April 29, 2020

COVID-19 is causing us to experience events that have always been possible, just not yet observed. For farmers, these events may have a big negative financial impact, or they may not. The impact on each individual farm will differ depending on how that individual farm has prepared for rare, financially devastating events.

Preparing for unseen events represents a logical approach. We call this approach "stress testing." Just because you have not seen an event, it does not mean it does not exist. Or said another way, the absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

Why should a grower stress test their farm for events that have never occurred? The answer lies in your individual goals and objectives. If your goal is to farm next year, you must develop a plan to overcome financially devastating events (i.e. combinations of low prices or yields). How much revenue can you lose before going out of business? Preparedness is crucial for survival.

Related: Complete coronavirus coverage

Each farm is on its own financial path through time. So, each farm has a different wealth level and farm structure it would reach before it would go out of business. Individual paths exist as each producer has a different amount of working capital, level of mortgage payments, net worth, per-acre production costs, location, crops grown, practices (irrigated or not), etc.

Farm survival strategy

To develop a strategy that provides the highest chance of farm survival (i.e., not going out of business), one first must acknowledge that you may never experience a rare, financially devastating event. On the other hand, you may experience several of them consecutively.

As a result, one must view rare, financially devastating events through the eyes of probability and logic. For example, preparing for a financially devastating event and not experiencing one does not make the strategy poor — rather, different events took place, and you still achieved your goal of farm survival.

Planning for rare, financially devastating events does not imply forecasting them. It implies being prepared for an unknown future. No one can predict when a rare, financially devastating event will hit your farm. You, as the decision-maker, need to own your future with the decisions you make today.

Make your own future by owning your decisions based upon your instincts, logic and facts. Stress testing allows you to partially circumvent the complexity of markets as you are protecting your own farm, not trying to understand the how, when and why.

A number of combinations of variables you control can lead to farm survival in the face of a potentially financial devastating event such as COVID-19. There is not a "one size fits all" strategy for farm survival.

Everyone will find a unique combination of tools. Some of the variables you control are working capital, production costs, off-farm income, mortgage payments on land owned, equipment payments, wealth, crops grown and acres rented.

Knowledge of your exposure to rare financial risk also plays a pivotal role in farm survival. Since we are talking about rare, financially devastating events, events that lead to farm failure, we are going to focus on the area of low prices. For the corn market, we can take a probabilistic approach to identify where corn prices may end up this fall (see Figure 1).

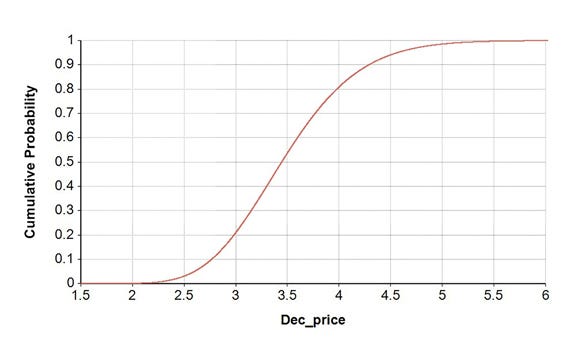

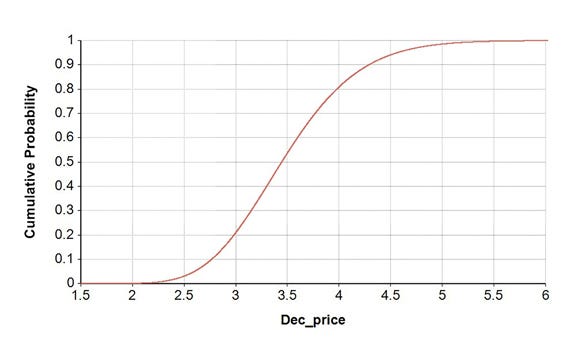

FIGURE 1: December corn futures cumulative distribution function. Source: Cornhusker Economics

Figure 1 contains the cumulative distribution function of December corn futures and describes the distribution of where December corn futures can end up on Dec. 1. Underlying the construction of this distribution is the current December corn futures and implied volatility, generated from the Black-Scholes formula that relies on market-driven data.

From this distribution we can identify the probability of where corn futures prices can end up on Dec. 1. There exists about a 10% chance that corn futures on Dec. 1 will be below $2.75 per bushel. To see this and calculate other probabilities, find your probability on the Y axis and go over to the red line where you then identify the price associated with that probability on the X axis — $2.75 per bushel for corn futures on Dec. 1 represents a drastically low value.

However, market tools such as loan deficiency payments and crop insurance will kick in, providing payments, thereby limiting any further downside price risk.

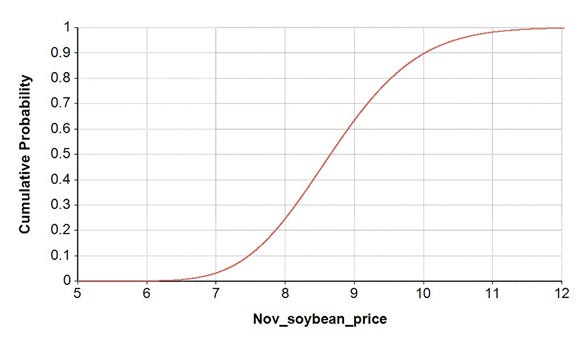

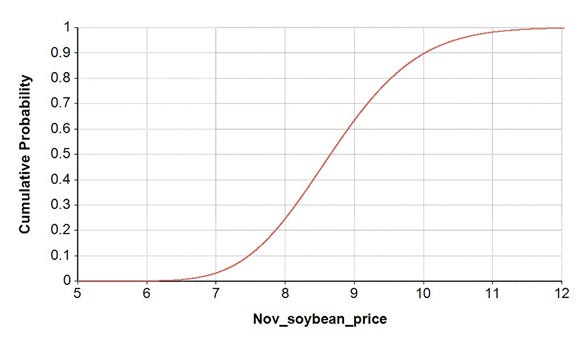

FIGURE 2: December soybean cumulative distribution function. Source: Cornhusker Economics

We follow the same logic used for corn in soybeans (see Figure 2). For soybeans, there exists a 10% chance of soybean futures being below $7.50 per bushel on Nov. 1.

For wheat, there exists a 10% chance of wheat futures being below $4.75 per bushel on July 1.

FIGURE 3: July wheat cumulative distribution function. Source: Cornhusker Economics

Relying on past experiences would tell us that prices found in this approach are not "real" since we have not experienced these prices. Essentially, these prices have been hidden. But we ask you now, as we are experiencing COVID-19 (plus everything else going on in the world), do you want to reconsider the possibility of where commodity prices can go?

COVID-19 has dramatically influenced the ethanol market, with ethanol plants shutting down or scaling back, as well as the feed market. Other crops have suffered larger impacts — potatoes, apples and fresh veggies, for example.

Take a portfolio approach

Ask yourself, "If the price is X and my yield is Y, how am I going to survive?" Stress test your farm by exploring how the decisions you already have made fare in various scenarios. Use the low prices identified above. Know what constitutes a financially devastating point for your farm.

Have hard discussions with your family or business partners about financial outcomes from bad events based upon your farm's characteristics. Walk through multiple scenarios, considering combinations of price and yield possibilities. Take the portfolio approach to calculating revenue by including all relevant sources of income (and their costs):

Contracted grain (preharvest hedging, option contracts, basis contracts)

Farm bill (PLC/ARC)

Loan deficiency payments

Crop insurance

Other possible government payments, such as MFP, paycheck protection loans, etc.

Each of these revenue streams calculates payments differently. Knowing how these function is important to understanding how you will be paid and when.

This portfolio approach to calculating losses from rare, financially devastating events needs to go beyond a revenue prediction. By diving deeper into the decision-making process, you can evaluate strategies for farm survival such as crop diversification, refinancing short-term debt into long term debt, contracting with multiple vendors, cashing in on soil fertilizer bank by applying less fertilizer this year, and diversifying capital sources.

The list can go on as each farm is unique. It is up to the individual producer to identify their optimal strategy to survive. This decision framework includes other tough decisions, such as letting go of things that will allow farm survival, which might entail getting rid of unnecessary equipment or leased land not performing as expected.

Once losses are calculated from multiple scenarios, it is then time to ask yourself if you have enough working capital to survive. Or, what will you do if one of those low price or yield combinations hits? Can you survive in these sorts of scenarios?

Now that you have identified low-revenue financial outcomes, do it over multiple years. Can you survive multiple years of low prices or yields? Setting yourself up to survive provides comfort in making long-term financial decisions when outcomes are unknown.

The next event may make COVID-19 look like a walk in a park. The key to survival rests in your farm's revenue portfolio when financial stresses hit.

Walters is an associate professor in the Department of Agricultural Economics at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Groskopf is a Nebraska Extension educator for agricultural economics. Preston is owner of Preston Farms in Hardin County, Ky.

Source: Cornhusker Economics, which is solely responsible for the information provided and is wholly owned by the source. Informa Business Media and all its subsidiaries are not responsible for any of the content contained in this information asset.

Read more about:

Covid 19You May Also Like