With rain delays and a slow start for harvest this fall, a number of cornfields in Iowa developed ear rots and kernel molds. In addition to too much rain, moderately warm temperatures encouraged mold growth. Also, while waiting to be harvested, many soybean fields developed quality problems.

“It’s important to scout each cornfield and identify ear molds that may be present prior to harvesting the field,” advises Alison Robertson, Iowa State University Extension plant pathologist. “Proper identification of ear molds can help determine grain handling risks and help you develop a plan to limit the impact of the mold on other grain. You want to isolate the grain that has the mold, so it doesn’t contaminate other grain in storage.”

Consult your grain merchandiser to find marketing opportunities for moldy grain, and limit the amount of time it is kept in storage.

What can you do about mold on corn?

“Before harvesting these fields, it’s important to first look at some ears in various locations in each field,” says Robertson. “Identify what kind of mold is out there, if any, to help you determine if there may be a toxin problem.”

Some types of ear molds have the potential to produce mycotoxins. These compounds can have detrimental effects to both humans and livestock if present in food or feed. Field molds normally don’t grow on corn kernels during storage after corn is dried down to safe moisture content. But holding wet corn in bins and slow drying of the grain in bins can cause mold growth and allow toxins to increase before the corn is dry.

Charlie Hurburgh, ISU Extension grain quality specialist and director of the ISU Grain Quality Testing Lab, says, “I can’t emphasize enough: Farmers need to avoid holding wet grain in bins or wagons for very long. Dry it down to safe moisture content, and do it quickly.”

Properly identify molds, mycotoxins

ISU specialists helped develop YouTube videos on ear rots and mycotoxins in corn. And a mycotoxins app is also available for both Android and iOS as a guide for navigating the sometimes-confusing world of grain quality issues. The Corn Mycotoxin App is available for free at app stores and has information on corn ear rot pathogens that cause yield loss and quality issues.

The app also provides instructions and information for corn farmers and livestock producers for a proper management plan for corn infected with mycotoxin. It has information about the symptoms and mycotoxins produced by predominant corn ear rot pathogens, the toxic effects of mycotoxins on humans and livestock, and safety levels for different uses of infected grain. The app offers tips on storing moldy grain, ear rot management before and during harvest, and testing corn for mycotoxins.

Cool stored corn to 40 degrees F or below

No matter if your corn has mold or not, Hurburgh says the two most important steps this fall are: dry corn quickly and avoid long wet corn-holding periods; and cool the corn as quickly as possible once it’s in a storage bin, after drying it to safe moisture content.

If you can’t dry corn as soon as you harvest it, in either a continuous flow dryer or an air-flow drying bin, the grain won’t keep very well, especially in wet weather. “The key is to get that corn into the bin at a cold temperature,” says Hurburgh. “When the outside air temperature or dew point is 40 degrees [F] or below, every fan in Iowa should be turned on and running, to get as much of this grain as cold as we can as soon as possible.”

What’s the ideal temperature to cool stored corn? “We like to get the grain below 40 degrees [F],” he says. “It depends on the dew point. The weather was warm and wet into mid-October — warm for that time of year. And those are conditions that generally produce mold on ears in the field, and the toxin issue.”

Grain buyers are looking for toxins

Grain elevators are looking closely at corn samples pulled from loads coming in this fall. Some are running a black-light test. A blue-green glow from corn under a black light is somewhat correlated with the presence of aflatoxin. “I don’t think we’ll have many aflatoxin problems this fall, so the black-light test probably won’t show us much,” says Hurburgh. “While the glow under a black light can be an indication of aflatoxin, it’s not highly correlated. At least it gives you an idea of whether the risk of aflatoxin is there.”

What about vomitoxin? Hurburgh thinks this toxin will present the most problems with this fall’s corn harvest. “For detecting vomitoxin, a black-light test doesn’t do anything,” he says. So how do you determine whether corn has a risk of producing vomitoxin? The only way is to conduct a strip test on a corn sample. “A grain buyer could do this twice a day, to determine if corn in the area might have a vomitoxin problem,” notes Hurburgh. “Some grain elevators are doing this testing.”

MORE MOLD: With an unusually wet start for harvest this fall, fields developed a higher incidence of mold growth on corn ears. This is the Gibberella fungus.

There’s no rapid way to tell if corn will produce mycotoxin. “If you see mold that looks like a white sheath growing on corn kernels on an ear, if it is white from the tip of the ear on down, that’s the Gibberella fungus that can produce vomitoxin. That’s the clue indicating maybe this corn should be tested with a strip test. If you are feeding your own corn to livestock, get it tested,” advises Hurburgh.

Ethanol plants concerned about vomitoxin

Why are ethanol plants worried about vomitoxin possibly being in corn they receive? In Iowa, a large amount of dried distillers grain produced by ethanol plants is fed to pigs, and pigs have the lowest tolerance for vomitoxin compared to cattle or other livestock. Pigs are most sensitive to vomitoxin. An ethanol plant fermenting corn and processing it to make ethanol will concentrate, by a factor of 3, anything other than starch that comes in with the corn. If toxin comes in with corn to the ethanol plant, it comes out of the ethanol plant with three times as much toxin in the DDG.

“If you start at 1 part per million vomitoxin in corn, the DDGs produced will be 3 parts per million. That’s why ethanol plants are concerned,” says Hurburgh. “They have a 3-to-1 concentration factor. If you are feeding corn that came from the same area that produced corn for the ethanol plant, you could have two sources of vomitoxin in the same hog ration: corn and distillers grain.”

Dry corn quickly, then cool it to keep it

Summing up, the best way to handle the challenges of this fall’s harvest is, don’t hold wet corn; get it dried down right away. If you can’t do that, then run cold air on it and cool it down as fast as possible. Controlling grain temperature is the fastest way to slow down mold growth in grain.

Drying corn as quickly as possible means running grain bin dryers at their maximum temperature. “And using a continuous-flow, high-temperature dryer is even better, because they dry faster than bin drying systems,” notes Hurburgh.

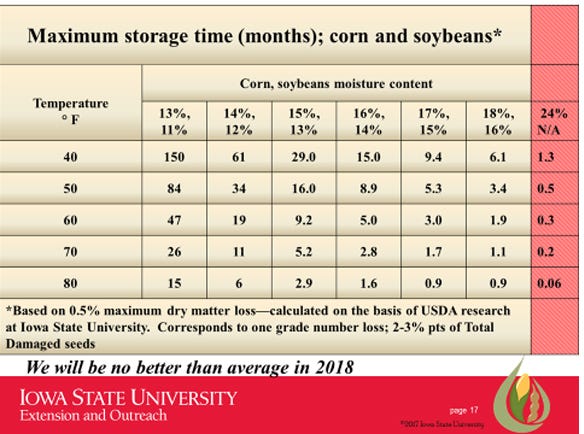

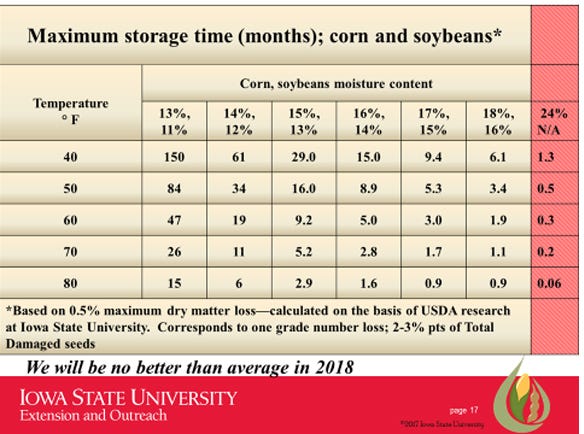

The table below shows the time, moisture and temperature relationship for safe storage. These recommendations are for sound, good-quality grain; storage times for poor-quality or damaged grain should be reduced by about half. Example: 18% moisture corn that has a high incidence of field mold would have a storage life of only 1.7 months at 50 degrees F, compared to sound, high-quality, 18% moisture corn, which could be stored at the same temperature for about three-and-a-half months. Mold and mycotoxin issues tend to be worse on broken and damaged kernels and fines relative to sound, whole kernels.

Both temperature and moisture content are important in grain preservation, but often temperature control is the most immediately important if drying capacity is limited.

Crop insurance eligibility

Farmers may be eligible for a crop insurance quality adjustment payment if their soybeans or corn were significantly damaged by wet weather this fall. Harvest delays due to heavy rains resulted in increased instances of field loss, abnormally high harvest moisture content, and mold growth on corn kernels and soybeans.

To be eligible for payment, soybeans must grade “sample grade” or worse, with total damage (by U.S. grade) exceeding 8%, according to USDA’s Risk Management Agency. For corn, it’s 10%. Growers should have filed a notice of loss with their insurance agent within 72 hours of discovering the damage and the adjuster having gathered samples in the field or in your bins.

Keep good harvest records. Use “soft records” for your first report: yield monitor data (with calibration) or weigh wagons; or use scales on grain carts, scale tickets and self-measurement of grain bins. If a crop insurance loss occurs, then “hard records” such as official grain bin measurements, warehouse receipts or settlement sheets are required.

Farmers anticipating delivering significant amounts of wet or damaged soybeans should work with their soybean merchandiser on specifics of their dried-weight calculations and damage discounts. Some elevators and processors have adjusted their grain receiving policies and/or discount schedules due to poor-quality beans.

Farmers selling weather-damaged corn or soybeans may still qualify for Market Facilitation Program (MFP) payments. “Quality of the crop harvested is not taken into account,” says a USDA announcement. “MFP payments will only be made on units harvested, regardless of whether they’re sold or stored.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like