Since its 2015 debut in the U.S., the fungal corn infection tar spot has challenged researchers with quirks that make it just a little bit different than the tar spot Latin American countries have dealt with for decades. For one, it caused yield losses in 2018 at half strength.

Only one pathogen has been tied to tar spot in the north. In its southern reaches in Latin America, that pathogen collects in “tar spots” on leaves, and a second joins the mix to create fisheye lesions. Without the second pathogen, research from the south holds that farmers won’t have fisheye lesions or a yield impact.

Yet in Illinois, it’s estimated that tar spot took 10 to 20 bushels per acre where the disease was most severe. Some samples sent to the University of Illinois plant pathology lab also show fisheye lesions where only one pathogen is present.

“The idea that fisheye equals yield loss, no fisheye equals no yield loss — we’re questioning that in the north,” says Diane Plewa, a graduate student and plant pathology lab employee.

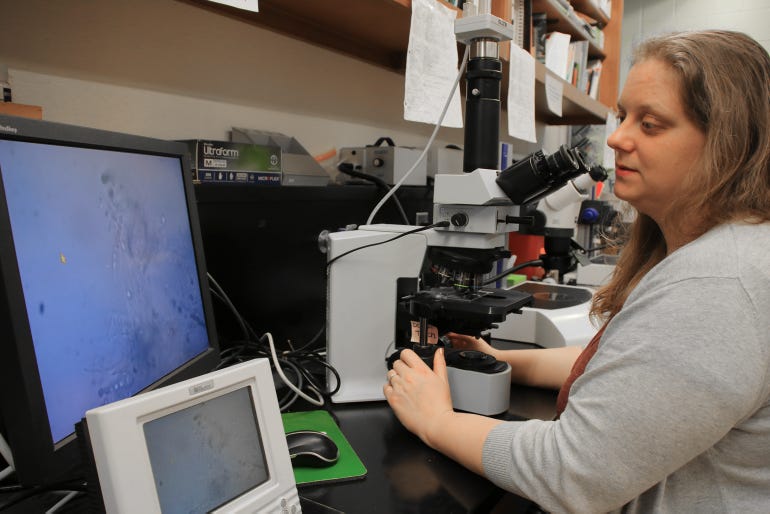

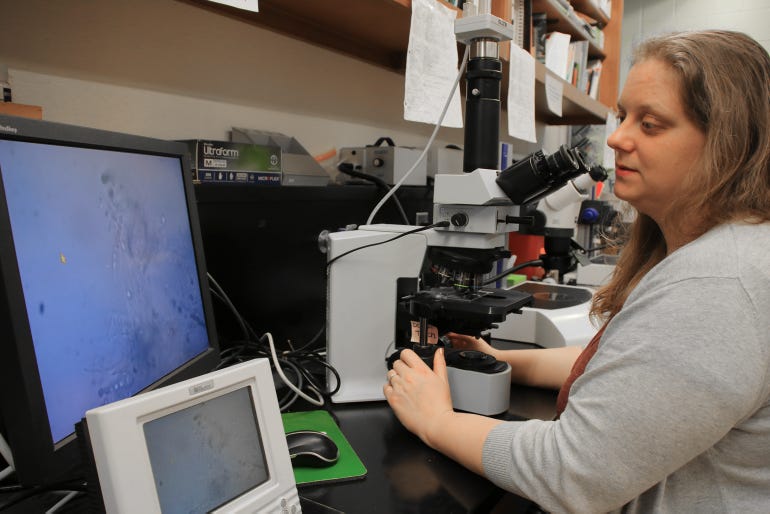

Plewa works with U of I plant pathologist Nathan Kleczewski to screen samples of tar spot sent in from across Illinois, as well as from other infected states such as Wisconsin, Indiana and Iowa. They’re culturing fungi from fisheye lesions and trying to isolate genetic differences between different sources of the pathogen present in the north.

MICROSCOPIC: Diane Plewa inspects a sample of tar spot under a microscope.

Kleczewski says little is known of tar spot’s regional impact, as 2018 was the first year it “blew up” in Illinois. He says cool and humid conditions in the northern part of Illinois in July were ideal for the pathogen.

So long as the weather conditions were primed, tar spot often caused yield losses in spots where it had been just a nuisance before — though Kleczewski says it’s unclear how much yield loss can be attributed to tar spot as opposed to other diseases present in a field.

“A lot of our fungi like wet conditions, right? So this year, we had tar spot that was an issue in many places, but there were also other diseases that came in and caused damage to crops, such as gray leaf spot or some of the ear rots,” he says, adding the combined effects of multiple diseases likely added up to more yield loss.

Nick Hustedde, an agronomist with FMC Ag Solutions, adds that the heaviest infections in 2018 caused rapid early drydown in northern Illinois fields, sometimes occurring within 14 days after infection. Carbohydrate scavenging during this period greatly reduces standability, which further impacts yield.

“Either the Phyllachora organism of tar spot by itself is capable of causing these issues in our climate, or you’re seeing a complex occur between tar spot and gray leaf spot or other foliar pathogens,” Hustedde says. “That’s still being investigated.”

Managing tar spot: Hybrids and spraying

Golden Harvest agronomist Stephanie Porter says Syngenta has had a management plan in place for tar spot since the fall — in time for farmers to make hybrid selections for 2019 with a new disease rating scale that includes tar spot.

“Before 2018, people would always equate tar spot to soybean rust, where they thought soybean rust is going to be horrible, but it would only ever come really late in the season in Illinois, and maybe be in few fields,” Porter says. “People thought tar spot would likewise never come in as aggressively. That turned out to be wrong this year.”

It could be years before conditions align for another outbreak in Illinois, she says, adding farmers should have a management plan involving fungicide to fall back on if weather conditions look conducive.

Kleczewski says hybrid selection is a limited solution for growers at the moment. In a trial of Illinois commercial varieties, he found no particular brand had hybrids that were more resistant than other brands.

“Most of our hybrids are really susceptible, but there are a handful that appear to be more tolerant than others. It could be that those companies were selecting for some other trait, and they just happened to pull in some characteristics that made corn more tolerant, as well,” Kleczewski says.

He says his results largely echo another trial for tar spot susceptibility conducted by the University of Wisconsin. In it, companies including Burrus Seed had high-rated hybrids along with lower-performing hybrids, though Burrus is waiting until after the next growing season to release a rating scale on its seeds, says Chris Brown, Burrus field agronomist.

He says he’s worked with growers to plan effective fungicide control for Burrus hybrids.

“I tell growers to keep an eye out for those moderate temperatures, 65 to 75 degrees [F], combined with periods of wet, moist conditions that are most advantageous for the disease. Under these conditions, you will want to consider a pre-emptive fungicide treatment before you even find tar spot,” Brown says.

Porter says Syngenta has done work in Latin America that it’s used to help inform U.S. management plans. The company has recommendations of fungicide programs with several different products and modes of action.

“You want to spray around tassel or R1. In parts of other countries, if it comes in earlier, let’s say in Latin America, they also would recommend a V4 to V8 spray. I try not to push a second spray here,” she says, concluding it wouldn’t pay off for farmers. “I’m not going to tell the farmer to do something if he’s not going to make money.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like