On Megehee farm: Attention to detail pays in producing quality cows

“The cattle business isn’t one that young people can readily get into, because it doesn’t provide cash flow unless you’ve got land and equipment," says Jacob "Jake" Megehee, Macon, Miss., producer. "But once you get everything paid for, cows will cash flow, and if you’re careful you can have a pretty good income.”

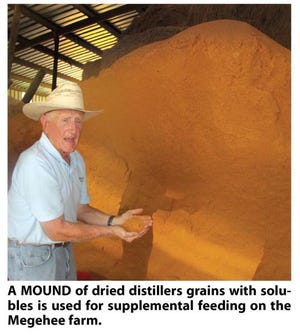

Jacob Megehee hops out of his pickup with a spryness that belies his 71 years, grabs a five-gallon bucket of dried distillers grains, and shouts across the pasture, “C’mon, babies! C’mon, babies.”

Cows leave their grass munching and shade loitering and come loping to him.

“They love this stuff — it’s like ice cream to them,” he says as he pours piles of the corn byproduct on the ground, then backtracks to the pickup for another bucketful.

Here in the rolling prairie land just outside Macon, Miss., he and his wife, Martha, operate Megehee Cattle Company, raising quality beef cows. They also utilize, as part of the cow-calf operation, a family farm in Pearl River County in south Mississippi where they both grew up.

“My family had a dairy/beef/hog farm on the edge of the Pearl River swamp,” he says, “and Martha’s family had a farm not far away; her father raised cattle and grew tung trees for oil used primarily in marine paints [a thriving industry in southeast Mississippi until Hurricane Camille, one of the strongest storms in U.S. history, wiped out most of the trees in 1969].

Jacob Megehee: From bull riding to Vietnam and back, the circuitous making of a cattleman

“I hunted small game and fished in the swamp,” he says. “I was in 4-H and FFA and got a degree in dairy production at Mississippi State University, thinking I’d make a living in dairy industry like my two brothers.”

But military service intervened and he spent seven years on active duty as an Army helicopter pilot, including a year in Vietnam, where he flew 2004 hours, received five Purple Heart medals, a Silver Star, a Distinguished Flying Cross, a Bronze Star, 27 Air Medals and an Air Medal With Valor device.

For three years, he flew Medevac missions all over Europe. It was during flights over Germany and the Netherlands, Megehee says, that “I’d look down and see beautiful dairy herds grazing on stunningly gorgeous forages. In the Netherlands, they had portable milking machines that they rolled into the field and milked cows right there. I got the dairying bug badly. But Martha, more sensibly, said she didn’t want me to be a dairyman, because we’d never have a life outside of milking cows.

“By the time my duty in Europe was nearing an end, we had a young daughter and $10,000 that we’d saved from my military pay. That money was burning a hole in my pocket to buy some farmland. But construction of the John C. Stennis Space Center had pushed land prices in our home county out of our reach.

“My older brother married a girl at Brooksville, not far from Mississippi State University, and I was familiar with the area from my MSU, 4-H, and FFA days. I knew these prairie soils could grow good forages.

“So, we looked around and bought this land, which we leased out while I was at Ft. Rucker, Ala., as a test pilot. We bought 93 steers and put them here, and we drove over almost every weekend just for the pleasure of seeing our cows on our land. We had horses, too, for our young daughter to ride.”

When his seven years of military active duty ended, Megehee started a master’s program at MSU, managed the university’s south farm, flew helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft for the university, and continued flying three weekends in the Amy National Guard. He served in reserve components for 22 years, retiring as a full colonel.

'Bigger is not always better'

“We put a double-wide trailer here on the farm and I told Martha if we were able to make a living, I’d build her a house. And with a carpenter and a little outside help, we later built this place. She did all the painting, staining, and decorating, and has planted and looked after all the roses and flowers. She has turned a hillside pasture into a beautiful yard and home.”

After completing his master’s degree in ag economics and moving into a Ph.D. program, Megehee says, “I was working full time for the university, flying three weekends a month in the National Guard, and by then we had 200 cows here on the farm and three children. I was just burned out.”

He took a teaching position at East Mississippi Community College, “a welcome respite, allowing me to devote more time to the farm, while still flying in the Guard.”

The farming enterprise grew, and at one point they were renting another 1,100 to 1,200 acres, growing soybeans, milo, and wheat, and had a 600-head cow herd.

“But bigger is not always better,” Megehee says. “We were working ourselves to death. In 1986 we quit row crops and cut cow numbers to what we could comfortably handle with a little outside help. Now, we’re strictly a cattle operation.

“All our cows, some with Charolais blood, are bred to black Brangus bulls from Cow Creek Ranch, a nationally-known cattle operation at nearby Aliceville, Ala. We decided to work with Cow Creek because the demand in the industry is for black hide cattle. These cows have easy calving and put live calves on the ground. We’re now into our eleventh year of Cow Creek genetics.”

He moves 55 or so 500-pound heifers to their south Mississippi farm in the fall, “and if things go right, we’ll bring back 900-pounders.

“We sell the black bred heifers at the Cow Creek auction. They handle marketing and promotion, and our heifers have gone all over the Southeast and out to Texas. We also do video marketing through Superior Livestock Marketing (American Rancher), which allows us to reach a wide audience. They have a national advertising program — and in this business you need to get your product before the buyer.

“Our black and white crossbred heifers go to the August sale at Hattiesburg, Miss., and our bred heifers are sold at Cow Creek and at Hattiesburg. The last two years, our heifers have beat the top selling prices of the big commercial sale at Uniontown, Ala., and for five of the last seven years, our 2 to 2-1/2 year old commercial heifers have topped the Cow Creek sale. This past year our heifers averaged $1,677 in two sales. That’s a pretty fat price, and I think this year we could see around $2,000.

“We like to use our own stocker steers, but we’ll also buy some at the sale barn or locally. We start with 300 pounders in the fall and when we get them up to 750-800 pounds, we’ll sell them in truckload lots via video auction. “We’ll put about 70 steers in the Home Place video auction at Hattiesburg in August. We like to put together a load of steers (approximately 50,000 pounds total) all the same color, with 100 pounds or less variation from lightest to heaviest. Last year, our big steers averaged 866 pounds.

“We really like video auction marketing — it saves time, there’s much less stress on the animals, and we can choose our delivery date.”

In February, Megehee says, “We’ll have some steers that would be too big for delivery in September, so we sell them through Prairie Livestock, Inc., at West Point, Miss., when they need to fill out a truckload.”

At mid-June this year, the Megehees had 125 mama cows with their calves, 55 bred heifers, and 90 steers on their farm at Macon and another group of heifers on their south Mississippi farm.

Prairie soils 'really grow grass'

“We have 329 acres here and lease another 124 acres for steers,” he says. “These prairie soils will really grow grass. I have one field that’s been in Marshall ryegrass since 1986 and has continuously reseeded itself each year. There’s a lot of dallisgrass,, common bermudagrass, and five varieties of coastal bermudagrass on pastures. In south Mississippi, I depend on bahia and common bermudagrass, plus crabgrass behind ryegrass.

“I plant ryegrass on a prepared seedbed, and like to start the breeding heifers on it in January when I bring them up from south Mississippi. If there’s enough ryegrass for them to graze just one hour a day, it’s like a magic potion because they start their estrus cycle immediately.

“I’ve tried five varieties of coastal bermudagrass, but it’s costly to keep up because it requires expensive chemicals and excessive fertilizer. I’ve also tried some of the new fescues, but they just fade away when summer heat sets in. I’ve pretty much got to the point that I soil test, lime and fertilize the pastures, and am happy with whatever comes up.”

Megehee serves on the advisory board for the Mississippi State University Northeast Mississippi Producer Steering Committee and is chairman of the Beef Committee.

“Among our recommendations to the university is that we need development of a good cool season perennial forage grass that can survive our summers,” he says.

“We also desperately need a summer perennial legume that needs no nitrogen. Durana clover is a good forage, but it quits growing in the summer heat. Lespedeza also warrants some consideration.”

The dried distillers grain with solubles that he uses as supplemental feed is a corn byproduct from ethanol production. “It’s 10 percent fat and 28 percent protein, and the cows love it,” he says. “The price varies with the price of corn — the last load was $276 per ton delivered from Hopkinsville, Ky.

“I put up a lot of hay, about 500 round bales that weigh 1,400 pounds each. Our mama cows eat hay starting about Thanksgiving and continue until mid-March. I nutrient-test my hay and supplement it with protein and/or energy as required.

“I have about 300 rolls of hay in reserve in the barn that I’ve had since 1986. It’s still high quality, 8.5 percent protein and 53 percent total digestible nutrient, and has good color. If we have a horrible hay year, as we did in 1986, I can fall back on this reserve.”

Megehee has used hen litter on pastures for the last 10 years, applying 2 tons to 4 tons per acre. “It provides about 1 percent nitrogen, 3.6 percent phosphorus, 2.2 percent potassium, and 3.9 percent calcium,” he says.

“But with that fertility, I can also count on a lot of weeds. Horse nettle is a big problem, and we get foxtail and barnyardgrass. I’ve worked hard to get clover in the pastures, but I have to wait until it becomes dormant before I can spray the horse nettle.”

All breeding age females are pregnancy checked each fall, and heifers receive a pelvic area evaluation. “Experts say if a cow doesn’t breed, it should be sold,” he says, ��“but I believe in giving them a second chance. I’ve got a number of good calves from ‘second chance’ cows, and often the cows will then get back on a regular breeding schedule..”

All of Megehee’s bulls get a breeding soundness evaluation each year and bulls are culled if necessary. He never names his cows — “It makes it too personal ”— but he knows each one, it’s pedigree, and how it’s performing. He uses ear tags with numbers and an elaborate ear notching system to track when calves are born.

Input costs outpacing beef prices

Beef prices are very good now, he says, “And that’s good — but our costs have shot up too. Ammonium nitrate, for example, is now over $525 per ton. There has always been a rough rule of thumb in this business: How many 500 lb. feeder calves does it take to buy a pickup truck? And that number has kept going steadily upward. The price we’re getting for our cows hasn’t kept up with the price of our inputs.”

However, Megehee says, increasing land values help offset some of the inflation in other prices.

“Many farmers charge a 3 percent to 4 percent opportunity cost for land. But land value usually increases that much or more — which is good, considering you’d be hard pressed these days to get 1 percent on a bank CD.

“That’s one reason land prices are going up and people are investing in farmland. Even this black prairie land is bringing $3,500 to $4,000 an acre — if you can find any for sale.”

Megehee is vice president of Mississippi Cattlemen’s Association and he and Martha travel to meetings all over the state, as well as to national meetings and events.

He’s also on the Mississippi 4-H Foundation board. “It’s a joy to see so many smart, talented young people doing agriculture projects and thinking about careers in agriculture,” he says.

“The cattle business isn’t one that young people can readily get into, because it doesn’t provide cash flow unless you’ve got land and equipment. For most people in the cattle business, that’s their second job — we’re mostly a bunch of old folks. But once you get everything paid for, cows will cash flow, and if you’re careful you can have a pretty good income.”

He cautions, though, “Cows are like row crops — you’d better have a marketing plan before you put the first cow in the pasture.”

Cows are “ like a savings account on hoof,” Megehee says. “If you need new tires for the pickup, or a new fridge for the house, you can take one or two cows to the sale barn and walk away with cash. And you can run cows on land not suited to row crops.

"But, you’ve really got to love cattle to stick it out in this business, because invariably they seem to get through fences when you’re on your way to Sunday School or to an important meeting. Martha has received calls from the Sheriff’s Department late at night when I was away, telling her that black cows were on the highway near our farm.”

Megehee also serves on the Beef Board, which handles the $1 checkoff fee that’s paid every time a cow changes hands.

“It brings in about $800,000 a year,” he says.“About half of that stays in the state of Mississippi to promote beef.”

He has led a crusade for a statewide additional $1 checkoff to promote the beef industry, which must be approved by the legislature before the state’s 17,000 beef producers can vote on the measure. He hopes to continue an education program “to get producers proactive on beef issues instead of continuing in a reactive mode.

“This money could be used for research, education, youth programs, and any other imaginative means to promote our beef industry,” Megehee says. “The money would be removed from the proceeds at the sale site and could be refunded to the seller by written request to the Beef Board. The additional $1 would be completely voluntary for each producer.

“It’s something that’s very much needed, because research has shown that each $1 invested returns $5.55 to the beef producer.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like