It’s harvest crunch time now, so unless you’ve interseeded a cover crop at some point this summer or have already cut silage and have gotten a cover crop planted, the options for growing a good cover crop are getting slimmer by the day.

Mid-September is the typical time when cover crop plantings shift from brassicas, legumes and annual rye grasses into more cereal grains, ryes, triticale and barley.

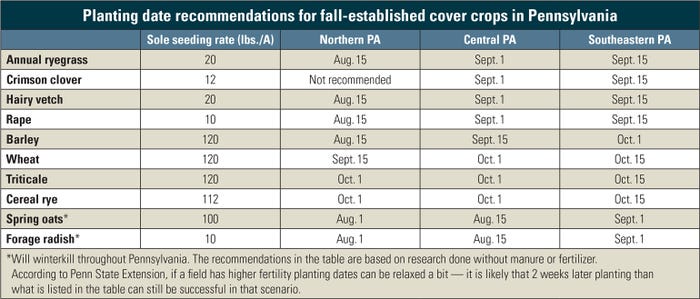

Below is a table from Penn State Extension with the most common cover crop species, their seeding rates in pounds per acre, and seeding dates based on areas of the state you’re in.

Andrew Frankenfield, Extension agronomist for Penn State, says that after Sept. 15, in most places, it is crucial to include a cereal grain in a cover crop mix.

“Be sure to include a winter cereal grain like wheat, rye, triticale or barley to any mixture to ensure good fall growth and soil protection over winter,” he says. “You can still use most of the grasses, clovers or brassicas, just mix them in.”

Scott Rushe, forage market development manager for Seedway based in State College, Pa., says the options right now are limited to triticale, cereal rye, annual ryegrass and maybe some crimson clover.

Some farmers he knows are going with a straight cereal rye or triticale this year — instead of something more expensive or even a mix — to save a few dollars because of the struggling ag economy and drought, which has affected western Pennsylvania, parts of New York and much of New England.

In New York and New England, one of the most viable options right now is cereal rye.

“This workhorse cover crop can be planted later than any other cover crop and reliably overwinters,” says Matt Ryan, associate professor of soil and crop sciences at Cornell University. “Once you get into mid- and late-September, many cover crop species are no longer an option. Some will germinate and emerge but cover crops like buckwheat, crimson clover, winter pea and forage radish will likely grow very slowly after mid-September in many parts of NYS.”

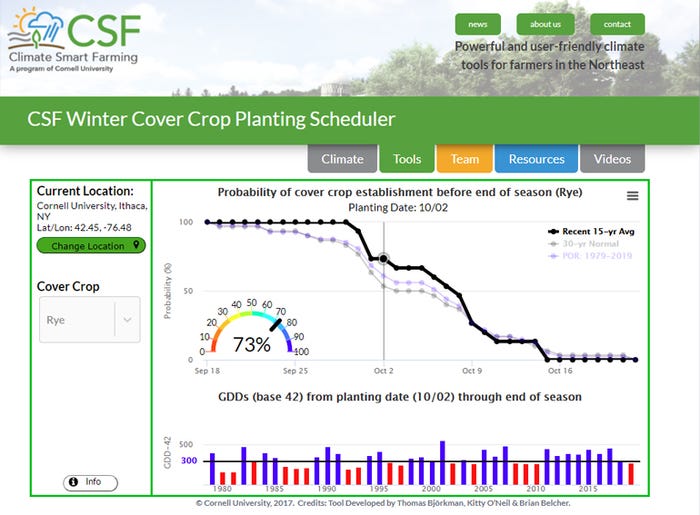

The Cornell Climate Smart Farming website has a winter cover crop scheduler that can help you determine the ideal date of planting a cover crop — limited to rye, buckwheat and mustard — in your area. Just plug in your address and it will give you a probability of cover crop establishment based on seeding date.

“The rye dates are based on getting good tillering in the fall, which is crucial when the rye is terminated soon after greenup in the spring,” says Thomas Björkman, professor of vegetable crop physiology at Cornell.

Mixing it up

The past few years have seen exotic cover crop mixes come onto the market with up to 10 different species in a mix.

Rushe thinks it’s best to keep it simple, especially if you’re new to cover crops.

“I'm more of a keep-it-basic, three, four species in a mix. Maximize the potential of each one to either … fix nitrogen, break compaction or build organic matter," he says.

An article on cover crop planting by Penn State Extension recommends grass-legume-broadleaf mixes to get the benefits of each, such as longevity of residue for the next year, nitrogen fixation, fine roots to promote soil aggregation and nutrient uptake from the cover crop. But you also want to think about the equipment your using if you’re planning to mix it up.

“A lot of these cocktail mixes have so many different seed sizes that the question becomes how do you seed it, where do you set the drill,” Rushe says. “You really need to be thinking agronomics and proper seed placement.”

Some mixes, such as cereal rye and vetch, are ideal because they complement one another, Ryan says.

“Depending on the cropping system and goals, a mixture of cereal rye and hairy vetch can be planted in mid- to late September and provide benefits,” he says. “However, hairy vetch can become a weed problem and farmers with small grains in their rotation might want to avoid planting this cover crop.

“One advantage of planting a grass-legume cover crop like this is that it can self-regulate based on soil nitrogen conditions. In low soil nitrogen, the hairy vetch will do better, whereas in high soil nitrogen conditions, the cereal rye will dominate. This self-regulation helps cycle nitrogen when it is present, avoiding denitrification and GHG (greenhouse gas) emissions, and produce nitrogen when it is lacking in the soil.”

Getting into the field

Just as planter preparations are important each spring, getting the drill ready is important in fall.

“Just like any other practice, make sure the drill is calibrated correctly for the species you're using,” Rushe says. “You want to watch the seeding depth. You don't want to seed things either … too shallow or too deep. You want to get the max seed-to-soil contact so that you get it to germinate.”

Unless you are in an area with ultra-low nitrogen conditions, applying nitrogen might not provide the benefits to justify the costs. Manure, on the other hand, can be beneficial, according to Ryan.

“In some cases, applying manure or adding mineral fertilizer prior to planting cover crops to correct deficiencies can be beneficial and save time later during a busier part of the season,” he says. “In cases where dairy manure needs to be applied due to limited storage, applying on a living cover crop such as cereal rye can help reduce runoff and nutrient losses.”

Planning for next year

Getting the most out of a cover crop largely depends on the overall cropping system, Rushe says. That means farmers should plan well ahead of time and consider what cash crops come before and after a cover crop, and what the purpose of the cover crop will be.

“You gotta plan first. The earlier you can get the cover crop in, the better, meaning you have more diversity you can use with your cover crops,” he says. “There’s no true silver bullet. Every farm needs a different mix if you will.

“It is important for farmers to think about and consider the main function that they want from their cover crop. If only one specific function is desired, then a single cover crop species might be able to better provide that function. However, if multiple functions are desired, then a multispecies cover crop mixture might have advantages.

“In addition to potentially providing a greater range of benefits, cover crop mixtures can enhance resilience and perform better across a range of environments and conditions. Including different plant families (e.g., grass and legume, etc.) and considering the different traits and functions they might provide is important when selecting species to include in a mixture.

“Start small, don't go total acreage. See what the cover crop will do for you and adjust accordingly.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like