June 28, 2023

Drought conditions continue to persist across Illinois, raising questions about what corn and soybean yields will look like for the 2023 growing season.

“We’re butting up against 1988 for dry weather if you look at April to June rainfall,” says Matt Montgomery, field agronomist for Pioneer. “Some of your readers will remember 1988 and the pretty tough things that came with that year. We appear to be in uncomfortable droughty territory in many areas.”

Montgomery covers the western portion of the state, and some parts of his region have received sporadic rainfall. In other areas, like west of the Illinois River or portions of the Illinois River Valley, rainfall has been sparse. “Most of that area would need a good 3 inches to break the cycle they’re in right now — which is really difficult,” Montgomery says.

Eric Snodgrass of Nutrien Ag says for the next few weeks, any substantial rain is unlikely.

“The rough news is that precipitation totals to finish June are not looking good,” Snodgrass says on June 21. “A full break in the drought is not coming in the next 10 to 20 days.”

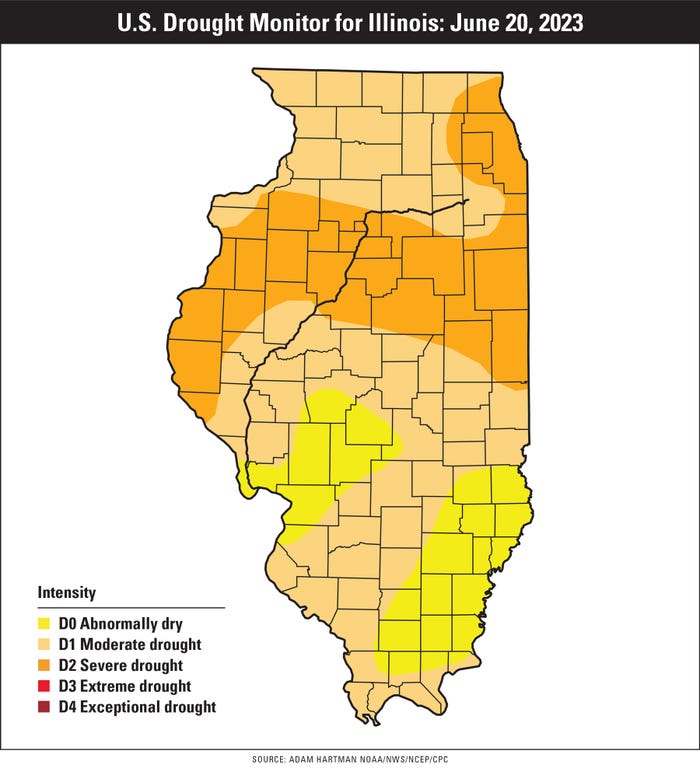

DROUGHT MONITOR: All of Illinois is experiencing drought, ranging from “abnormally dry” to “severe drought” on the U.S. Drought Monitor.

Snodgrass explains that storm complexes in the western Corn Belt and Northern Plains, with lack of a strong Bermuda high-pressure system, are robbing Illinois of moisture.

“Despite El Niño forming, a ridge in Texas, and northwest jet stream flow — the lack of high pressure over the Southeast U.S. is limiting our chances of meaningful rain,” he says. “So, it rains all around us and we continually deal with weak jet stream winds and anomalously easterly winds.”

To change this pattern, it would take something dramatic like a hurricane or tropical storm.

“Unfortunately, it takes a lot to break a drought once it becomes established in spring and summer,” Snodgrass says. “That is not to say we couldn’t see the pattern improve and more storms return, but the deficits are substantial, and Illinois would need a consistent 1.5 inches per week to prevent significant yield loss over the next six to eight weeks.”

Agronomic concerns

For the corn crop, Illinois is in a situation that needs to change soon; yield has likely already suffered. Montgomery says at 12 leaves, corn enters into the most critical stage for precipitation — some are new into that stage while others are well past it.

“After 12 leaves is when the bleed begins to start,” he explains. “That’s when you begin to rack up field losses, and that intensifies the closer you get to pollination.”

The 12-leaf stage is when water and nutrient intake increases as the plant prepares to enter into its most sensitive period of reproduction.

“If you’re just barely past 12 leaves, we’ve got reason to hold out that thin ray of hope that we’ll break the cycle just in time,” Montgomery says.

As plants approach the 12-leaf stage, Montgomery says, growers typically pull back on input investments as drought conditions persist.

Soybeans, on the other hand, are a different story.

“We really don’t know the future of the bean crop yet,” Montgomery says. “That future is told more in that late July to August period — and that’s when we need the weather to break.”

The window for soybean reproduction is spread over several weeks. If drought conditions continue into August, the soybean crop will suffer. Therefore, it makes more sense for growers to continue investing in the soybean crop further into the growing season.

Silver lining

Fortunately for the 2023 crop year, there are risk management tools and technologies available for growers that weren’t available in 1988 or even in 2012.

“It’s still depressing and frustrating, but we’re definitely in a different situation than ’88 because of crop insurance,” Montgomery says. “In 2012, people learned they had a safety net, and that softened the blow a little.”

In addition, the ag industry has made tremendous developments in drought-hardy seed genetics since 1988, and even since 2012.

And because 2012 is still fresh in some growers’ minds, they understand the risk strategies associated with weather uncertainty.

“We’ve had conversations about spreading out reproductive risk and planting corn to offset some of that sensitivity by having products silking at different times,” Montgomery says.

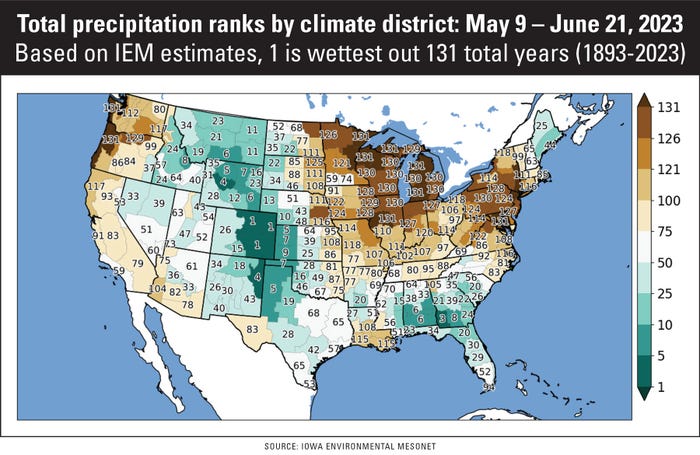

PRECIPITATION: This Iowa Environmental Mesonet map outlines 2023 precipitation from May 9 to June 21 compared to the same period over the past 131 years. The numbers represent rank where 131 is the driest and 1 is the wettest.

This is a 10-year drought, meaning a drought of this severity only happens once every 10 years or so. And the springs in between will likely still be wet.

“I would be careful not to completely scrap programs and management built around wet seasons and difficulty planting in the spring,” Montgomery says. “Because that’s probably the pattern we’re going back to at some point.”

Look for spider mites in drought

Montgomery says if drought patterns persist, growers will need to be proactive about spider mite pressure in soybeans.

“Spider mites broke out in 1988, and they broke out in 2012,” he says. “If we stay droughty, they’ll do it again.”

A field with spider mite pressure will have bronze or yellow patches, often starting on the edge of the field.

“The surefire way to know if you have spider mites is to take a white sheet of paper and to tap the plants on the paper,” Montgomery explains. “It will dislodge dirt and mites — and you’ll be able to see spider mites crawling around the paper.”

Spraying for the pest at the right time is key, following distribution in the field rather than hints of a problem.

“After you start spraying for spider mites, you’ll be spraying for spider mites for the rest of the season,” Montgomery says.

Read more about:

DroughtAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like