December 8, 2023

Despite a global economy that’s showing signs of toughness and making progress in tackling high prices, the International Monetary Fund’s October 2023 Global Economic Outlook shows bumpy roads are ahead.

Recovery from the pandemic’s ripple effects, the conflict in Ukraine and the growing divide in global trade will be like combining downed corn — slow and tough, especially for countries still developing their economies.

The world’s economic growth is expected to dip from a decent 3.5% in 2022 to just 3% in 2023, and even a bit lower to 2.9% in 2024, which is not as good as the usual 3.8% we saw from 2000 to 2019. The big economies, including ours, might see a slowdown, despite the U.S. doing a bit better than expected. However, Europe’s slower growth and issues like China’s housing market troubles are like pests in the field, affecting everyone.

Looking at the next few years, that means the global economy isn’t expected to grow as strong as we’d hope, making it harder for countries to improve living standards. And while prices might start to ease up, they’re still expected to be higher than what we’d like until at least 2025.

With all this uncertainty, is now the right time to buy farmland?

In my lifetime, farmland values have risen and fallen and risen again. Prices may continue to rise even higher than they are now, or they could retreat. The two fundamental questions we need to ask ourselves are: Is farmland a good investment? And what are the current fundamental drivers of farmland value?

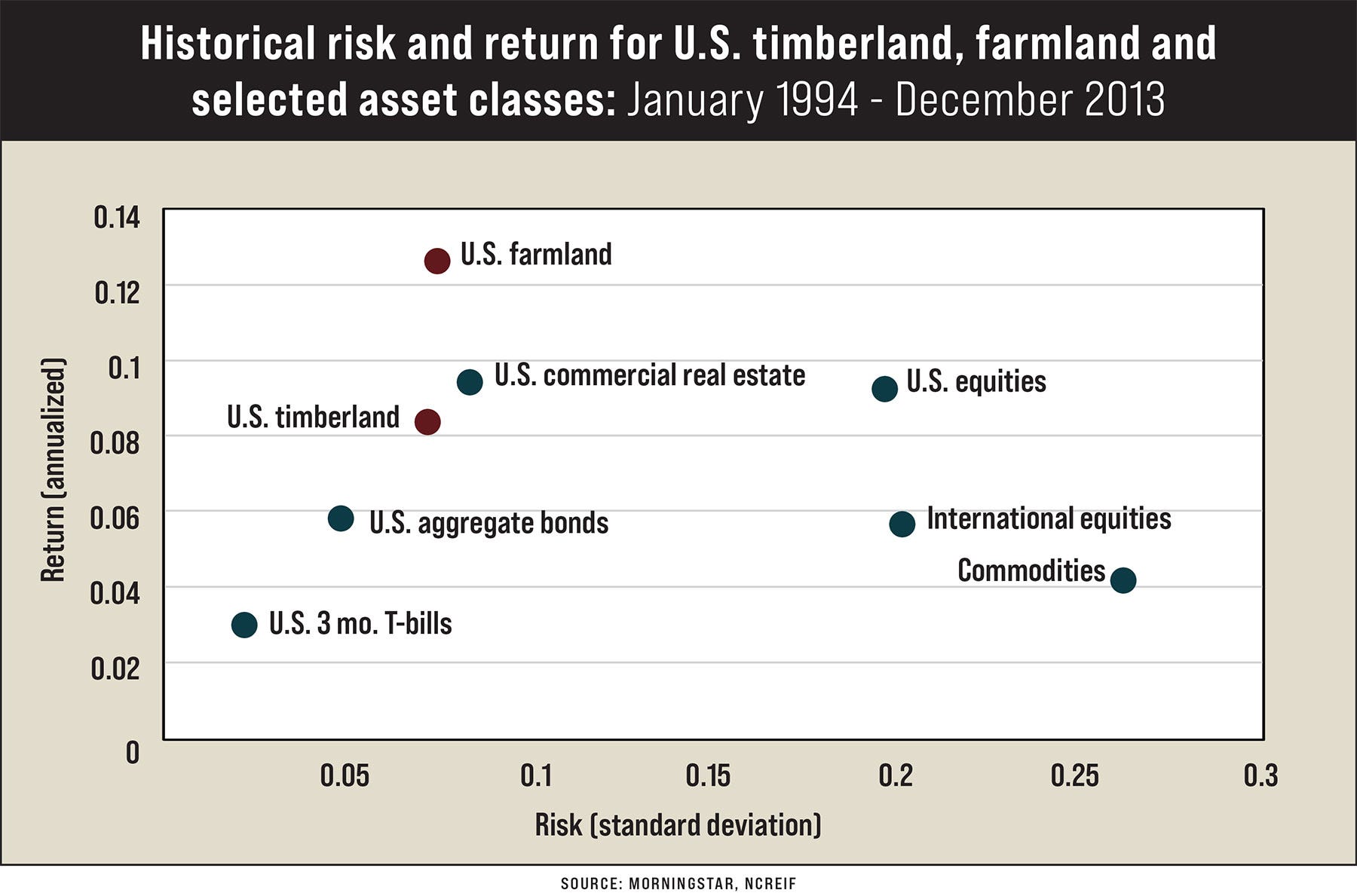

Farmland has been a good investment. In the University of Illinois farmland index, we find that every $100 invested in farmland in 1979 is worth over $500 today. Research also indicates that farmland investments have produced the best returns at the lowest risk over the last 30 years.

But will farmland continue to be a good investment? Let’s look at some of the economic forces that drive farmland value today.

Food vs. fuel

In the past decade, the agricultural sector has witnessed a significant rise in commodity prices, a trend primarily driven by the implementation of the Renewable Fuel Standard and the escalating demand for ethanol and biofuels with low greenhouse gas emissions. This surge in demand for biofuels has created a unique intersection between energy policies and agricultural practices, profoundly influencing the market dynamics for key crops.

Recent headlines tout the airline industry’s interest in ethanol to power air travel as it seeks to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions footprint. And while the popularity of electric vehicles continues to grow, concerns about an overtaxed electrical grid, range of mobility and end-of-vehicle-life economics indicate that gasoline- and ethanol-fueled vehicles will be around for a while longer.

Land values are intrinsically linked to the profitability of the crops they support, meaning any major shift in crop demand due to energy policies could lead to corresponding changes in land values. The intersection of food, fuel and future uses presents both challenges and opportunities for the agricultural sector.

Global farmland dynamics

As populations grow and standards of living rise, particularly in developing countries, the demand for a more varied and calorie-rich diet increases. This surge in caloric demand is pushing the agricultural sector to expand its production capabilities. New areas, previously untapped due to technological or economic constraints, are now being brought under cultivation.

Issues of food security, environmental sustainability and even geopolitical relations will increasingly influence farmland economics as countries navigate the complex interplay of feeding their populations, protecting their agricultural sectors and engaging in global trade.

Farmland securitization

In the realm of investment and asset management, farmland has historically stood out as a significant yet underutilized asset class, primarily due to the lack of an effective securitization mechanism. Securitization — the process of converting an asset into a marketable security — can unlock the latent potential of farmland, offering a pathway to more efficient ownership and operation. This gap in the financial structuring of farmland assets represented a missed opportunity for both the agricultural and investment communities.

Direct ownership is the primary method of investment in farmland, which, while straightforward, comes with its own set of challenges, including high entry costs, management complexities and liquidity issues.

Recent entries of institutional investors representing retirees and individual investors, farmland REITS (real estate investment trusts) and crowd-sourced funding participants of farmland ownership have opened the marketplace to people who would not have been able to participate otherwise. Their investment dollars are now in farmland, and this trend will only continue.

Investors now can use these assets to hedge against market volatility in other sectors. The unique characteristics of farmland as an investment — such as its low correlation with traditional asset classes like stocks and bonds — make it an excellent tool for portfolio diversification.

In my career, I have purchased many farms for clients. No one can definitively say that farmland prices will continue to go up or whether they will go down. What we can say is that farmland has been a good investment, and there are strong economic forces that indicate it will continue to be a good investment going forward in the long run.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like