March 3, 2017

Almost twenty years ago, I had brain surgery to install some new equipment. The surgery is called Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) and basically has a small pacemaker in my chest that sends signals via an electrode running underneath my skin, to my brain. Those electrical impulses override uncontrollable tremors I've had for most of my life. The medical condition for those tremors is called Essential Tremor. Estimates put the number of people with Essential Tremor at somewhere between 7 and 10 million. Medications can control the tremors for many people, but surgery is an option for those people whose tremors either aren't controlled, or the side-effects of drugs are worse than the tremors.

The first person to undergo this new procedure as part of a research trial in Des Moines, Iowa, in 1997 had both TV and print reporters cover his surgery. That's how I found out about it. That's also what led me to pursue the surgery in Des Moines later in 1997.

Everything was set up for a March 1998 surgical date. The results were impressive. What is most unusual about this procedure is that the patient remains awake while the surgeon drills a hole in the skull and places an electrode into the brain. The patient then does a few activities like holding onto a cup, or writing their name on a clipboard, to see if the tremor is controlled without any side-effects. We're talking about a matter of millimeters here for the target area. If the electrode is a millimeter or two off, you won't see great results. When it's on the money, the tremor control can be breathtaking.

That's how my first surgery went. A surgical mask could not contain the smile of my neurologist, or the gasps of others in the operating room when we found "the spot."

A local TV station in Waterloo, Iowa, did a story about my surgery a couple weeks after I had my device programmed and put into regular use. Heather, the reporter, did a wonderful job with the story. She and I talked about our hope to find just one person with the story and help them.

Getting a little television coverage aimed to help others – helped more than 138.

It didn't take long for me to find people who were interested in the procedure. Heather and I stayed in touch after the story aired. When it was time for me to have another surgery to put a second system in to control tremors on my other side, Heather and I talked about the possibility of having cameras in the operating room to film the whole thing. My doctors were okay with the idea, so we went ahead and made the second DBS surgery a production. That story was so well-received that we kind of blew past the original goal of helping one other person. Heather and photojournalist, Denny, did such a good job that I was able to share the various clips with other potential prospects. The headcount today stands at 138 people who went ahead with surgery after getting in touch with me.

Around the same time, I sent some comments to Medtronic, the maker of the DBS device, via their web site on a Friday night. Someone from Medtronic replied yet that weekend and asked if it would be okay to share my comments with others at the company. I was fine with that. Someone from Patient Services got in touch and asked if I'd be interested in writing a testimonial letter.

I decided to write a letter, but it wasn't easy to write it to a faceless company. While I thought about it, former staffer (and Trusty Sidekick) Lorne passed along a copy of Business Week magazine to me. It had a story about my device and the executives at Medtronic who made it happen.

Now I had names and faces for my letter. That's when I decided to send my letter to Bill George, the CEO of Medtronic at the time. That letter opened up a bunch of opportunities for me with Medtronic. I was invited to visit the company and had the chance to meet a bunch of people, many of whom remain friends to this day. That experience and that letter also brought the opportunity to speak at several Medtronic events.

One of those events led to a team of video folks coming to the farm in 2002 to shoot some day-in-the-life footage of me as I went about daily life with my rewired brain. The crew was pretty much all urban with no farm experience. I explained what we did on the farm and how certain pieces of equipment worked. Then I actually did stuff with that equipment.

When we were done with our work after a day or two, the crew was ready to head back to their big city lives. We had done an interview and shot some footage of me using a device to turn my stimulator on and off. Prior to that day, I had used a giant magnet that Medtronic gave each patient. When I say giant magnet, I'm talking both size and power. With two devices, I had two magnets. The best response I ever got from an audience when showing them how my stimulator worked was my niece's second-grade class. I put one magnet in the palm of my hand and told the kids how strong it was. Then I took the second magnet and put it against the backside of my hand, where it remained after I pulled my hand away.

The second-graders were blown away.

The new device that the Medtronic crew had with them was more like a TV remote control. It had a few buttons on it to turn my stimulators on and off, as well as check on the battery status to let me know if it was nearing the end of its life.

The pacemaker is very similar to a cardiac pacemaker. That means it runs on a battery. My typical battery life has been three or four years. When the battery is getting close to the end of its life, I have anywhere from a few days to a few weeks to get it replaced. This new remote would do a much better job of informing me ahead of time. My old magnet system simply wouldn't turn my device on it when the battery died.

Technology changes a lot. Few people reach retirement age after having only one job their whole career. Combine those two things and you will find that many of those friends you knew at the company had moved on to other things. Their replacements weren't always filled in as to who everyone in the giant Rolodex of life at Medtronic was.

My brain surgeon also retired from doing this procedure. He was not replaced. That meant I had to go elsewhere for surgery when it was time to do more work on my brain in 2009 after getting a staph infection in an electrode. The DBS system for my left hand had to be removed and re-implanted a few months later. I found a new surgeon at a hospital much closer than Des Moines and got my hardware issues handled.

Fast-forward to last fall. The stimulator for my right hand was sending enough of an uncomfortable sensation down my face and arm that I figured something wasn't right. I made an appointment with my new Neuro team to take a look.

We didn't find anything obvious as far as wire breaks or other glaring issues. There was also the fact that both of my batteries were now run down enough that they could be replaced. The plan was to replace both batteries and re-position the lead wire that was giving me problems.

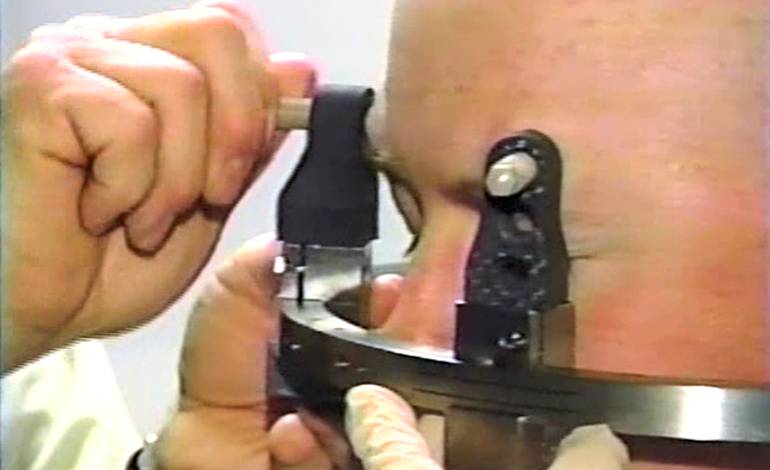

Sounded fairly simple. What the medical team failed to take into account was my past history. This surgery requires me to get a stereotactic frame placed on my head. That is held on with screws. Those screws are torqued down against my skull. It's not terribly comfortable. The first time I had it placed, both syringes for the anesthetic went past my eyes at the same time. They looked to be huge needles from my angle. A few seconds later, they also felt like huge needles.

To add to the fun, the original surgeon used a hand-crank drill to bore through my skull instead of a high-speed dental drill like most surgeons use. A slower drill speed allows the patient to have an audio experience that is nearly unrivaled! This was beyond fingernails on a chalkboard for me. It was Dolby Surround Sound like I had never experienced before.

When medical duct tape won't do, surgeon uses hand-crank drill to secure frame to Guy No. 2's head.

I ended up having the frame put on multiple times for a few different surgeries. It never ended up being enjoyable, so my preference was not to have a frame put on again. I wasn't able to negotiate that option in 2009 with the new surgeon, but this round was different. He'd be willing to let me be out cold for this procedure if I was willing to take the chance that my results couldn't be tested while I was awake.

PS, when the old wire is "re-positioned," that's a nice way of saying that it's going to be yanked out and a new one put in its place. This isn't a spark plug wire or a hunk of electric fence wire we're talking about. It's an electrode that has been in my brain for 18 years. The odds of it popping loose without any medical-grade WD-40 or Knocker 'er Loose being involved were slim. The odds of it causing a stroke or a brain bleed of some kind were higher than slim.

The risk-reward math looked kind of obvious to me: Load that I.V. up with the good stuff, Doc, and keep the TV remote within reach when I get back to my room after surgery! If you're going to stroke me out with the wire work, I think I'd rather code on the table while I'm out than be awake for it.

The Good Doctor was okay with that. He gave me the phone number to call that evening to get my time for surgery the next morning. To keep it interesting, I couldn't call until around 8:00 that night. The weather was going to be a challenge. We were under yet another severe weather advisory that night. Blizzard conditions with a foot of snow were expected. What would normally be an-hour-and-change of travel time could be either several hours or completely impassable. That's when I decided to skip the commute and stay in town after all of my pre-op stuff was done. I already had my cousin, Jason, lined up to do my chores. Adding one more day to it wouldn't be impossible.

Sure enough, my time to show up the next morning would be a casual 9:00 AM instead of the usual 5:00. I went to the front desk at the hotel the next morning and found that the shuttle to the hospital just left two minutes before that. The next one would arrive at 9:12.

So I walked a couple blocks to the hospital and showed up early. My surgical date could have been a week earlier when I had my initial appointment a few weeks before. The surgeon's nurse was looking through his schedule and we thought the previous week sounded good. Then she looked closer at the schedule and said, "Oooohhh, he already has two DBS surgeries that day. He doesn't like it when I schedule him for three in one day."

Yeah, well, I want my brain surgeon fresh and happy when he shows up, not stressed and crowded for time like I'd shown up at his repair shop at 4:56 on a Friday afternoon with a head gasket I had to have fixed yet that day! Let's pick a different day.

The nurse was fine with that, as long as I was willing to wait.

Fresh. I want him really, really fresh. I'll wait.

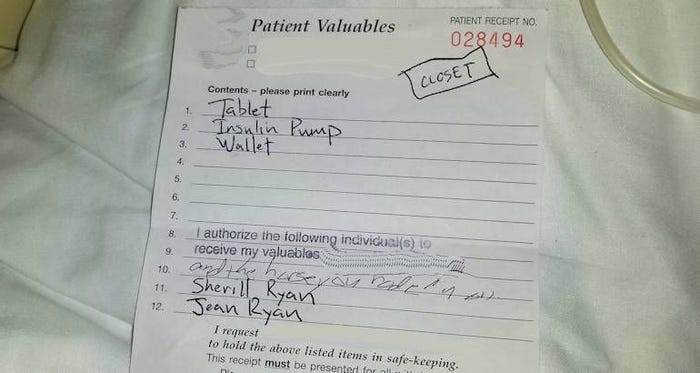

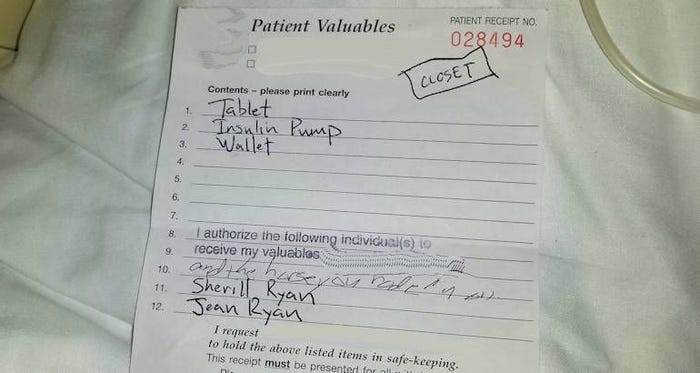

The pre-op staff got me prepped for surgery. It took a lot longer than any of the other surgeries I'd had in the past. The other thing that surprised me was the fact that I had to hand over my insulin pump. They would keep it in a safe with my wallet and the iPad I brought with me. My blood glucose would be handled entirely by I.V. in the meantime. Seeing as how the endocrinologist I see at this facility seems to have no experience with the Continuous Glucose Monitoring System I use with my insulin pump, I figured no one on staff would know how to run my pump while I was out cold anyway. We then had to make another trip down to the hospital front desk to turn over all of my valuables to the security desk. I was given a form to sign with the names of whomever I chose to be entrusted with my wallet, my iPad and my pump when they came to get me after surgery.

After an incredibly long wait, I was finally wheeled into the operating room and introduced to the staff. The rep from Medtronic had only worked for them a couple of years, so I tossed out a name or two of people I knew (who either used to have her job, or were further up the food chain.) Next thing I knew, the anesthesiologist put a mask on me and told me that what I was inhaling was just oxygen, and he wanted me to take four deep breaths.

I've had oxygen before. This was not oxygen, but I only remember taking the second breath of it, so I didn't get a chance to debate content with the gas sommelier.

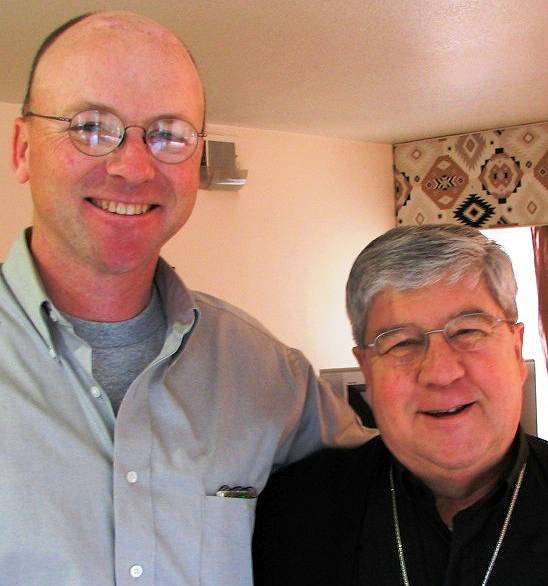

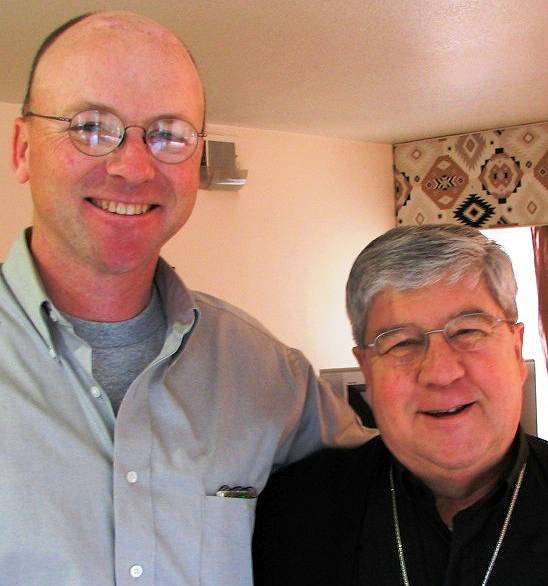

One of my friends from the bike ride across Iowa -- RAGBRAI -- that I met 20 years ago became a minister late in life. He's gone now, but he was a first-rate character and a true friend. The Right Reverend Bob Dew had his clerical collar on when he stopped to see me after one of my early surgeries in Des Moines. Bob used that collar to his advantage and weaseled his way into Recovery to see me as I came to after surgery. All I remember when I began to wake up was a really, really bright light in front of me and some guy with a clerical collar on, looking at me.

Hmmmmm....well, I guess this is St. Peter and I died during surgery.

Right Reverend Bob Dew used his collar to bend the rules and see Guy No. 2 after one surgery.

"Grillmaster, you gonna be steady at the grill now?" Bob asked with a smile.

Whew! Unless St. Peter is doing material at the pearly gates, I think I survived. That radio-quality voice sounded like Bob, but the light was too bright for me to see. Bob moved to the side and then I was relieved and thrilled to see it was him.

Bob reached for his neck and whispered, "I'm probably not supposed to be back here. The collar opens a lot of doors if I play my cards right!"

Yep, that was Bob alright.

There was no Right Reverend Dew for this round of surgery. In fact, I was already in my hospital room when I started to comprehend anything. It was somewhere around 8:00 at night. That's when the hourly visits for blood glucose checks began. The nurse would tell me what my blood sugar was and I'd tell her how much insulin I needed. She would then look at the chart and tell me she could only give me half of that amount, based on their math. We had the math discussion for two more visits before I decided they weren't going to take my advice. I proceeded to not sleep at all that night, thanks in large part to higher-than-normal blood sugar levels. But what do I know? I've only been a Type I diabetic for 45 years, on an insulin pump for 16 years and a Continuous Glucose Monitoring System for eight years. They had charts and graphs.

My surgeon showed up the next morning at an unusually early time. Sherill told me I'd be lucky to get out of there by noon. The Good Doctor was there around 8:00 and signed off on everything I needed to be set free. All that was left was my insulin pump and the staffer from Diabetes Care. She was surprised to find out that I didn't have my pump on and running yet.

A call was placed to the security desk downstairs to ask them for my pump. They refused. A staffer was then sent to get my pump and bring it back to my room so that we could proceed with my paperwork.

The staffer returned to inform us that my pump would not be released. Her name was not on my approved list of trusted advisors. Another call was placed. The importance of and relative-food-chain-heirarchy-level-by-comparison-to-you-guys-in-security was reviewed with the Security staff by the Diabetes big cheese.

No dice. I hadn't put this younger staffer's name on my form, so I wasn't getting any of my stuff until either of the two named people on the list showed up and provided an I.D. as proof that they actually are who they are.

How about if we add the staffer's name to my form and then she can get my pump? That was acceptable to the Security folks, but it required more trips back and forth to my room.

That's when genetics kicked in for me. The ornery German that makes up the majority of my DNA was coming to a boil. There was just enough jolly Irishman to take the edge off, though. I asked the young staffer for the form with the names on it. There were two lines left on the form between where the Security staff had stamped "I authorize the following individual(s) to receive my valuables:" and the space where I put my sister's name and Sherill's name. I added the young staffer's name on the one short line and then filled the next blank line with the following:

"and the horse you rode in on"

Proof of the problem with getting the pump back – it does say "and the horse you rode in on."

The youngster's eyes got kind of big when she looked at the newly-enhanced form. It wasn't quite what she expected. She stifled a laugh as she turned around to head down to the front desk again.

My insulin pump came back with her this time. Message delivered.

Sherill got there a bit later and took me home. My wheelchair driver stopped at the front desk with me to get my wallet and my iPad on the way out. Nothing was said. It didn't need to be. My stuff was handed over silently. There were no warm fuzzies to be seen or felt.

I returned a week later to get my new device programmed. They had actually turned on the device for my left hand while I was at the hospital, since we knew what the settings were for that side. The right hand, though, was going to be a whole new ballgame. Not only that, but it was all new hardware for me to navigate, too. That meant a more involved appointment with the programming nurse.

One of the meetings I'd had with some Medtronic engineers years before dealt with the concept of the remote I had been using until that day. It replaced the old magnet system and came to market in about 2002. My hardware replacement in 2009 used the older battery, so my 2002-vintage remote worked fine with that. Now I had new hardware and needed a new remote. The new remote has a digital display and lots of buttons, so it's clearly way better than the previous model. We're talking Ultra-HD vs. black and white TV here. It's pretty much 2017 vs. about 1974.

One of the medical residents who worked with DBS came in to my appointment. My programming nurse introduced her to me and quickly followed that with, "He has a remote you've probably never seen before! Show her, Jeff."

I held it up and you'd have thought it was something from the collection of Indiana Jones.

"Woooowwwww! I've never even heard of these!" the resident said with complete amazement.

That's when I thought about pointing out the fact that is a wireless remote, but I figured the concept of a wired remote would be way, way too retro for this millennial to comprehend. The whole VHS/Beta thing may put me in the 1800's steam engine category for her. I kept my mouth shut about my antique status.

The programming nurse and I finished our work. We would make some adjustments to the stimulator settings and I would hold onto a plastic bottle of Diet Coke to see if the fizz showed up. That's a trick we learned years ago in Des Moines. You can put a metal spoon in a ceramic cup to see if the tremor is controlled, but it's not easy to measure small differences in the tremor by the change in sound. A bottle of liquid makes for a visual that is easy to see when you hit the sweet spot. Even the slightest tremor will generate some ripples in the Diet Coke. If you see fizz, there is a lot of work left to do.

By the time we were done, the Diet Coke in my right hand was perfectly level. The programming nurse used one other measure she didn't mention.

"I knew it was getting much better. I could see it in your smile!"

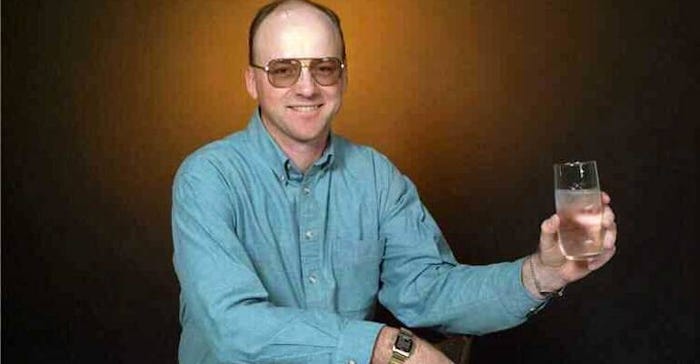

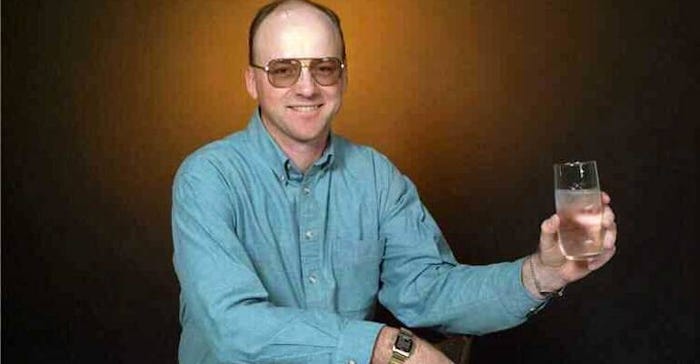

She was right. After my first device was programmed in 1998, Medtronic asked for a photo to use for publicity purposes. I stopped at a photographer's studio in Des Moines and had what she felt was an odd request. I wanted my picture taken as I held onto a glass of water.

Holding that glass of water – for a portrait – without a single tremor. Back then water was fine, now Diet Coke does just fine.

The photographer was more than a little skeptical. That's when I pulled out my magnet and gave her a demonstration of ON vs. OFF. Things made a whole lot more sense to her then. It turned out that she remembered seeing the story on TV and in the newspaper about that first patient a year before.

DBS doesn't cure my condition. It helps me to manage it. The fact that it does so in such a tremendous way is what makes all of the surgery worthwhile, and why it was fun to help others along the way. The little things in life return. Holding onto a full glass that stays quiet the whole time is more enjoyable than most people will ever realize.

One of the patients who went ahead with surgery gave me a report afterwards. "I went to dinner after the programming. They brought me a full drink and you know what? I never opened the straw, Jeff. It stayed in the wrapper the whole time."

I know the feeling. That's what keeps me smiling.

Guy No. 2

You May Also Like