Welcome to winter – though for many of us, it seems like winter started early this year. The markets are largely trading on South American weather forecasts early in the new year, which I dove deep into in last month’s column. But there are still other important weather factors to consider on the home front as farmers look towards 2024 production goals.

This winter, U.S. corn and soybean farmers will be closely watching an El Niño event unfold across the country. Coming off several consecutive La Niña events prior to this winter, farmers will have to be mindful of how the opposite weather patterns could impact not just 2024 winter crop development, but potentially early conditions for 2024 spring crops as well.

Through November 2023, the National Weather Service’s Climate Prediction Center expects that El Niño pressures will persist across the Northern Hemisphere through the remainder of winter, with a 62% chance that El Niño will last through April – June 2024. El Niño events typically reach their peak severity during October through February.

An El Niño winter

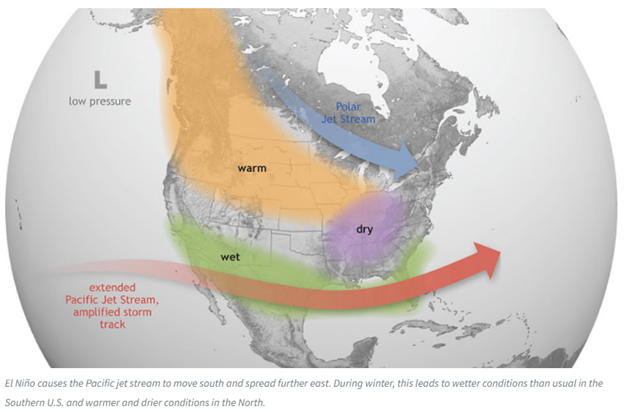

What does an El Niño winter mean for U.S. corn and soybean producers? It will depend on the part of the country in which you reside. The Upper Midwest and Plains are likely to experience warmer than average winter temperatures. The Eastern Corn Belt could see a dryer than normal winter while more moisture is anticipated for the Southern U.S. border.

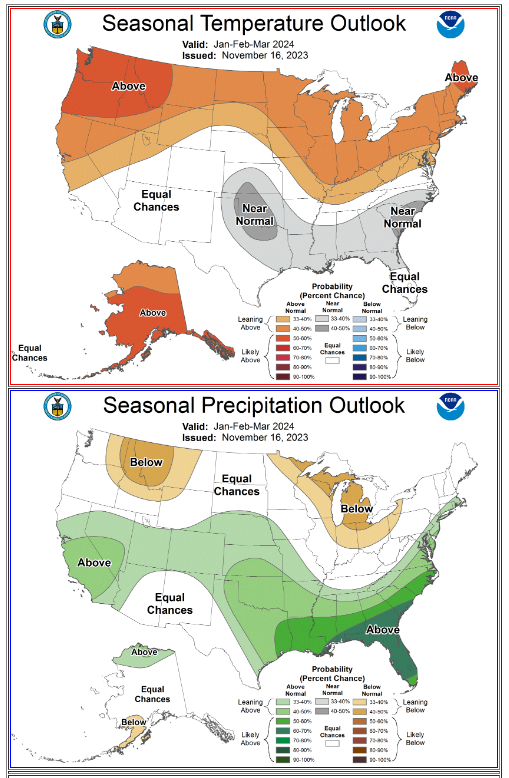

NOAA’s three-month outlook, last updated in mid-November 2023, shows high chances of this trend occurring early in 2024. During the first three months of 2024, the upper half of the continental U.S. will experience high chances of above average temperatures, while elsewhere in the country will have equal chances for normal temperatures for that time of year.

Moisture outlooks between January and March 2024 are consistent with La Niña patterns as of late November 2023, with above average chances for moisture forecast along the Southern Rim. The Southern and Central Plains will also enjoy above average precipitation outlooks during that time.

While winter precipitation chances are holding near seasonal averages for the Upper Midwest during the first three months of 2024, much of the Eastern Corn Belt – especially Michigan, Wisconsin, Indiana, and Ohio – will see below normal levels of precipitation during that time.

Production risks

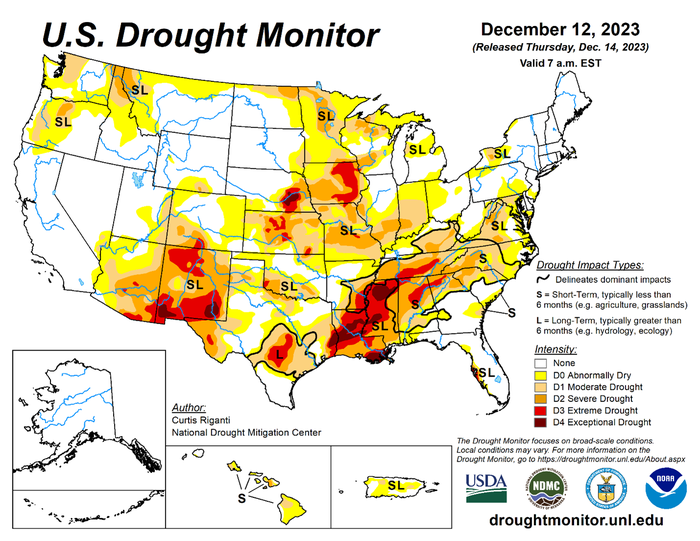

Through mid-December, 44% of U.S. corn production and 48% of soybean production was in an area experiencing some sort of abnormally dry to exceptional drought conditions. While El Niño pressures could help to pull the Eastern Plains and Southern Mississippi River Delta out of chronically dry weather, the Eastern Corn Belt could be at risk.

Through November, soil moisture levels in the Eastern Corn Belt were trending 0.2cm – 1.0cm below the prior month. Soil moisture levels tend to start recharging during that time, so even though the Eastern Corn Belt has largely avoided severe drought ratings through the end of 2023, it is starting to fall behind the curve in terms of soil moisture recharging for this time of year.

It’s also worth noting that every month since this past June, monthly soil moisture levels have recorded the lowest values in a five-year period, intensifying the risk of a potential drought in the Eastern Corn Belt ahead of 2024 planting.

Could dry soils also lead to nitrogen loss in the coming months? It remains a risk, but if it occurred, it likely already happened at fall application. Water is essential to turn ammonia into ammonium, but it’s actually held in the soil through bonds with clay and organic matter. Anhydrous ammonia doesn’t necessarily bind to water in the soil, rather it binds to the soil because of positive and negative charges.

So if soils are dry and cloddy instead of moisturized and more evenly distributed, there is a higher chance for nitrogen loss following fall applications if it seeps between soil pores before bonding. For growers anticipating spring nitrogen applications, pay close attention to proper injection depth and good soil coverage to limit nitrogen losses.

Murky yield history

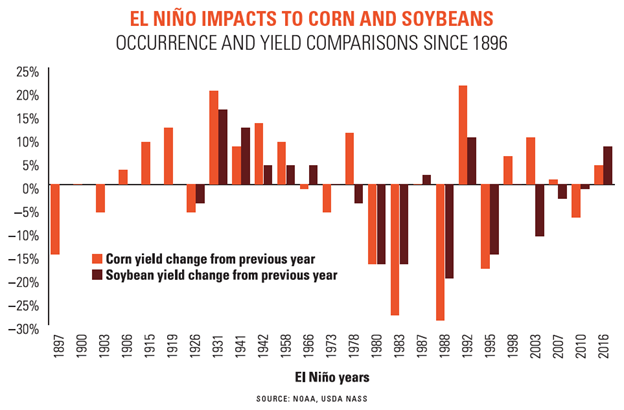

There have been 25 growing seasons since 1896 in which NOAA has recorded El Niño activity. In 15 of those events, corn yields increased an average of 9% from the previous year. In the remaining 10 years of yield decreases, annual yields dropped by an average of 13%.

Soybean yield data does not go back as far as its corn counterpart, with only 19 years recorded, and the results are narrower for soybean yields. Soybean yields have risen eight times in El Niño years since 1924 by an average of 8% and decreased nine times by an annual average of 10% from the previous growing season. There were two El Niño events in which soybean yields were unchanged from the prior year.

For farmers, this historic activity indicates that there is slightly more downside risk to yields in El Niño years for soybeans. And while history favors larger corn yields, it’s a slim margin. And for both crops, when yields go lower in El Niño years, they drop by a larger margin than in El Niño years that produce higher yields.

But there isn’t a lot of data that provides firm certainty to predict how El Niño weather patterns will shape corn and soybean yields. This will complicate farmers’ forecasting abilities in 2024 – especially those in the Eastern Corn Belt.

Marketing and profit implications

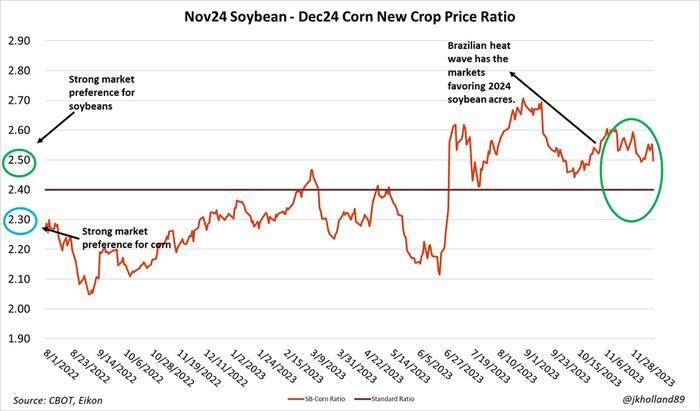

As of late November 2023, markets were increasingly enthusiastic about supporting a soybean acreage expansion in 2024, especially as weather worries grew surrounding Brazil’s soybean crop. U.S. soybean supplies are expected to end the 2023/24 marketing year as the 12th tightest on record, just marginally behind 2020/21 levels.

On the other hand, domestic corn stocks are expected to balloon to their largest level since the 2018/19 marketing year that was underscored by the trade war with China.

Historically, El Niño years offer slightly more optimism to corn than soybean production, though we know that there is still a lot of uncertainty surrounding yield – and therefore marketing – prospects. If corn acres go lower but yields go up, then supply levels should remain relatively comfortable into the 2024/25 marketing season.

Higher soybean acres could offset potential yield decreases for the 2024 soybean crop in an El Niño year. But the 2024 soybean will need to hit new highs this summer to adequately supply the growing domestic and global demand for U.S. soybeans.

Farmers in the Eastern Corn Belt may also need to re-evaluate their nutrient management strategies ahead of planting if dry soils persist throughout the winter. Through late November, per acre costs for anhydrous ammonia were far more competitive than liquid nitrogen and urea counterparts though those values could shift depending on how much nitrogen soils could lose at an individual field level.

Farmers should work with their crop advisors to review their agronomy and nutrient plans to ensure corn and soybean crops have access to nutrients when, how, and where they need it for the upcoming 2024 growing season.

Read more about:

WeatherAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like