More than once, the point was made if you suspect that someone is thinking of killing themselves, ask them if they are.

You will not put the thought into their head. Your words will not cause them to take action. Rather, your attention shows that you care, that you hear them and that you want to help.

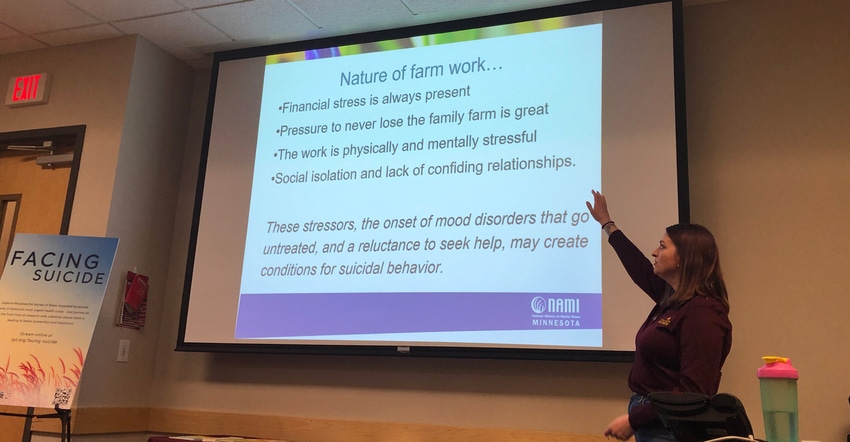

Those were the messages shared during an event hosted Oct. 11 by Twin Cities PBS and the Minnesota chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Health Illness (NAMI). “Facing Suicide: Suicide Prevention Education and Stories of Hope for the Agricultural Community” was held at St. Cloud State University.

The session focused on suicide prevention training and highlighted the unique stressors faced by the agricultural community. Emily Krekelberg, University of Minnesota Extension farm safety and health specialist, provided training in QPR, a national suicide prevention education program that focuses on three actions to take: Question, persuade and refer.

“QPR is not intended to be a form of counseling or treatment,” Krekelberg said. “QPR is intended to offer hope through positive action.” NAMI worked with the Upper Midwest Agricultural Safety and Health Center to create the ag-specific programming, she added.

Krekelberg noted several stressors specific to agriculture that can cause severe depression in farmers. Those include the loss of the farm, health crises and injuries, weather-related losses, machinery breakdowns and loss due to livestock diseases.

“To a farmer, the land is everything,” she said. “Losing the family farm is the ultimate loss, bringing shame to those that let down their forebearers and dashing the hopes for successors.”

She shared several myths and facts about suicide:

Myth: No one can stop suicide. Fact: If someone gets help, there is the probability that they will never be suicidal again.

Myth: Confronting a person will make them angry and increase the suicide risk. Fact: Asking someone directly lowers their anxiety and the risk of an impulsive act. It opens communication.

“Suicide is everyone’s business, and anyone can help prevent it,” she said. If a person gets angry because you brought up the topic of suicide, so be it. Krekelberg said one farmer told her that he would rather have a friend get mad than to lose the friend to suicide.

Myth: Someone considering suicide keeps plans a secret. Fact: Often, a person thinking about suicide communicates their intent during the week prior.

Myth: Those who talk about suicide don’t do it. Fact: People who talk about suicide may or may not complete it.

Myth: Once a person decides to complete suicide, there is nothing anyone can do to stop it. Fact: Suicide is the most preventable type of death, and almost any positive action may save a life.

“Suicide is preventable,” Krekelberg said, adding that it is critical that all suicide clues and warning signs are taken seriously.

Help helps

Be alert for direct or indirect verbal clues (“I’m going to kill myself” or “Don’t be surprised if I die in a farm accident”). If you hear this, say something. Be on the lookout for behavioral or situational clues (depression, substance abuse, mood changes; job loss, loss/death in family, terminal illness diagnosis).

“Trust your gut,” she added. “Say something right away.” Research has shown that people who attempted and survived suicide said they attempted it within an hour of saying so.

Krekelberg then delved into the QPR process — question, persuade, refer. First, however, she said someone who is intent on helping must first have a support network in place to help the helper in a crisis.

“This is not something you can do on your own,” she said. Make a list of individuals and mental health resources that you can call.

QPR focus

The “question” part of QPR sets the stage for learning about the person. You can ask direct or indirect questions to start the conversation. Have you been unhappy? Do you wish could go to sleep and never wake up? I’m worried about you and wonder, are you are thinking of suicide?

Do not say, “‘You’re not suicidal, are you?” or ‘You won’t do something stupid, will you?’

“Those questions are begging someone to say no,” Krekelberg said.

If the person says yes to thoughts of suicide, your next QPR step is to persuade them by words and actions to stay alive. First, listen to them and give them your full attention. Do not judge or give advice. Tell them you are sorry things are so hard. Do not guilt them into staying alive by saying they have lots of live for, like their children or business.

“Say ‘I’m so glad you told me. I want to help you get through this,’” Krekelberg said. “You could even say ‘I want to live.’”

Eventually ask them if they would go with you to get help, or allow you to get help. If they decline and say they feel better after talking with you, respond by saying, “Let’s still talk with someone.”

And this leads to the last step in QPR — refer. Ask the person who else may help them — a therapist, family doctor, friend, member of their faith community — and make calls. Have additional resources handy on your cellphone — county crisis team; suicide hotlines such as the new 988 number; mental health counselors; and police, if they have mental health training.

And finally, if the situation is extremely serious — the person has a gun, or you are in danger — immediately call 911. Tell the operator that the person is suicidal and ask for a mental health crisis team or an intervention specialist.

Effective QPR doesn’t end with “refer,” Krekelberg concluded.

“Follow up with visits, calls or cards,” she said. “Treat the person the same as you would if it was any other illness.”

The film

Short clips from the new PBS show, “Facing Suicide,” were shown at the St. Cloud event. The 83-minute video, which can be livestreamed, highlights stories of people across the U.S. whose lives were impacted by those who died by suicide and by those who were thinking of dying by suicide.

Researchers also discuss their work to help us to understand suicide and how to help. There is a segment focused on a farmer who was suffering from severe depression. His wife called a psychologist, who immediately came over and helped the farmer get the proper treatment.

Throughout the film, stories shared focus on recovery, resilience and hope. Some communities have stepped up with grassroots suicide education campaigns.

Watch the video at pbs.org/show/facing-suicide.

Crisis help

If you or someone you know is experiencing a mental health crisis, help is available via phone call, text or online chat.

Texts or calls to these numbers will connect you to a crisis center where trained volunteer counselors or mental health professionals are waiting to help. Calls are free and confidential:

988. Call or text. Chat at 988lifeline.org/chat.

Mobile Crisis Teams in Minnesota. **274747 (from mobile phones)

Minnesota Farm and Rural Helpline. 833-600-2670; text “FarmStress” to 898211

The Trevor Project for LGBTQ Youth. 866-488-7386; text “start” to 678678. Chat at thetrevorproject.org/get-help.

Call 911 if there is immediate danger to you or someone else. Stay calm and tell the dispatcher, “This is a mental health emergency” and ask for a mobile crisis team. If a mobile crisis team is not available, ask for a crisis intervention team. Be prepared to share information about mental health history, diagnosis, triggers, what has worked in the past, details of the current situation and more.

For nonemergency mental health information and support, call the NAMI Minnesota Helpline at 888-626-4435.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like