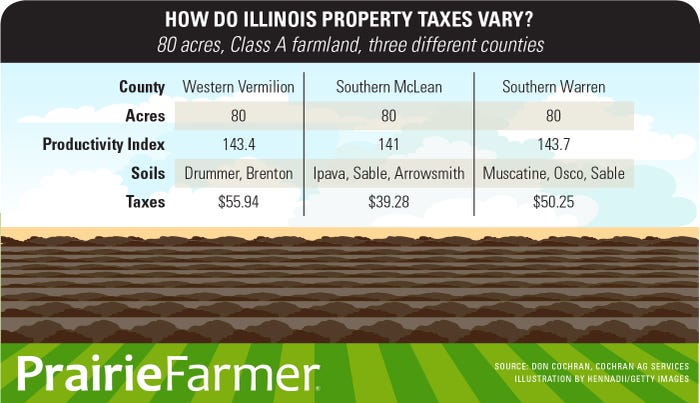

Jokes aside, Illinois farmland taxes are both high and complex. How do they really work?

“The idea is that we assess farmland based on its potential to produce an income,” says Brenda Matherly, director of local government for Illinois Farm Bureau. “Higher-quality soil has higher potential to produce income.”

That’s the simple version, of course.

All property taxes are local, meaning zero percent of property tax dollars go to the state.

“It’s easy to say, ‘Well, no wonder my taxes are going up, because the state is broke,’” Matherly says. But the state doesn’t touch property tax dollars; instead, taxes fund local services such as schools, roads, counties, emergency medical services, fire, police, libraries, recreation centers, etc.

Tax rates vary drastically, according to municipal taxing bodies. If your school district also has a nuclear power plant nearby, you won’t pay as much. If you’re in a rural school district with lots of farmland but few residential or commercial properties? “They have to meet all their financial needs on the backs of farmers,” Matherly says.

So why does it seem like it’s better across the state line — any state line? Matherly says it’s because of the way taxes are collected. For example, Indiana has a lower property tax rate, but it also collects personal property tax and local income tax, all of which are used to fund local endeavors. That means comparing taxes on an 80-acre farm in Illinois to an 80-acre farm in Indiana isn’t apples to apples; Indiana also taxes income on what you raise, and personal property tax on the crop itself (including livestock).

Illinois’ personal property tax was declared unconstitutional in 1970, so to fund local government, Illinois residents pay higher property taxes. In effect, that means farmland owners pay a larger percentage of tax to schools — somewhere around 60% of their taxes fund school districts.

Tax caps

Back in 1986, the state Legislature enacted a 10% limit on movement of farmland taxes, which says the value can’t change more than 10% each year. The idea was to safeguard taxing districts and the farmland owners from drastic annual swings. But it also limited tax assessment growth on poorer soils. In 2013, an amendment declared that soils with a productivity index of 111 could change, and all other soils would change relative to that figure. The result is supposed to bring poorer soils up in tax assessments, over a period of years.

The percentage isn’t clean-cut. Matherly explains soils can change no more than 10% of the median soil productivity index, which is 111. A PI111 soil has a taxable value of $352. “That means next year, no soils can change more than 10% — more than $35.21,” she says. “Even if the soil’s production says it should increase by $79 per year, the statute says it won’t change more than $35.21.”

That cap on movement is why even in a poor growing year with poor prices, farmland can still maintain or even increase its tax assessment rate.

“Over the past 20 to 30 years, values have been limited by that 10% growth,” Matherly explains. “Our income-earning potential has surpassed what the 10% limit allowed for, so now there has to be some catching up. It has to go up before it can come down in a bad year. And unfortunately, it’s at a time when the farm economy is weak.”

Don’t look for farmland tax assessments to change in Illinois. Matherly points out that land values are the most stable thing in a rural community, which means their taxes are the most reliable local government income. For example, relying on income taxes to fund schools would be difficult in a tough economy with higher unemployment rates. Consider what that would mean for a rural school that already has more than half its students qualify for free or reduced lunch, based on their family’s economic situation. The property tax burden says that it’s in the greater good to educate a society, and that’s beneficial to landowners.

“I don’t think there’s any way to get around the fact that Illinois relies a little too heavily on property tax,” Matherly says. But remember, the taxes you’re paying don’t go to the state: They fund services you want and need.

“Farmland owners want to know if they call 911 or their house is on fire, help will show up,” she says.

At the end of the day, the best thing farmland owners can do is make their taxing district accountable to them. When local government holds a truth in taxing meeting, show up.

You may be the only one there, Matherly jokes. But you just might come away with enough information to make those easy Illinois jokes more informative.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like