Greg Anderson was disheartened when the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency announced 2023-25 biofuel blending volumes in June. The Newman Grove, Neb., farmer described the lower-than-expected volumes as a “gut punch to rural America.”

That’s because for the past year or so, both oil and ag processing companies had been trumpeting big expansion plans leading to a boom for U.S. renewable diesel, thanks to friendly government policies that promote green energy. Now that rosy future is in doubt.

Anderson has a good idea of how far-reaching the ripple effects will be after EPA decided to increase biomass-based diesel production only slightly between 2023 and 2025.

“It’s a big letdown for farmers, American energy security and economic growth in rural America because the biofuels industry creates thousands of sustainable job opportunities,” he says.

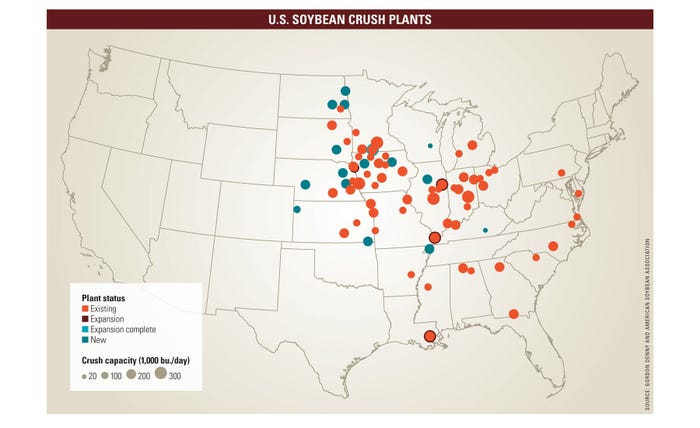

The issue hits close to home for Anderson. Two crush plants are being expanded within 60 miles of his farm in northeast Nebraska, which will have the ability to consume 25% of the Husker State’s soybeans by 2025. “That means stronger basis, more demand, good-paying jobs and economic stability,” he says.

“The more you can keep those dollars turning over at home, the more you can increase the value returned to rural communities,” touts Anderson, who also serves as a board member for Clean Fuels Alliance America.

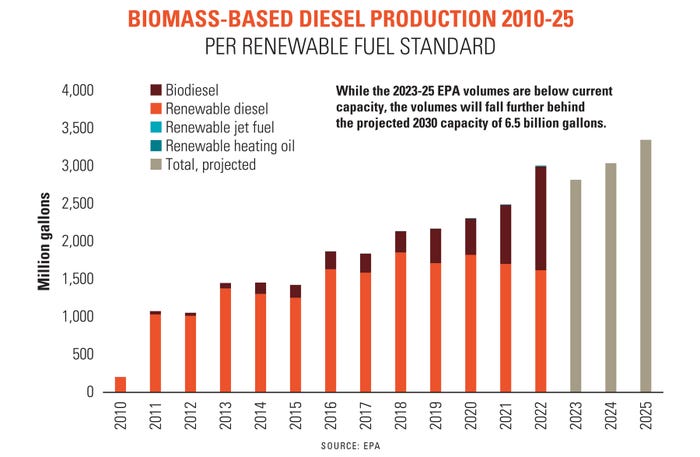

The biomass-based diesel volumes directed by EPA in June will increase mandated volumes for biomass-based diesel production (including renewable diesel) by 19% over the next two years. Production volumes in gallons were set at:

2.82 billion for 2023

3.04 billion for 2024

3.35 billion for 2025

The growing volumes will rely heavily on oilseed, fat and grease feedstocks to fuel that growth, which has in turn stimulated oilseed market prices higher over the past couple years.

So what’s the problem? EPA data finds that U.S. biobased diesel production already topped 3 billion gallons — in 2022.

“The industry is on track to produce volumes over the 2025 levels already this year,” says Scott Gerlt, chief economist at the American Soybean Association. That means that the recently announced EPA volumes are not high enough to support the surge in soybean crush plant expansion and new-build announcements made in the media over the past few years.

“We’re trying to figure out what’s going to happen and see how this is all going to play out,” says Mike Steenhoek, the executive director at the Soy Transportation Coalition. “These are expensive projects, and it’s hard to project demand. You can’t overproduce.”

The impending boom

According to EPA, biobased diesel production — which includes biodiesel, renewable diesel, renewable jet fuel and renewable heating oil capacity — surged 21% in 2022, as consumers and companies alike pushed for new options to reduce reliance on carbon-intensive fuel sources. And the pace isn’t going to slow down anytime soon.

“It’s coming from customers and coming from boardrooms,” Steenhoek says. “We expect we will continue to see that movement in this direction.”

The push for more green energy is good news for farmers across the U.S. — in theory. Renewable diesel is the biofuel industry’s rising star after output nearly doubled between 2021 and 2022 to 1.4 billion gallons. A September CoBank report estimates that recent company announcements regarding crush plant expansion and new builds would put 6.5 billion gallons of renewable diesel production on line by 2030.

But “the renewable diesel expansion isn’t as much of an ‘If you build it, they will come’ scenario as the pandemic-era expansion announcements made it out to seem,” observes Joshua Baethge, Farm Futures policy editor.

Biodiesel and renewable diesel production is still not profitable without government programs, says Joanna Hitchner, acting oilseeds chair at USDA’s Interagency Commodity Estimates Committees for the World Ag Outlook Board, which publishes the World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE) reports.

That means government mandates are necessary to incentivize private expansion at soy crush plants across the country. “The price of biodiesel is above the price of diesel, so you need a mandate to make renewable diesel work,” Hitchner explains.

“Demand is driven by the mandate,” she says in regards to soy oil usage estimates for biobased diesel production in the WASDE report. “Our assumption is that the biofuel blending volumes are binding. That is the demand driver.”

Ethanol overlap?

If it sounds similar to the ethanol boom of the early 2000s, that’s because it is, says Ken Zuckerberg, lead industry analyst for biofuels at CoBank. “Ethanol paved the way, and now renewable diesel is the next chapter in the biofuels evolution.”

The threat of overproduction looms large for the burgeoning renewable diesel industry. “I worry about creating overcapacity,” he says. “As ethanol production ramped up, overcapacity eventually came into play.”

Hitchner agrees. “Once you overbuild capacity and exceed the mandate, it disincentivizes production,” she says.

“The EPA can squeeze the economics of renewable diesel without feasible blending volumes,” Zuckerberg says. “For this to be profitable, the renewable identification number [RIN] values coming from the market need to come down.”

RINs are essentially the currency for the Renewable Fuel Standard program. Producers create RINs when they make biofuel, and oil companies retire RINs for compliance when they blend the purchased biofuel into petroleum.

Unlikely allies in trenches

A benefit of the push for renewable diesel is that Big Oil is no longer fighting EPA on RIN oversight, as it persistently has with ethanol. That’s because the renewable diesel production process allows companies like Phillips 66, Marathon, Chevron and Valero to generate their own RINs instead of purchasing them.

“Renewable diesel production uses the same operations in the refineries,” Gerlt says. “It’s a straightforward process that allows Big Oil companies to capitalize on producing a lower carbon-intensity fuel while still using their current facilities.”

But the shortfall in EPA capacities announced in June increases the likelihood for overcapacity, Gerlt forecasts. “There’s billions of gallons of capacity that won’t come to fruition because companies are not going to produce over the blending levels,” he says.

Indeed, Cargill axed plans to build a new soy crush facility in Missouri in early June amid “shifting market dynamics.” Exxon Mobil also threw in the towel on an earlier deal to purchase green fuel additives from Global Clean Energy Holdings after its expansion plans were delayed due to a lack of skilled labor.

“The slowing construction paces right now are mitigating that concern,” Zuckerberg says. “We are expecting building delays over the next two years because of rising interest rates, high construction costs and labor shortages.”

Gerlt and Zuckerberg expect plants that have already broken ground on expansion and new build projects will likely plow forward with construction. But it will be more difficult for smaller companies to wait for EPA to someday increase volumes.

“These plants can come on line and underutilize their capacity,” Gerlt says. “But we have the ability for billions of gallons to be under capacity.”

Surplus opportunities

That is a tough pill for consumers and farmers alike to swallow. Anderson notes that renewable diesel and biodiesel already makes up 46% of California’s diesel pool, up from 33% in 2021. And in Northeastern states, he says biodiesel is being mixed into heating oil to decarbonize it at a faster pace than regulators had originally intended.

“Renewable diesel is a cousin of biodiesel but has a key benefit,” Zuckerberg says. “It does not need to be blended with traditional diesel.”

That means by using renewable diesel and biodiesel, automakers do not need to modify engines to reduce carbon emissions — a rare mutual benefit for Big Oil, Big Ag, Big Auto and consumers alike.

“We have people knocking on our doors asking for the product,” Anderson says. “There is a lot of interest from railroads and in states where they are eager to increase consumption of lower carbon-intensity fuels.”

Ripple effect

As soymeal volumes increase with rising soy oil demand for renewable diesel, opportunities also grow for other producers, outside of soybean farmers. “That makes feed cheaper for livestock and poultry producers,” Anderson says.

That would make U.S. meat more affordable and increase international demand for domestically produced meat products, adding even more value to livestock and poultry operations. Steenhoek summarized the potential added value this way: “It is more profitable to export meat than meal and meal than beans.”

It would also improve U.S. competitiveness in soymeal globally at a time when Brazil has cornered the market on whole soybean exports throughout an entire year — not just at fall harvest.

“There are plenty of other countries that still have strong meat demand that currently lack the processing capacity for feed,” Steenhoek says. “Supply chains love consistent volumes and timing. Plus, the more you can diversify your supply chain, the more resilient you are as an industry.”

Some infrastructure issues would need to be addressed before reaching that point, he adds. Soybean meal can cake, which makes it more challenging to move through port terminals. “We’ve been exporting meal for years, so it’s not a new problem. But if volumes increase, these ports need the infrastructure to handle those volumes in a timely manner.”

That could include building more storage facilities and expanding rail unloading capacity at ports to handle higher soymeal volumes. More loading terminals at ports would also improve shipping speeds.

If the soymeal surplus stimulates overseas meat sales, then additional refrigerated container and storage capacity may also need to be built.

“There needs to be a lot of consideration put into these expansion plans,” Steenhoek says.

How to feed the beast

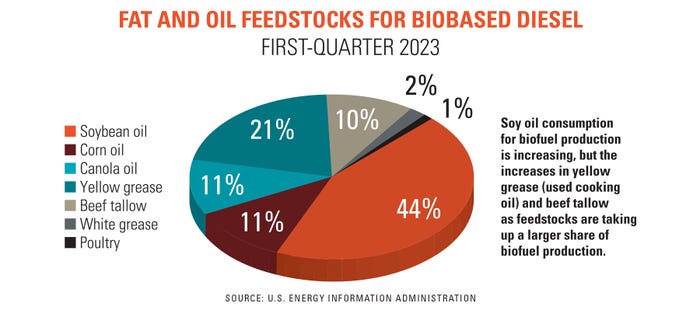

Closer to home, farmers are grappling with their abilities to provide adequate feedstocks for the anticipated renewable diesel expansion. Tanner Ehmke, CoBank’s lead grain and oilseed economist, has watched the market entice other feedstocks, like canola oil, sunflower oil, used cooking oil and beef tallow, to name a few, into these plants.

“Soy oil priced itself out, so the other sources are finding their way into the feedstocks fold,” Ehmke reports, as cooking oil begins to steal the total feedstocks share from soy oil. “Other sources are finding their way into the supply chain, which has dampened the demand for soy oil.”

“A couple of years ago, soy oil was 55% of feedstock use for biodiesel and renewable diesel,” Hitchner says. “It has drifted lower because of alternative feedstocks and lower carbon-intense feedstocks incentives in California.”

The growth in renewable diesel production has attracted more canola oil from Canada, especially after EPA approved the pathway for canola oil into renewable diesel in December. Hitchner cites the increased availability of other imported feedstocks, like tallow, as driving down the share of soy oil used for renewable diesel feedstocks this year.

But if consumer demand for renewable diesel can keep production prospects more profitable than EPA has allotted, farmers could be incentivized to grow more soybeans in upcoming growing seasons.

“Moving forward, there are partnerships between renewable diesel and soy processors so that soy oil can increase its share,” Hitchner notes.

The million-dollar acreage question

Could that pull more oilseed crops — like sunflower and canola — into production? “It will be driven by the mandate,” Hitchner forecasts. “It would be more around the fringes of acreage expansion and not likely to a great extent.”

In Nebraska, Anderson does not plan to change production and doesn’t think EPA’s decision will change other farmers’ planting intentions either. “They’ll take in a host of other factors for 2024,” he says. “The EPA’s decision doesn’t lessen the demand we are seeing for soy oil to go into renewable diesel.”

Hitchner does not expect to see more than a 50-50 split for corn and soybean acreage. The second year of a soybean-on-soybean rotation notoriously raises the risk for lower yields. Anderson has mastered continuous soybean rotations but cautions that the ability to do so requires drastically different management strategies than corn-soybean rotations.

“Nutrient needs vary,” he says. “It depends on location and starts with the soil.”

He recognizes corn and soybean acreages are largely maxed out in the U.S. and agrees with ag economists that U.S. soybean export volumes will likely shrink as more domestic usage goes toward renewable diesel production.

Many economists expected an increase in soybean acres this year, but USDA estimates 87.5 million acres of soybeans will be planted for this year’s crop — only a 0.1% increase from 2022.

“It didn’t pan out, because Ukraine and Russia changed the dynamic a fair amount,” Ehmke says. “Grain prices spiked and that pulled more acres into cereal crops. If it weren’t for Ukraine and Russia, farmers would’ve otherwise prepared for the pending demand increase in vegetable oils.”

“We don’t foresee a lot of acreage growth because of this industry expansion. We expect that more soybeans will be pulled out of U.S. exports,” Hitchner says, noting that if an acreage expansion does happen as a result, it will likely be in Brazil where it is less difficult to buy acreage than in the U.S.

As long as Brazil is producing record soybean crops, the need for the U.S. to be a major exporter is diminishing.

“We are experiencing a transition in which the U.S. is going to be more focused on domestic use, and pricing will follow those usage trends,” Ehmke says.

Tight U.S. soybean stocks, he adds, will keep the U.S. less competitive against Brazilian exports and more reliant on domestic soy usage and alternative feedstocks

to maintain renewable diesel production.

Read more about:

Renewable EnergyAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like