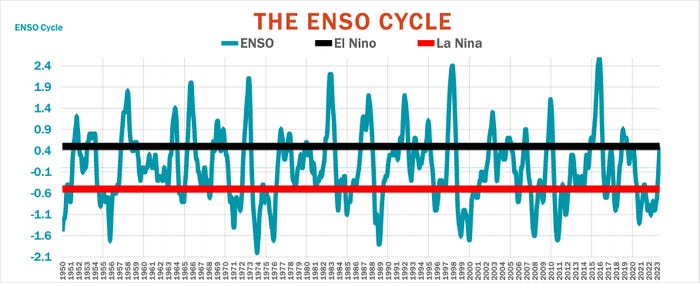

Even if you don’t speak Spanish, two words from today’s headlines are easy to recognize: El Niño.

Farmers follow this weather phenomenon routinely due to its impact on crop yields. Now, thanks to a sizzling summer across the globe and worries about climate change, the rest of the world is hearing plenty about ocean temperatures and atmospheric currents too.

As with most things, the news generated plenty of fear along with the facts. “The era of global warming has ended,” António Guterres, UN Secretary-General, said last week. “The era of global boiling has arrived.”

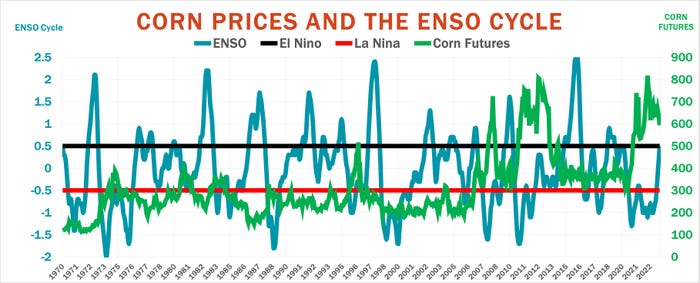

July appears on track to be the warmest month on record, but history suggests not automatically blaming El Niño if world food prices shoot higher this year.

To be sure, rising temperatures in the equatorial Pacific and a shift in the trade winds further south increase potential for drought in some countries around the world, especially in Southeast Asia, Australia and parts of Europe. But this can also bring better yields in the U.S. and South America, where crop production is expanding. As a result, El Niño is actually associated with lower world food prices statistically.

Still, as the 2023 growing season illustrates, this doesn’t mean summer can’t bring trouble for Midwest crops. June was one of the driest on record in key growing areas following official announcement that another El Niño was underway.

Why should you care? Here’s what the data says – and doesn’t say – about El Niño’s impact on markets.

No silver bullet

First off, the El Niño connection isn’t black or white. It’s gray, and sometimes a fairly light shade. Wheat production in Australia has one of the strongest correlations, and it’s modest, accounting for around 30% of the variance with yields over the past 80 years. Wheat fields down under during the southern hemisphere winter are actually in better than average shape according to the latest Vegetation Health Index, though long-term forecasts expect below average rainfall and above average temperatures to emerge from August to October.

Crops in Europe are already stressed from a long, hot summer that sparked downgrades to production from Scandinavia down through Germany to Romania and the Balkans. But the biggest driver of food insecurity at the moment comes from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – and El Niño can’t take the blame for that.

Indeed, both the timing and impact of these events are variable. El Niño means “the Child” and is typically present around Christmas. Above normal sea temperatures typically last around a year. The last El Niño in 2018-2019 was around for only 10 months and was fairly weak. The 2014-2016 event covered 17 months and was the strongest on record. Yet Australian wheat yields held up in during the longer, stronger event while suffering more in the weaker, shorter one.

Palm oil threat

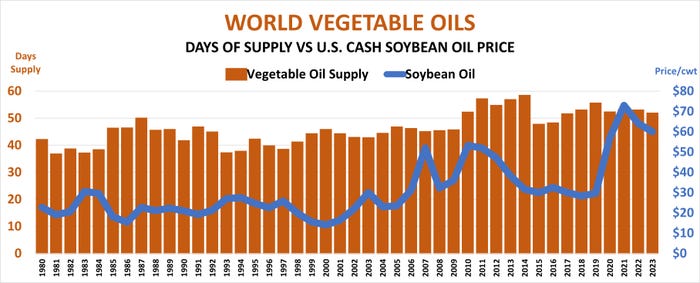

The 2014-2016 El Niño did cut palm oil yields in Indonesia and Malaysia, which account for a third of the world’s total vegetable oil production. The rally that followed was fairly modest, thanks to good soybean production in the U.S. and South America that offset the losses. U.S. cash soybean oil prices show only a weak and non-statically significant correlation to world vegetable oil days of supply, and USDA projects just a modest tightening of inventories in the year ahead.

Local factors also cloud forecasts for impacts from the new El Niño on palm oil. Production in Indonesia held up fairly well in the two previous events because of expanding acreage and newer plantations. Yields in Malaysia, by contrast, are in long-term decline due to aging plantations, which could exacerbate losses though it produces just 40% of Indonesia’s total.

Dry weather isn’t all bad for crops, either. Untimely rains can disrupt harvest, especially in palm plantations, where trees are picked year-round. That’s why production can suffer sometimes during La Niña events, which tend to be wetter than normal in Southeast Asia.

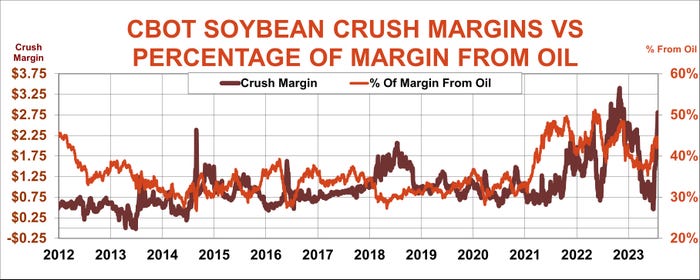

El Niño concerns may also be getting baked into prices as traders “buy the rumor.” Soybean oil futures led the June-July soy complex rally on the board, though hopes for a biodiesel boom and U.S. weather also factored into gains after a disastrous crop in Argentina, the world’s leading exporter of products.

The fate of the crop here in the U.S. remains in the balance. Despite a shift cooler and in some places wetter in July, the percentage of both crops in drought increased last week, even though El Niño summers are associated with better corn and soybean yields in the U.S.

Cycle shift

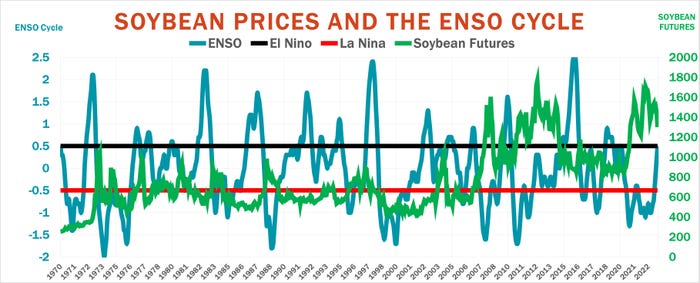

Corn and soybean futures follow the El Niño/Southern Oscillation cycle – the formal name for these patterns. El Niño tends to bring lower prices, with rallies more likely in La Niña years. But correlations, while statistically significant and not resulting from mere chance, are fairly weak, suggesting just a 35% probability of decent yields and lower prices.

The big shift in acreage from soybeans to corn this spring in the U.S. could be just as important as weather as summer ends. Other factors bear watching, too.

The U.S. dollar is more than 10% off its highs from last fall, despite another interest rate increase last week by the Federal Reserve. Betting on Federal Funds Futures indicates traders believe the central bank will begin cutting rates in in the first quarter of 2024, weakening the greenback because currencies generally follow rates.

Currency prices don’t directly impact U.S. grain exports, but they can inflate or deflate commodity prices. So, a weaker dollar tends to boost prices if demand holds up.

Exports likely will be the swing factor for both corn and soybeans in the year ahead. Importers tend to buy more if their economies are booming or they face a shortfall in their own production.

Fallout from financial markets could also be in play. The International Monetary Fund last week said inflation remains a risk. It noted: “Central banks may keep interest rates higher for longer than currently priced; given investors’ benign inflation outlook and growing expectations for a soft landing, this could increase financial stability risks and weigh on growth.”

The stock market reacted on cue, posting a new high for the year before reversing lower after momentum indicators stalled.

As for the grain trade, November soybean futures remain in a sharp uptrend but showed signs of chart weakness last week while testing support on Friday. December failed to hold support at several trendlines amid a bearish moving average crossover signal.

Both crops remain profitable for growers with average yields and costs headed into USDA’s August 11 key World Agricultural Supply And Demand Estimates, so calibrate your tolerance for risk of bearish surprises.

Knorr writes from Chicago, Ill. Email him at [email protected].

The opinions of the author are not necessarily those of Farm Futures or Farm Progress.

Read more about:

WeatherAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like