Dr. Stephen Higgs isn’t the kind of guy who can be content with assuming he knows how a virus will behave.

After more than 30 years of working with zoonotic diseases, many of them vector-borne, he knows a great deal about how mosquitoes spread Zika virus, West Nile virus, dengue fever, yellow fever and dozens of other diseases. When he read the literature from the World Health Organization stating it was “unlikely” that SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, could be spread by mosquitoes, he wanted scientific proof of that.

Related: Complete coronavirus coverage

“The rationale that mosquitoes can’t spread it made sense, but nobody had actually done the experiments to test that. I couldn’t help but think ‘what if we’re wrong?’ The consequences of making a mistake with that assumption would be horrific,” said Higgs, who is the associate vice president for research and director of the Biosecurity Research Institute at Kansas State University. “I knew that right here at K-State, this lab had the capability of completing the experiments that would verify that assumption. So, we undertook to put together a series of experiments to see if this particular virus could infect and replicate in the species of mosquitos most likely to be carriers of viruses.”

Now, it has been scientifically proven that mosquitoes cannot be a vector for the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 because that virus cannot replicate in the insects the way viruses that are mosquito-borne can. Higgs and the researchers who participated in the study, Yan-Jang S. Huang, Dana L. Vanlandingham, Ashley N. Bilyeu, Haelea M. Sharp and Susan M. Hettenbach, had their results published July 17 on Scientific Reports at nature.com.

Inside the research

The first requirement for the study, Higgs said, was a supply of mosquitoes. Those are grown in-house at BRI. The SARS-CoV-2 experiments were conducted on three widely distributed species of mosquito: Aedes aegypti, Ae. albopictus and Culex quinquefasiatus, representing the two most significant genera of arbovirus vectors that infect people.

“We grow a lot of mosquitoes. I’ve been growing them in colonies for years,” Higgs said. “The ancestors of these were all collected in nature in various places. I even have one that is named for me — the Higgs white-eyed mosquito — that originally came from Puerto Rico. They’ve been happily moving around with me for decades.

“Basically you just add water. You do have to feed the adults on blood. We use artificial blood meals and maintain them in big cages. We breed them year-round and maintain them in one secure rearing room. When we are ready to use them, we put them on ice to immobilize them, count them and transfer them to the secure insectary inside the lab.”

He explained that the way a mosquito spreads disease is by first feeding on the blood of an infected person or animal. That blood is digested in the midgut of the mosquito, and the virus replicates and is disseminated to other organs in the hemocoel, notably the salivary glands. When the mosquito feeds on a naïve host, it pumps saliva into the puncture to prevent the blood from coagulating. The virus in the saliva is what infects the next host.

You can watch Higgs explain how an infection occurs in the video below.

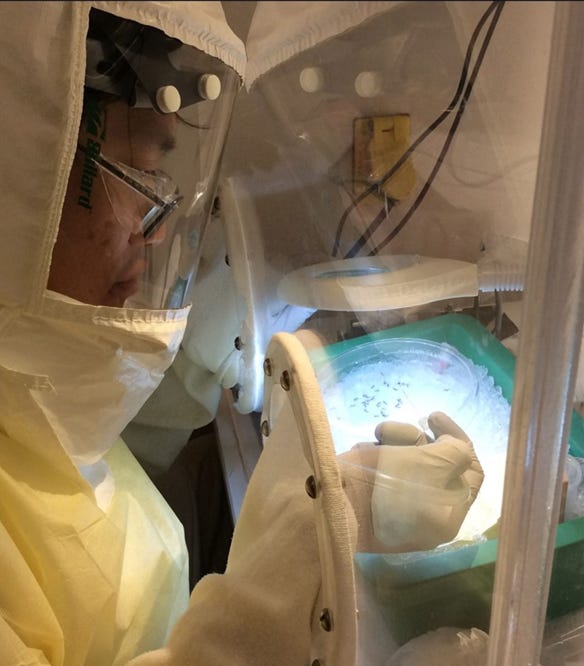

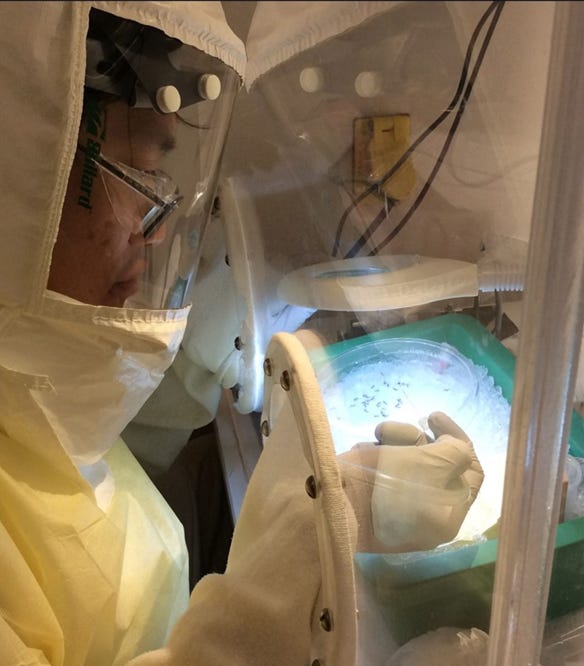

In the laboratory, the fun job is actually injecting them one at a time with the inoculant that contains the live SARS-CoV-2 virus. That task is accomplished by a scientist in full personal protective equipment, including a battery-powered air purifying respirator and multiple layers of clear plastic, reaching gloved hands into a plexiglass box to inject the viral material into the right spot on the mosquito. In this experiment, they placed it directly into the hemocoel, a method that would allow even non-vector mosquitoes to be infected.

“It takes a steady hand and good eyesight. There’s a lot of reflection bouncing around with all that clear plastic and plexiglass,” Higgs said. “For these experiments, that work was done by my colleague Scott Huang. We use a very fine capillary tube about 3 inches long that we heat up to stretch it out to make a very, very tiny point.”

The mosquitoes were tested for the virus at multiple points from two hours to 14 days, and after 24 hours, no virus was detected in the 277 inoculated mosquitoes, he said.

INNOCULATING: Researcher Scott Huang, working in full protective gear, uses a tiny glass needle to inoculate immobilized mosquitoes with the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2 to scientifically prove that the deadly virus does not replicate in mosquitoes.

INNOCULATING: Researcher Scott Huang, working in full protective gear, uses a tiny glass needle to inoculate immobilized mosquitoes with the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2 to scientifically prove that the deadly virus does not replicate in mosquitoes.

“We used the most extreme approach, namely intrathoracic inoculation,” he said. “The hypothesis was that if the virus did not replicate in mosquitoes after that inoculation, then even if mosquitoes did feed on viremic people and the virus disseminated from the midgut, the lack of replication would preclude the possibility of biological transmission. So, we now have proof that these mosquitoes cannot spread this coronavirus.”

Higgs said it took a total of three days, working 8 hours a day to complete all the injections, and then another 3 weeks to collect and analyze all the samples. He said, like his colleagues who routinely work with infectious and sometimes deadly pathogens, the danger of infection is something ever-present.

“It’s why we have such careful controls and protocols for how things are done,” he said. “We’ve seen what these diseases can do to animals and to people. We handle them with the utmost care.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like