Have eye-popping revenue opportunities for double-crop wheat and soybeans gotten your attention yet? After all, the president himself called on U.S. farmers to double their double-crop wheat and soybean acres by 2030 to help offset Ukrainian losses and a potential global food shortage.

Even so, don’t expect Corn Belt farmers to start planting thousands of more acres of wheat this fall.

“We can do it, but it’s really quite risky, even in southern Iowa,” says Iowa State University agronomist Mark Licht, when asked if Iowa farmers planted many double-crop acres (short answer: no).

Iowa farmers prefer planting full-season soybeans, which aren’t harvested until at least October. And the earliest wheat can be harvested is late June or early July, which leaves little time for even a short-season soybean crop to mature.

“We could follow winter wheat with crimson clover, Sudan sorghum or millet, for forage, but we can’t support a large number of acres like that,” Licht says.

One challenge in Iowa is lack of market infrastructure. “It has to make sense for trucking and grain storage logistics,” he says. “We have few true markets for winter wheat or rye — mainly in south or western Iowa. They often have to truck it to Kansas or Missouri to sell it.”

Tempting revenues

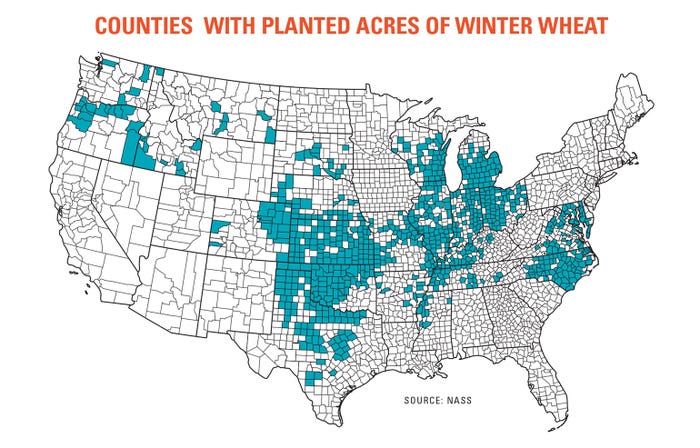

Southern farmers more commonly double-crop, as well as those in southern Indiana and Illinois, Kentucky and parts of the eastern Corn Belt. In those regions, there may be an uptick in winter wheat plantings, thanks to attractive prices.

“The opportunities for revenue in double crop are incredible,” says Purdue economist Michael Langemeier. “If your wheat stand is anything at all, there’s no doubt you’re looking at a home run.”

With Ukrainian wheat potentially reduced for at least two years, that optimism should spill into 2023.

For Indiana soils, Purdue’s first look at 2023 crop budgets shows an $830-per-acre revenue for wheat (79 bushels per acre × $10.50) plus a $542-per-acre revenue for soybeans (39 bpa × $13.90). Those are somewhat conservative figures, and your farm and marketing may achieve different results. But even after penciling in current input costs, that double-crop play would earn $123 per acre for the wheat and $263 for the soybeans in Indiana.

University of Illinois ag economists have also penciled out early ’23 crop budgets with double-crop wheat and soybeans, noting that this strategy could gross over $1,400 per acre in highly productive central Illinois soils. Returns to operator and land would pencil out to $413 per acre for wheat ($880-per-acre revenue, minus $16 for insurance and $451 for non-land costs); and $216-per-acre revenue for soybeans ($602-per-acre revenue, minus $16 for insurance and $370 per acre for non-land costs).

“Using this budget example, a central Illinois farmer could get higher operator and land return from winter wheat planted in fall 2022 plus double-crop soybeans planted in summer 2023, as compared to growing full-season soybeans or corn in 2023,” writes University of Illinois ag economist Gary Schnitkey in a recent online Farmdoc analysis.

Langemeier says he’s always surprised there isn’t more double-crop wheat and soybeans in southern Illinois and Indiana. Some farmers find it difficult to manage a summer harvest when corn or soybeans need to be sprayed.

“If you’re making $1,500 an acre, you can afford to hire someone to harvest your wheat, while you are spraying corn or soybeans,” he quips. “Maybe people don’t want to mess with wheat, but if you get one or two timely rains, the profit on double crop is usually quite good.”

Central Illinois farmer and AgMarket.Net analyst Matt Bennett agrees. “It’s crazy what some people can make planting wheat followed by beans,” he says. “You can lock in an incredible income.”

Lock in prices

Some farmers may shy away from planting wheat this fall, with the risk of a price collapse by next summer. To minimize that risk, a simple thing to do now is write a hedge-to-arrive contract for wheat for next July and for soybeans for next fall. You hedge that crop without any margin call.

“For a producer who doesn’t want a hedge account, you’ll probably pay 8 to 10 cents a bushel to the elevator to write an HTA on $10-plus wheat,” Bennett says. “So what? How many times have you been able to lock in $10-plus-per-bushel wheat when you’re planting? It’s not that often.”

You can also try options. “For soybeans, you can buy a November ’23 $13 put to set a competitive floor in place, or for those willing to take on risk, employ a strategy. For instance, a person could buy a $13 put, sell a $10 put and sell a $17 call to help finance the purchase of the $13 put,” Bennett says. “Essentially, we’re locking in $13 beans for around 15 cents-per-bushel cost. That gives some assurance that, hey, if the market gets hot and runs up to $16 per bushel, I’m still participating in that rally. Yet, you still have a strong floor underneath you.”

Or try relay intercropping

Say you really want to take advantage of high prices and get a second crop in, but the growing season makes it too risky. One way to offset that risk is with relay intercropping. You plant winter wheat or rye the previous fall, and then plant soybeans directly into that winter wheat in late April or May. The small grain gets harvested in early July and the soybeans come through that stubble and get harvested in October.

“It’s a good way to double-crop but there’s also risk there, too,” Licht says. “You have to modify the combine to add a plastic shoe that pushes soybeans down but lets the wheat heads come to the top, so you’re not cutting soybeans during wheat harvest. Some people do twin-row wheat and leave a blank space to plant soybeans.

“Relay intercropping takes a little more management to get everything done right. But if you have plenty of moisture, you can probably get 80% to 90% yield potential on wheat, and maybe 40% to 80% yield potential on soybeans, depending on moisture.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like