Flying around the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in a Chevrolet Astro van in front of 400,000 fans, Gary Marshall passed the likes of Jay Leno, Florence Henderson and Jim Nabors. In that moment, with a live audio feed back to Missouri from the Indianapolis 500, he remembered the last words of a board member before getting behind the wheel — “This damn thing had better not die.”

It was 1993, and the race pitted vehicles fueled by ethanol, propane, natural gas and electric to see which was the better bet for alternative fuels. Fortunately, Marshall’s van finished the race. Missouri was on the map as an innovator in corn ethanol use to not just motorsports fans in the stands, but also the millions tuning in on TV. And while on that day the speeds may not have rivaled the Indy cars of today, the experience was a highlight of Marshall’s 34 years as Missouri Corn Growers Association CEO.

Marshall turned over his day-to-day management of the association to Bradley Schad on March 15. Before he transitions into retirement in mid-April, he offered highlights and lowlights from his career working in the corn industry.

The upside

Missouri Corn offered Marshall several opportunities to promote the industry. Here are three of what he considers “bright spots” in his years of service:

1. Building the ethanol industry. “We started off by doing value-added, new-generation cooperatives that were farmer-owned ethanol plants here in Missouri,” he recalls. “What was actually state legislation ended up being used nationally.” Working alongside farmers to see the federal Renewable Fuel Standard come to fruition was gratifying, but not as much as the growth of the state’s ethanol industry. Today, Missouri’s corn crop is used to produce approximately 300 million gallons of ethanol and 825,000 tons of distillers grains. “Just looking here in Missouri,” he adds, “it’s been a fantastic success.”

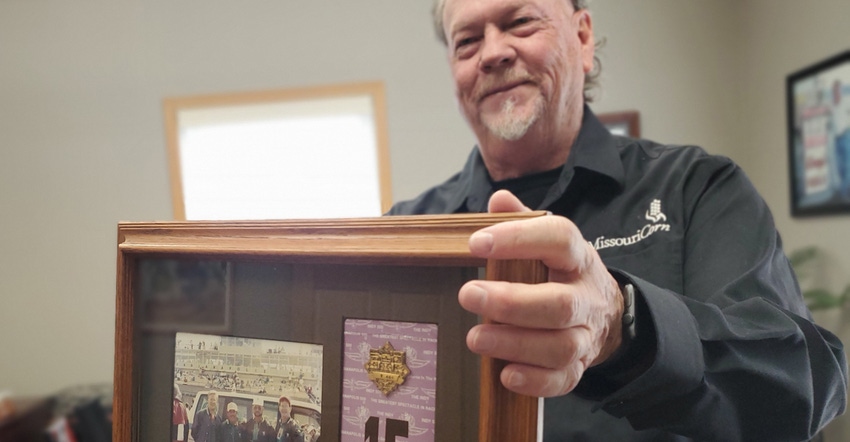

POLE POSITION: Alternative fuel vehicles took a trip around the racetrack at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway to bring awareness to advancements in technology. MCGA CEO Gary Marshall (far right) drove the ethanol-powered van.

POLE POSITION: Alternative fuel vehicles took a trip around the racetrack at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway to bring awareness to advancements in technology. MCGA CEO Gary Marshall (far right) drove the ethanol-powered van.

2. Finding corn markets abroad. A small-town boy from Jamestown, Mo., never could’ve imagined the places Missouri Corn would take him. In the last three decades, he has visited 60 countries and all 50 states. “I’ve been from one end of Canada to the other end of Mexico.” And with every trip, Marshall was looking for corn market opportunities. For years, the industry waited for export markets like China to open. “That has just blown sky-high in the last year,” he says. “It looks good for the next year or two, anyway.” Through his work, corn farmers also realized markets in Japan, Taiwan, South Korea — and the latest, in Mexico.

3. Keeping products on the farm. For the past 25 years, Marshall has been fighting to make crop protection products available for corn growers. The primary focus is on securing access to triazine herbicides for weed control with products like atrazine and simazine. “On a nationwide basis, that is a $2 billion-a-year deal for keeping the product,” he explains. “And in Missouri, it’s a $100 million-per-year savings to growers who would be faced with switching to a higher-priced product that is less effective.”

But Marshall admits not every experience has been a rosy one.

The downside

It wasn’t the daily rigors that created job frustration. Like many individuals in agriculture, it was dealing with organizations and legislation that caused the most angst.

Marshall reflects on three areas.

1. Extremists move in. The last 10 years, Marshall has seen a rise in extreme activists and activism by some of the more radical environmental organizations and anti-livestock groups like (HSUS) The Humane Society of the United States and PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals). It is not just a Missouri issue; the fight is on a nationwide basis. “It’s really disappointing to see those folks continually oppose what we do,” he says. Marshall even includes the oil industry in this category, as it pushed back on ethanol. “We’re taking some of their market, so I guess it’s easy to understand, but it’s too bad that they haven’t come more on board to help support what we’re doing for the future of our country.”

2. Backroom deals. When the Clean Air Act was written in 1990, Marshall says there was a subsection that guaranteed 25% of the gasoline sold in the U.S. must contain an oxygenate which most likely would’ve come from ethanol. Then, when it went to a conference committee, corn growers were not in the room. What came out was a change that set the ethanol industry back 15 years. “They took out ‘must have’ and inserted the word ‘should’ have.” After much work, the Renewable Fuel Standard was finalized. “We lost a lot of time there because of that simple word change; that taught me you always need to have somebody in the room whenever those negotiations are going down. And that time, the corn industry didn’t have it.”

3. Vehicles of the future. The idea for high-octane, low-carbon legislation seems like a shiny new toy, but Marshall says it’s been in the toybox for 10 years. “This is going to help to build the new cars of the future,” he adds. Electric cars have been a favorite of environmental organizations, but there is room for internal combustion engines. “We need to get that legislation on the books, because it is going to create the next generation of gasoline engines, which are going to take higher levels of ethanol — up to, like, 25% to 30%.” That is a far cry from the 10% to 15% blends today.

The memories

The success of Marshall’s time at the helm of Missouri Corn far outweighs the distractions. Still, he offers a nugget of advice: “If you only live for your successes or you only worry about the problems that are out there, then it’s a pretty tough job — or it can be. But whenever you consider all the people that you’ve met, the farmers you’ve interacted with, the places you’ve been, the hands you’ve shook, from presidents to rulers of countries — it’s the people that matter the most.”

Marshall’s career boils down to taking advantage of opportunities, like introducing ethanol by way of a Chevy Astro Van to race fans back in the 1990s. That trip around the track was a steppingstone for corn growers. Today, ethanol is a mainstay of the IndyCar Series, which uses a variation of E85, with 85% ethanol and 15% high-octane racing fuel, and it delivers an octane rating of 105.

“It has been a great career, watching all of the advancements over the years using corn,” he adds. “It’s just been a wonderful, wonderful time.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like