Mandy Bish spent the early days of fall 2023 stopping at random cornfields in central Missouri looking for tar spot, and she found it about 90% of the time.

“It might have taken me four or five plants,” the University of Missouri Extension state plant pathologist explained, “but I could confirm it pretty rapidly.”

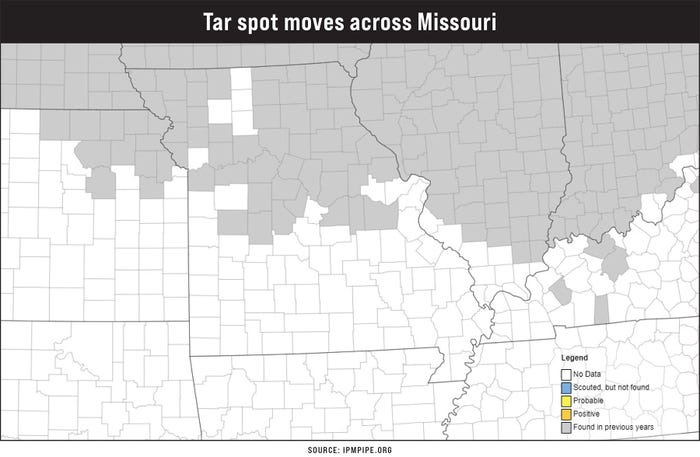

By season’s end, tar spot spread to an additional 25 additional counties in the state, bringing the grand total to 49 counties dealing with this fungal pathogen.

In most regions of the state, tar spot appeared later in the season, and yield losses were not observed. However, there were instances in northwest and northeast Missouri where yield losses occurred.

It boils down to environmental conditions and perhaps disease design.

Weather prompted early arrival

Bish’s phone started ringing in June 2023 with reports of tar spot in Missouri.

“I said it wasn’t tar spot because it was too early,” she said, “but I was wrong.”

During the MU Crop Management Conference in December, she explained how the risk of tar spot increases when cooler temperatures (minimum air temperature is less than 59.7 degrees F) and cooler dew-point temperatures (less than 55.6 degrees) combine over a window of time. And that was the scenario in the state for June when air and dew-point temperatures were about 6 degrees below the three-year average.

However, July saw warmer temperatures, with some regions reaching triple digits. “This disease does not like heat, and it got hot,” Bish said. “The disease kind of stagnated.”

By mid- to late August, cooler temperatures returned with a little moisture from Mother Nature and irrigation pivots. Tar spot started spreading once again across Missouri cornfields.

“One thing we know is you have to have some moisture for disease progression,” Bish explained. “So just seeing it first, you don't need moisture, but to have a progression of the disease, you need some moisture and that's what happened.”

With environmental conditions out of many growers’ controls, university researchers are looking into others means to slow the spread of the tar spot, right down to its DNA.

Studying the genome of tar spot

The fungal pathogen Phyllachora maydis causes tar spot. However, with the rapid spread of the disease, Bish and university researchers are wondering if the pathogen is the same in all states. Are there types (or races) of the pathogen that are more adapted to thrive in Southern climates?

University researchers are working together to answer this question. Comparing DNA from different samples of the pathogen can help scientists understand and provide researchers with more information about tar spot across the Corn Belt.

Bish said the results may provide a launching pad for opportunities to improve management of this corn disease.

Read more about:

Tar SpotAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like