On the office wall behind the desk at Kriesel Certified Seed cleaning and processing facilities near Gurley, Neb., is an unassuming framed print. In the print are names of the certified seed varieties from different crops cleaned and sold by the family-owned company, going back to the 1940s.

Leon Kriesel sat behind his office desk during a recent visit to his farm, where he explained the legacy of the family business and provided a tour of their seed processing facilities on a day when they were cleaning proso millet. Kriesel and his wife, Cheryl, operate their farm and certified seed business in the state’s southern Panhandle and in the heart of proso millet production in Nebraska.

While the family-owned operation cleans and markets other seed — including wheat, oats, barley, forage seed, wildlife food and specialty grains — they also raise, condition and market certified proso millet seed. Kriesel probably knows as much about proso millet as anyone. As well he should, because his father was one of the first farmers in Nebraska to grow the crop in the 1960s. He has continued that legacy.

New variety

With the close of 2023 and the International Year of Millet, Kriesel has his sights on new markets and new opportunities for growers. “We are exporting millet into Europe, Argentina and Southeast Asia,” he says.

In the U.S., millet is mostly sold into the grain market for wild bird food, but in other parts of the world, it is a staple for human food.

A new waxy millet variety called Plateau, developed at the University of Nebraska High Plains Ag Lab about 5 miles from Kriesel’s farm, has shown potential in Panhandle trials. This variety could offer new market outlets because it is more suited to human food consumption. It has low or no amylose, which makes it sticky and more advantageous in food products, especially those that are consumed in Asia.

“This new variety, Plateau, mimics the millets from China,” Kriesel says. “We’ve shipped it over into that market, and they like it. This may be a new market for growers to stabilize proso millet production.”

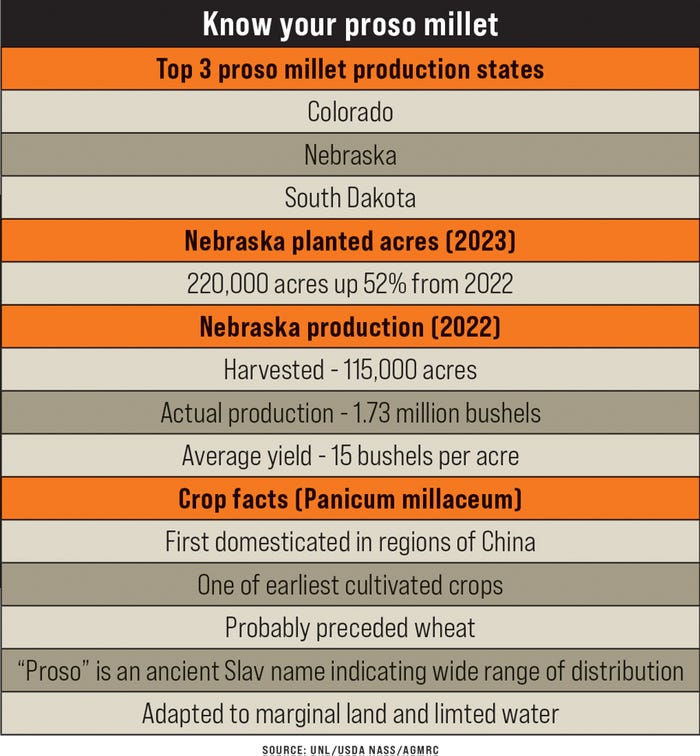

It is a cyclical, up-and-down market, to say the least. In 2022, for instance, harvested acreage in the state was 115,000 acres, down 27% from 2021, according to USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service.

Production in 2022 was 1.73 million bushels, down 55% from 2021. Turn the page into 2023, and acreage planted was at 220,000, up 52% from the previous year (see table).

Waxy millets yield about the same as other millet varieties. “Yields in 2023 were variable,” Kriesel says, “due to weather related issues. Some were in the 40- to 50-bushels-per-acre range, and some were running 20 to 30 bushels. Last year in 2022, yields were 10 to 20 bushels per acre, but that was due to the drought.”

Living the legacy

The family business started with Leon’s grandfather on his farm in Jefferson County. “He simply wanted good clean seed for himself to plant,” Kriesel says. “So, he began cleaning seed and did enough to sell to neighboring farmers. In the late 1930s, my father did the same thing, with a goal to provide customers with the best product we could at the most reasonable price we could.”

The family eventually settled in Cheyenne County and continued farming and the seed operation.

Over the years, they have worked with University of Nebraska researchers on millet variety trials. “Right now, we are working with UNL, trying to get new waxy millet into the market,” Kriesel explains.

LEGACY IN THE BUSINESS: As one of the first families in Nebraska to raise proso millet, Kriesel Certified Seed — which includes Leon (center) and Cheryl Kriesel and their full-time employee, Aaron Drinkall (right) — carries on that family legacy, growing, cleaning and marketing millet domestically and to customers around the globe, particularly in Europe, Argentina and Southeast Asia.

New millet varieties are needed. Most of the current millet varieties are more than 30 years old, he says.

“We worked closely with former UNL millet breeder David Baltensperger in the development of Plateau. He had made contact with a Japanese business that was very interested in a waxy millet while he was the millet breeder,” Kriesel notes. “Dr. Baltensperger made the first varietal crosses that included the waxy trait, and later Dipak Santra, alternative crops breeder with UNL, continued the work to get Plateau released as a variety.”

Santra is working on releasing some new varieties, possibly as early as this fall or into 2024.

Export market

“Businesses from other countries have contacted the Nebraska Crop Improvement Association, asking for the names of millet growers in Nebraska,” Kriesel says. “That direct link with our association and our business website are probably the two ways we have made contact with overseas buyers for about 20 years.

“We have a long history, so we were obvious contacts for those wanting to know more about the crop. When Plateau was released, we were contacted by some of the businesses that had inquired about millet. Many of these we now work with on an export basis, so it was a natural progression for our business to include waxy millet in our variety offerings.”

CHARACTERISTICS COUNT: While much of the proso millet marketed in the U.S., for instance, goes into wild birdseed mixtures, Kriesel says that new waxy millet varieties such as Plateau, which has characteristics that make it better suited for human food consumption, offer new markets for millet growers in places where millet is considered a food staple.

With new waxy millet varieties showing potential, Kriesel is just adding another varietal name to the long list in that framed print on the office wall of seed his family has raised and marketed over the past several decades.

Learn more at krieselcertifiedseed.com.

Swathing vs. straight cut

Millet does not dry down or ripen evenly like other crops. There is only one variety, Dawn, that dries down enough that it can be straight cut, but it is very short and early-maturing, so it is not widely grown.

“To straight cut proso millet, you would have to desiccate it five to 10 days before you can harvest it at a safe harvest moisture level of 12%,” Kriesel says. “During that time, it is vulnerable to our western Nebraska wind, so it could lodge or go flat waiting to dry down to harvest.

“In contrast, swathing when the plant is past physiological maturity allows it to finish ripening in the windrow and become dry enough for a safe harvest moisture. It is also less prone to wind damage while in the windrow.”

Read more about:

SeedAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like