USDA reports always provide answers. But the agency’s Sept. 12 production estimates likely raised even more questions for traders to ponder heading into an uncertain harvest.

Both yields and acreage fell, reducing the size of U.S. corn and soybean crops fell much more than expected. Corn lost 2.9% of its output, with 1 million less harvested acres and yields off 2.9 bushels per acre to 172.5 bpa. At just under 14 billion bushels the crop would be the smallest since 2019.

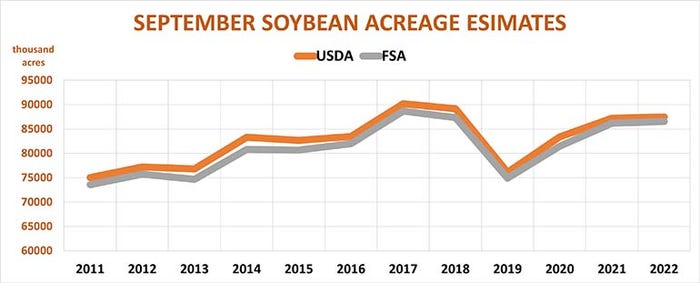

The changes to soybeans were even more dramatic. The government’s estimate of total production fell 3.4%, thanks to 600,000 fewer harvested acres and yields that tumbled 1.4 bpa to 50.5 bpa. At 4.378 billion bushels, output would be the smallest since 2020.

USDA’s corn yield estimate was right on track with what most models predicted. That was the only number that wasn’t a surprise, if not an outright shock. The soybean estimate went contrary to most models, which suggested August rains stabilized, and maybe even improved yields.

Bean yields may not be the only estimate to watch for changes in coming months. But different data collection methods complicate using historical comparisons to guess what those revisions might be.

FSA vs. NASS

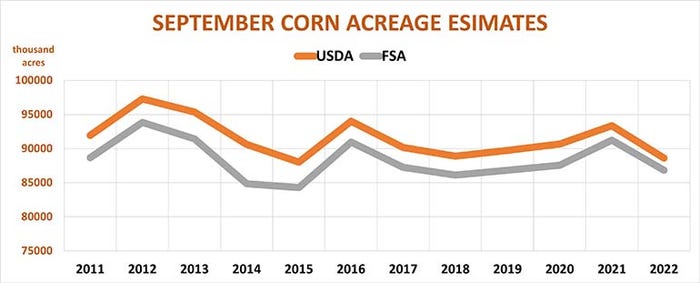

Some cut in acres was expected headed into the report, after the agency’s National Agricultural Statics Service issued a last-minute notice it would update the data due to early collection of farmer planting reports filed with the Farm Service Agency. Normally the larger FSA sample wouldn’t be folded into the NASS sausage-making of estimates until October.

The August FSA data suggested modest cuts were likely but nothing near the print after a resurvey of late-planted states released in August.

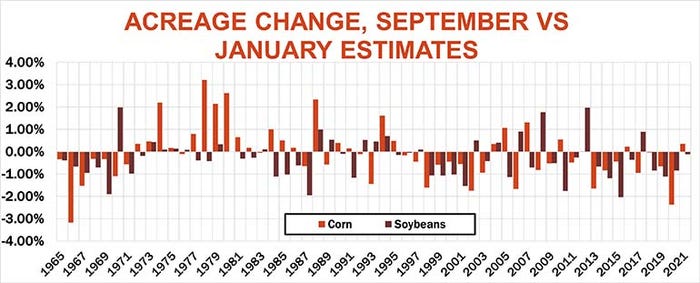

How unusual is it for USDA to change acreage in September? Since 1965 USDA changed its corn harvested acreage number about one in every three years from August to September, most of the time cutting the estimate. Soybean changes happened only one in five years, with reductions in all but one of those years.

The September acreage update clouds forecasts based on USDA’s published track record. In the past USDA showed a tendency to cut harvested corn acres from its September report to the last monthly estimates put out in January. But in years when the September estimate fell from August, like it did in 2022, the January release tended to be higher, with the difference great enough to be statistically significant. If this connection holds true, January’s corn number could be back up to the 81.8 million figure from August.

USDA’s September soybean acreage estimate has a better chance of holding. The official reading on harvested ground tends to fall from September to January, and that’s also true of years when September was lower than August. So, while USDA’s yield estimate looks shaky, any increase could also be offset by another cut in harvested acreage.

Export logjam breaks

Production wasn’t the only area with data questions following break-down last month of a new computer system for collecting sales reports filed by exporters. Four weeks later the agency finally figured it out. There’s typically variances between estimates from different wings of the government’s data machinery. The weekly corn export data published by the Foreign Agricultural Service was 150 million lower for the 2021 crop year that ended Aug. 31, while the soybean total was around 45 million lower than the Sept. 12 World Agricultural Supply And Demand Estimates.

USDA updates Sept. 1 inventories in its quarterly grain stocks dump at the end of the month, so beginning supplies available at the start of the 2022-2023 marketing year could be adjusted as well. Ethanol demand looks a little better than USDA’s current tally, but soybean crush should be in line with previous estimates based on August usage by members of the National Oilseed Processors Association.

And so-called residual usage numbers could change if USDA modifies its 2021 crop production forecasts.

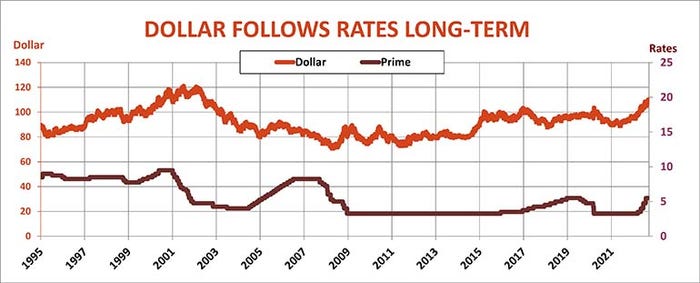

Turbulence in financial markets that slammed futures across the board complicates attempts to forecast 2022 crop demand. Another hot inflation reading in the U.S. triggered a selloff on Wall Street, prompting fears the Federal Reserve could raise interest rates another three-quarters of 1% at the end of its two-day meeting Sept. 21, and signal more severe tightening ahead to stem rising prices. That prospect increased fears that the move could prompt a recession in the U.S. just as other global economies face even worse prospects.

The flight to safety and higher U.S. Treasury yields sent the dollar back to 20-year highs. While that doesn’t impact U.S. grain exports directly, lack of foreign currency reserves, especially in emerging market countries, mean many customers may have less to spend on food imports even as prices remain near all-time highs.

No China rescue?

The government lowered its forecast for 2022 crop demand due to smaller supplies, and usage may be even more bearish than that outlook. Exports ultimately will depend on whether foreign competitors have much to sell – another big unknown with the war in Ukraine dragging on and La Nina threatening production in Argentina.

China also remains a huge question mark ahead of the Communist Party Congress next month that is expected to solidify the grip of President Xi Jinping at the helm of the world’s largest soybean importer. USDA’s Ag Attache in Beijing lowered its forecasts for the country’s soybean imports, which fell 12% last year according to recent China customs data. “China’s slowing economy and COVID-related restrictions continue to weaken demand for oilseeds for feed and food use,” the report noted.

China isn’t likely to come to the rescue of U.S. corn growers, either. Increasingly close ties to Russia are one constraint. The government there has also completely abandoned any pretext for boosting ethanol blending in gasoline to reduce pollution. USDA forecast China corn imports will fall 22% year-on-year after tumbling the much in 2021-2022 from the all-time high reached in the 2020 marketing year. As seems to happen every decade or so, hopes for a China corn import renaissance once again have crashed and burned.

Price targets, fertilizer

So where does that leave hopes for a rally? While I’m not as bullish as USDA’s WASDE forecast, my pricing models are still optimistic. Average nearby corn futures for the 2022-2023 marketing year are put at $6.35, with the selling targets from $7.35 to $8.35. December corn failed at a test of $7 last week in the wake of WASDE, but remains in an uptrend off July lows.

November soybeans, meanwhile, couldn’t hold a quick probe over $15 post-WASDE, close to my average nearby futures forecast of $15.05 for the crop. The potential selling range of $16.30 to $17.55 remains far off above contract highs, waiting for confirmation of lower production and problems in South America. Answers on those questions are still likely months away, leaving the market to wait for harvest lows.

Fertilizer prices reflect all these concerns. Nitrogen products firmed last week on renewed demand from India, while traders wait for news on whether European plants could switch back on line, at least a little. Potash and phosphates had a weaker tone, though all nutrient costs are elevated. Politics, economics, and weather will all play a role in how these markets play out.

As with grains, nothing is certain but uncertainty.

Knorr writes from Chicago, Ill. Email him at [email protected]

The opinions of the author are not necessarily those of Farm Futures or Farm Progress.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like